Shakespeare’s Son, Frankenstein’s Monster, and Life After Death: Notes from the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival

The Reveal reports back from this year's Toronto International Film Festival.

This past Sunday afternoon, I boarded the 501 streetcar that serves Toronto’s Queen Street, took a 40-minute ride to the beach, and watched the afternoon fade into evening at the end of a lovely day. If you’re ever in Toronto, I can’t recommend this highly enough (and I’m sure any Torontonian reading this would agree). And though I’m sure it’s a pleasant way to spend any sunny day, I used it to provide a much-needed reminder that there’s more to life than movies. It’s easy to forget that in Toronto this time of year. And, at its best, the Toronto International Film Festival makes it hard to wish for anything more.

For years I experienced TIFF secondhand, hearing from others about all the exciting (and some not-so-exciting) movies that play each year, and of other wonders, like Toronto’s excellent noodle restaurants and the frequently out-of-service escalator at the Scotiabank Theatre. This year, I seized on the chance to experience TIFF for myself. And now I can tell you about what I saw (and report that the Scotiabank escalator has remained fully functional throughout TIFF as I write this).

I’ll have taken in something like two dozen movies during my time here, which means there are many more that I did not get to. (It’s a big fest.) If this year’s offerings have had an overarching narrative, I missed it (or maybe it will only become clear later). But a few themes and connections emerged. Below you’ll find a few on-the-ground notes on the 50th TIFF that will hopefully double as a preview of what to look out for in the weeks to come, and maybe a bit further out given that some films still await distributors. (And since I’ve still got a few movies to watch before I leave, including some big titles, I’ll drop some additional thoughts in the comments section today and tomorrow.)

Past Lives (or The Linklater Biopic Sandwich)

Should it be possible to use words like “sweet” and “cute” to describe a film about Jean-Luc Godard and the making of Breathless? Unlikely as that may sound, Nouvelle Vague, one of two new Richard Linklater films to play the festival, answers the question in the affirmative. The film’s light-as-a-fresh-baked-croissant approach might limit its ability to offer insights into cinema history, but doesn’t stop it from being a frequently delightful behind-the-scenes story starring Guillaume Marbeck as a gnomic, insolent Godard caricature, Zoey Deutch as a skeptical but largely game Jean Seberg, and a cast of dozens playing seemingly everyone involved in the launch of the French New Wave or just in the general vicinity at the time. (Composed shots with titles identify the players, famous and otherwise.) Though it lacks the New Wave’s revolutionary spirit, Linklater’s film flawlessly mimics the look and feel of a moment when anything and everything suddenly seemed possible.

By contrast, there’s scarcely a light moment to be found in the story of another groundbreaker, Christy, a David Michod-directed biopic about Christy Salters (neé Martin), whose ‘90s success helped popularize women’s boxing. Unknown at the time: Salters was trapped in an abusive relationship with her husband/manager James Martin. Sydney Sweeney stars as Salters, delivering a performance that can rightly be called transformative because a) she initially seems unrecognizable and b) she makes it easy to forget you’ve ever seen her in anything else. Sweeney’s good, whether capturing Salters’ surprise and joy after unexpectedly winning a West Virginia Toughman contest or transforming herself into a heel for the sake of publicity, a public persona that included the liberal use of homophobic slurs that temporarily helped hide her other secret. The movie’s just okay, however, weakened by villains who reveal themselves as odious shits the moment they first appear onscreen, namely Ben Foster as Martin and Meritt Wever as Salters’ conservative mom.

