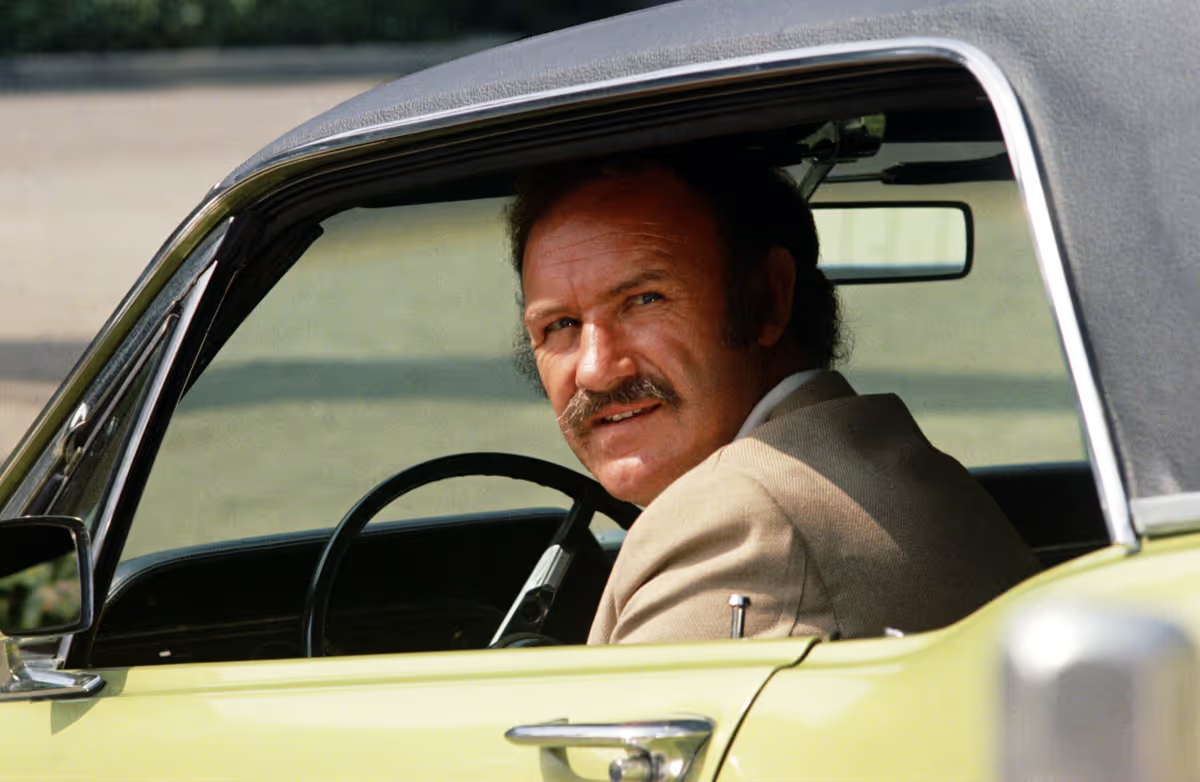

“I Didn’t Solve Anything”: With ‘Night Moves,’ Gene Hackman Found the Dark Heart of the 1970s

For director Arthur Penn, Hackman played a private eye troubled by darkness both around and within him.

This week The Reveal pays tribute to Gene Hackman, who we recently lost at the age of 95.

Private eye Harry Moseby’s past casts a long shadow over the 1975 mystery Night Moves, even though we never learn much about it. We hear about the parents who abandoned him and that he eventually tracked down at least one of them. We learn about his time in the NFL playing for the Raiders. He was good enough to earn a Pro Bowl spot at least once, but only a few of the characters he encounters know his face or name. The details we do get say a lot, however. Asked where he was when Kennedy was shot, Harry provides telegraphic answers for his whereabouts during both the JFK and RFK assassinations. “When the president got shot,” he tells his interrogator, “I was on my way to San Diego. Football game. When Bobby got shot, I was sitting in a car, waiting for a guy to come out of a house with his girlfriend. Working on a divorce case. One of those times I wish I was in another business.”

Somewhere in that five-year gap, Harry lost an identity with a clear sense of purpose and picked up one that sent him into the shadows, far from the glories of the gridiron. Harry has strewn relics from his past throughout his cluttered office, but they belong to another time, maybe even another America. He’s a good enough detective to stay in business and to have to turn down job offers from a larger firm, but nothing about the way he lives suggests he’s thriving professionally. He gets by, but Harry carries himself like a man doing a job that gives him no pleasure working in a grimier, more dispiriting country than the one in which he’d expected to live. The events of those five years between slain Kennedys never really gets filled in, but the movie never really needs to explain them. They’re the years when everything went wrong. It’s a Boomer cliché that history went off the rails with John F. Kennedy’s death, but Night Moves gives that cliché substance, depicting Harry as a fallen man in a fallen world a little more than a decade out from Dallas. His particular curse is to feel the weight of sin more heavily than those around him.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

On an audio commentary recorded for Night Moves’ Criterion Collection edition (set to be released March 25th), film scholar Matthew Asprey Gear, author of Moseby Confidential: Arthur Penn’s Night Moves and the Rise of Neo-Noir, describes the film as a product of clashing sensibilities built around this question: “What kind of protagonist was Harry Moseby going to be?” For screenwriter Alan Sharp, he was an appropriately grim, hopeless protagonist at the center of what Gear describes as a “fatalistically hopeless noir.” Director Arthur Penn didn’t want to plunge Moseby all the way into despair. These seem like irresolvable positions, and they might have been if anyone but Gene Hackman, an actor with an innate gift for playing characters with irresolvable contradictions, took the part.

