The '80s in 40: 'Scarface' (December 1983)

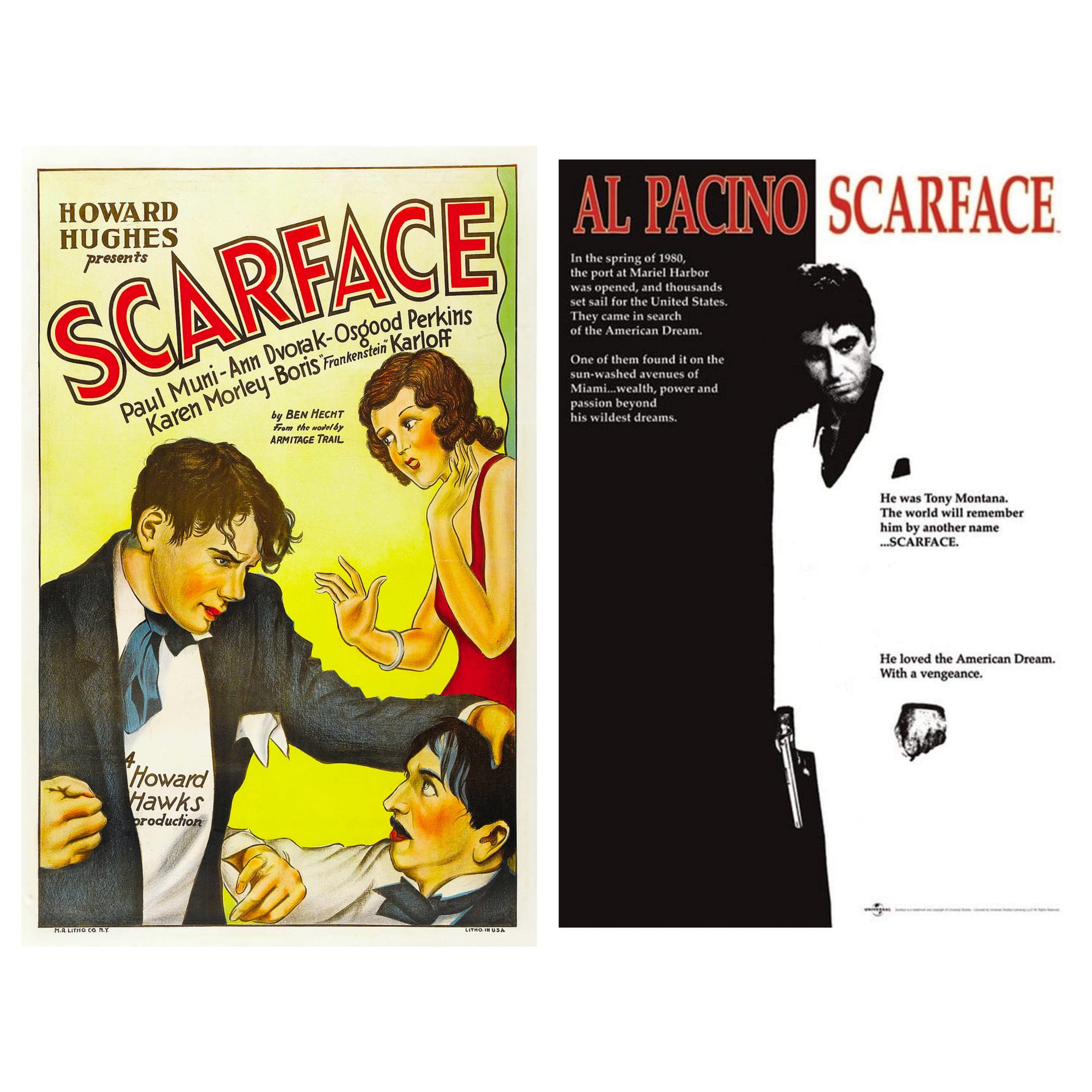

Brian De Palma's 1983 update of Howard Hawks' 1932 gangster movie classic arrived amidst a storm of controversy that's never fully lifted.

The ‘80s in 40 revisits the decade of the 1980s choosing four movies a year, one from each quarter. This entry covers the fourth quarter of 1983.

The first time I watched Brian De Palma’s Scarface, I chuckled when the dedication to Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht appeared on screen over the carnage of the climax’s final moments. Because of Scarface’s notoriety, this, like so many first-time viewings of R-rated films, was at the end of a surreptitious late-night, post-parental bedtime watch after renting the film’s two-tape VHS version from a local video store. At the time, I didn’t know Hecht’s name, only Hawks’. And though I’d seen and loved some of his films, like Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday, I mostly associated Hawks with my vague notions of Hollywood’s classy Golden Age. I could only assume that the garish, provocative, grotesquely violent spectacle I’d just watched—the one that had stirred up such controversy a few years earlier—had virtually nothing to do with the original film. It would be years before I learned how wrong I was.

It’s not just that the 1983 Scarface, directed by De Palma from a script by Oliver Stone, shares the same overarching rise-and-fall plot with the 1932 film, written by Hecht with a handful of other writers, adapted from a novel by Armitage Trail that itself was inspired by the life of Al Capone. It’s not even that De Palma’s Scarface borrows numerous elements and story beats from the original, including a protagonist who’s uncomfortably fixated on his kid sister and who sees a vision of his own future in an advertising slogan reading “The World Is Yours.” Though never as explicitly violent (and 100% chainsaw free), Hawks’ film is just as savage in its way as Scarface’s later incarnation. Both tell the stories of men who see America as a place where fortunes are to be taken and of the country that allows them to thrive, at least for a little while.

Originally given an X rating by the MPAA that was overturned upon appeal, the film’s violence served as both a lightning rod for controversy and an enticement. This also echoes Hawks’ film, a contribution to the already controversial gangster film genre whose commercial success can be partly attributed to the controversy it stirred. An opening text presenting the film as a wake-up call and a mid-film scene of city officials wringing their hands about crime inserted by producer Howard Hughes were attempts to offset moralistic outrage. (Though a pre-Code film, it still ran afoul the not entirely toothless Hays Office.) Even after securing an R rating, the 1983 Scarface inspired concerned articles about the state of violence in American cinema, doubtlessly prompting some moviegoers to check out a film that might not otherwise have been on their radar. “This holiday movie season has to be the most obsessively violent in recent memory,” Knight-Ridder’s Rick Lyman declared in a piece lumping Scarface in with Gorky Park, Christine, and Sudden Impact, all successes, to one degree or another.

This post is for paying members only

Sign up now to read the post and get access to the full library of posts for subscribers only.

✦ Sign up