Linklater’s other film to play TIFF offers an even thinner slice of a famous life than Nouvelle Vague but delves deeper into the psychology of its witty, troubled protagonist. Unfolding over the course of a single night and set almost entirely in one location, Blue Moon stars Ethan Hawke as songwriter Lorenz Hart, who spends a busy night hanging out in Sardi’s. Though deserted as Hart arrives, the venue will soon play host to a crowd gathered to celebrate the premiere of Oklahoma!, the first product of a new partnership between Hart’s past (and possibly future) collaborator Richard Rodgers (Andrew Scott) and Oscar Hammerstein (Simon Delaney). To pass the time, Hart regales Sardi’s bartender Eddie (Bobby Cannavale) and anyone else who will listen about Elizabeth Weiland (Margaret Qualley), a talented, beautiful college student. But the more he talks about his infatuation as he tries not to drink the shot of bourbon he’s asked Eddie to place on the bar, the clearer it becomes how troubled he is by his old partner’s success. Hawke’s even harder to recognize than Sydney as the diminutive, balding Hart, but he’s thoroughly convincing as a man whose insightfulness and ability to turn a phrase has done little to ease his way in the world.

Coincidence or trend?: Basement Dwellers

This year’s TIFF saw the premiere of two movies featuring characters chained in basements (unless there were more I missed). The Man in My Basement, a horror-ish adaptation of Walter Mosley’s novel of the same name, directed by Nadia Latif, is packed with style and ideas tied to the history of Sag Harbor Hills, a Black community on Long Island with a history dating back to the whaling era, but only really comes to life in a handful of Silence of the Lambs-like interrogation scenes between stars Corey Hawkins and Willem Dafoe. The slight but more successful Bad Apples stars Saoirse Ronan as a primary school teacher in provincial Britain whose efforts continually get disrupted by one out-of-control student. Then, by chance, she happens upon a solution to the problem child. (See above for a hint.) The Jonatan Etzler-directed film never cuts as deep as Election, an obvious model, but Ronan’s performance makes it worth a look.

Coincidence or Trend?: The Play’s the Thing

Though two of the best films of the fest—and two of the best I’ve seen this year—don’t otherwise have that much in common, both ultimately concern art’s ability to express what’s otherwise impossible to say. Joachim Trier’s follow-up to The Worst Person in the World, Sentimental Value tells another Oslo story, albeit one largely confined to one corner of the city: an inviting Victorian that’s been home to several generations of the same family. But, as the film opens, it looks like that time might come to an end. After the death of their mother, Nora (Renate Reinsve, excellent again), a stage and TV actress of some renown, and her sister Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, in what should be a breakout performance) reluctantly wait to learn what their father Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård) plans to do with the place. Gustav’s an internationally acclaimed director who now finds it easier to be honored at retrospectives than to secure financing for new films. They expect him to sell it. Instead, Gustac wants to use it as a location for a semiautobiographical movie starring Nora. That Nora’s rejection of the plan leads Gustav to recruit Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), an American star who’s grown enamored with his work, is just the first unexpected turn in a moving but thorny exploration of how patterns repeat across generations and how some questions can’t be answered with mere words.

An adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, Hamnet takes its name from the son William Shakespeare lost to illness shortly before writing the famous play (sort of, maybe) named after him. But the film is much more than a feature-length answer to a trivia question. Unhurried and careful with details, director Chloe Zhao (who co-wrote the script with O’Farrell) opens with the courtship of Will (Paul Mescal), a restless, well-educated glover’s son and Agnes (Jessie Buckley), the daughter of a local landowner who’s held true to the some of the pagan traditions of her mother, a woman of the woods. While Will finds success and fame in London, Zhao’s focus largely remains trained on Stratford-upon-Avon and the family he’s reluctantly left behind. It’s a film of big dramatic moments but also small gestures, all beautifully played by Mescal and Buckley as characters who love but don’t always understand one another, even before being forced to reckon with an unthinkable loss.