Night Moves opens with Harry taking on a case and ends with him pursuing the case to its bitter end, long after anyone has stopped paying him to do the job. It’s a twist on a familiar story: a mother looking for her wayward daughter. Here the mother is Arlene Iverson (Janet Ward), a former starlet who married into money but now depends on her daughter Delly’s (Melanie Griffith) trust fund to keep up her comfortable lifestyle. But the free-spirited Delly has disappeared and searching for her will take Harry first to a film set in New Mexico then to the Florida Keys, a path littered with shady characters. Meanwhile, Harry’s own life begins to unravel. After trailing his wife Ellen (Susan Clark) to a movie theater, he discovers she’s having an affair.

The film concludes — and this is a spoiler — with neither element fully resolved. After taking a winding path to Delly, Harry has to retrace his steps to investigate a subsequent crime. He’s seen off at the airport by Ellen, with whom he’s reached a kind of detente that might lead to a full reconciliation when he returns. Or if he returns: Harry ends the film literally going in circles, injured and unable to control a boat on which he’s the sole surviving passenger. He might summon the will to grab the wheel or he might bleed out in the middle of the ocean. It’s neither a definitively bleak nor particularly hopeful ending.

It also feels like the only possible note on which Hackman’s performance could conclude. Harry can swing into action when necessary, but he’s at heart a weary, wounded man. When he confronts Ellen’s lover Marty (Harris Yullin) in Marty’s home, Harry wears his fury as a mask for his sadness and confusion. “Come on, take a swing at me Harry, the way Sam Spade would,” Marty tells him. But Harry knows he’s not that kind of private eye hero and that taking a swing will only make matters worse. It’s doubtful that Marty even takes the threat seriously in the moment. Ellen, it seems, can’t stop talking about how sensitive her husband is.

Harry shows up at Marty’s apartment wearing a threatening grin but both the threats and grin crumple when he asks the question that’s brought him here: “How serious is it?” But he’s asking the wrong person. Marty can’t tell him. Maybe Ellen can, but Harry can’t or won’t ask her directly. Harry doesn’t know how he got to this point and if there’s a way out, it’s one that he’s not willing to take. He can follow clues and unravel crimes, but this more intimate sort of mystery is beyond his faculties to untangle. Instead he lives in doubt and misery.

Hackman plays Harry as a man never willing to fully be himself except, maybe, in solitude. In one the film’s most famous exchanges, he turns down the offer to accompany Ellen to the movie she attends with her lover, Eric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s, because he “saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry.” As others have pointed out, that’s not quite the insult it seems. Penn was famously a fan of the French New Wave and a professed admirer of Rohmer’s and there’s more than a little overlap between Rohmer’s film and Penn’s.

For starters, there’s an obvious narrative echo, albeit one that plays out differently in each film. My Night at Maud’s protagonist spends the night alone with a beautiful woman and engages in an intense conversation with a woman he’s only recently met but refuses to have sex with her on moral principle. In Night Moves, Harry finds himself in a similar situation with Paula (Jennifer Warren), who’s living with Delly and Delly’s stepfather in Florida, but gives into temptation. Yet both movies ultimately concern the impossibility of escaping regret, whether it’s a pleasure declined or one taken. A student of chess, Harry likes to replay old games, including a 1922 match in which one player famously missed a chance to win via a queen sacrifice and a pair of knight moves. “Must have regretted it every day of his life,” Harry says. “I know I would have.”

Hackman makes it clear that Harry knows this sort of regret, and for situations more consequential than a chess game. We learn about one such instance when Harry tells Ellen of tracking down his father and ultimately doing nothing. That he tells Ellen this story at all suggests maybe there’s a way forward for their marriage. But Hackman plays the scene as such an effort for Harry, it’s possible that this is as far as the marriage can go and he’ll have to live with that regret, too. Harry’s an unsure man living in an era of uncertainty. When he returns to Florida to resolve the unfinished business opened by his search for Delly, he tells Paula, “I didn’t solve anything. Just fell in on top of me.” That line, and Hackman’s delivery, provides the ultimate answer to the question of what kind of protagonist Harry Moseby is. He’s a man who things fall in on top of, be they crime, heartbreak, or history, and one who understands he might not be able to crawl out from beneath them again.

Discussion