Made for these Times

All movies are products of the eras in which they’re created, but some comment on this more directly than others. Jafar Panahi’s first film since his release from prison following a 2022 arrest (only the latest in a long series of run-ins with the Iranian regime), the Palme D’Or-winning It Was Just an Accident is yet another powerful act of defiance folded into a gripping (and often unexpectedly funny) film. While driving on a dark road, a family of three experiences mechanical issues after hitting a stray dog. This sets in motion a chain of events that will lead to the father’s kidnapping by an expanding assortment of former political prisoners who believe him to be “Peg Leg,” a feared guard who tortured them. Except they’re not sure, which leads to a lot of driving around and arguing as they attempt to settle on a plan of action when—or more accurately, if—they can determine his true identity. Panahi never lets viewers forget the brutality at the heart of the story but spends just as much time revealing the humanity of angry characters stuck in a dehumanizing system. They want revenge, but what they need is a way out.

Though set in 1977, Gus Van Sant’s Dead Man’s Wire depicts pressing contemporary issues in nascent form via the true story of Tony Kiritsis (Bill Skarsgård), an Indianapolis man who opts to deal with a mortgage company he believes to be cheating him by kidnapping one of its executives (Dacre Montgomery). Dead Man’s Wire touches on everything from the widening gulf between haves and have-nots to the media’s role in shaping the news it covers. Unfortunately, the film only touches on such issues without really developing, but it’s skillfully made and a fine showcase for Skarsgård’s unnerving charisma and unsettling energy.

No Other Choice, the latest from Park Chan-wook, takes on the dehumanizing aspects of How We Live Now much more directly. Park immediately establishes a tone of high irony with an opening scene of domestic bliss so perfect—even the dogs could be catalog models—that it’s obviously doomed to fall apart. And it does. Quickly. Deemed unnecessary by the new owners of the paper company where he’s worked for years, learning the trade from experts, You Man-soo (Lee Byung-hun) finds himself jobless and without a clear sense of who he even is without his old job. When economic woes make selling the childhood home he’d worked for years to reacquire, he considers a new identity: murderer. A second adaption of Donald Westlake’s The Ax (Costa-Gavras previously adapted it in 2005), No Other Choice is both funny and timely, tailor-made for a moment in which humanity seems to be outsourcing every imaginable job to systems and machines of our own creation that now seemed destined to take our place. Park occasionally plays it a little too loose, letting the pace slacken in the middle, but the barbs remain sharp, the set pieces remarkable, and the cast locks into the darkly funny mood of the piece from the first shot.

Outside of Society

I’ve wanted to see Clint Bentley’s exquisitely melancholy Train Dreams on the big screen since watching it at home while covering Sundance, especially after learning it would primarily play on Netflix. I was not disappointed when the chance arrived and, in its story of Robert (Joel Edgerton), a man who lives a largely solitary existence in the American Northwest as sweeping changes transform the country, I heard faint echoes of another Netflix-bound film about a life on the fringes I saw earlier in the day. (This might just only the illusion of a connection created by proximity, but indulge me.) Guillermo del Toro’s adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein makes some bold choices in the ways it alters the source material. Not all of them work, but the film is as locked into the cultural upheaval of Shelley’s age as any cinematic treatment and, thanks to Jacob Elordi, features one of the most sympathetic treatments of the Monster of any version. (The addition of a bottomless wealthy man in pursuit of immortality, played by Christoph Waltz, feels quite contemporary, however.) That it’s filled with searing, beautiful images almost goes without saying. It’s a Del Toro film. See it on the biggest screen you can while you can (if you can).

A remote farm in the north of Germany serves as the single setting of Sound of Falling, an expansive, circular drama from writer-director Mascha Schilinski that flits across the timeline to depict the experiences of four girls from the early years of the 20th century to the early years of the 21st. Three of them belong to the same family. All experience death-haunted variations of family secrets and misplaced sexual attraction, most often depicted from the perspectives of those peering into rooms or gazing out windows to see what they’re not supposed to see as history unfolds at a great distance while managing to touch them anyway. The visually striking film gets more upsetting as it goes along, when oblique details start to come into focus and it becomes obvious that even those not necessarily doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past find ways to create their own variations of it. Though operating on a much more modest scale, Sophy Romvari’s Blue Heron proves just as gutting, telling a semi-autobiographical story of growing up with a troubled older brother that begins as a series of hazily remembered memories then changes shape in the late stretches with devastating effect.

Good Stuff and Quick Hits

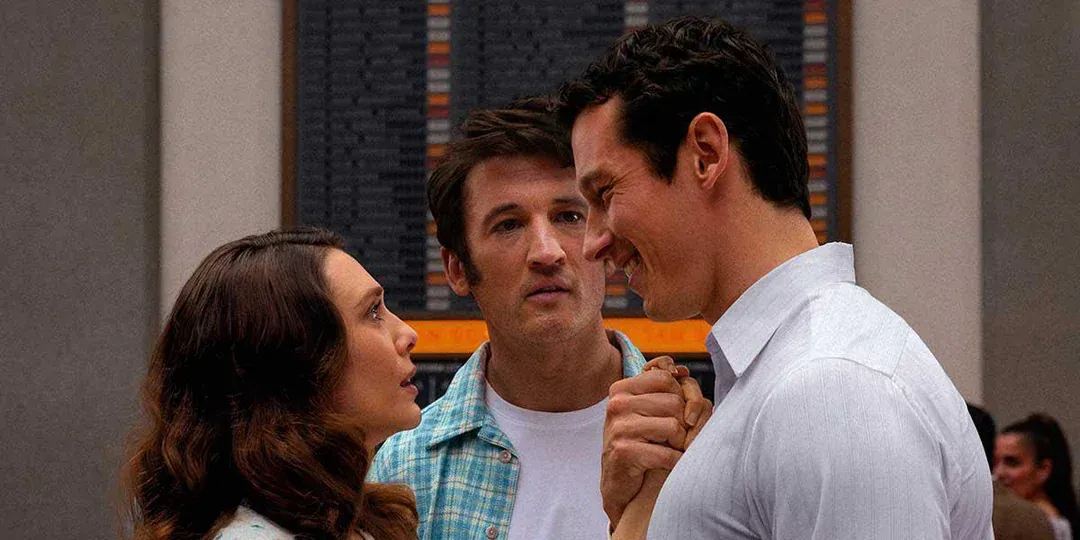

A charming, sometimes thought-provoking comedy, David Freyne’s Eternity is largely set in a convention center where the newly deceased must decide on the afterlife in which they’d like to experience forever. It’s a tough choice, even when choosing doesn’t involve picking between two great loves, as Elizabeth Olsen’s character discovers when she’s compelled to select between the husband she lost in the Korean War (Callum Turner) and the man with whom she’s had a 65-year marriage (Miles Teller). (Everyone reverts to their happiest age in this afterlife. It makes sense in context.)

Though it features some unseen footage, Baz Luhrmann’s EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert creates a new Elvis concert film mostly by stitching together interview clips with scenes from Presley’s two ‘70s films: Elvis: That’s the Way it Is and Elvis on Tour. Still, the film feels new thanks to smart editing and an emphasis on what made Presley’s Vegas era memorable (without overlooking the schlock). Think of it as a rousing, tuneful epilogue to the story started by Luhrmann’s Elvis.

Junk World is Takahide Hori’s prequel to his 2017 film Junk Head. At least I think it’s a prequel. I missed the original and the story involves a lot (as in centuries) of time travel. Still, I think I followed it most of the time and the imaginative creations and wild ideas kept me engaged even when the film turned confusing.

For action fans who miss the anything-can-happen insanity of Hong Kong’s golden age: The Furious, I’ll just leave that there. You’ll find out why. (One small warning: the Sound of Freedom-esque human trafficking element of the plot is a little rough at times.)

Merely OK or actively annoying: Good News, California Schemin’, Hedda

Recommended without any reservations: Ducking out of theaters for a late-summer/early fall stroll through Toronto parks. I hope to take another one next year (and take in some movies, too).

Discussion