#52 (tie): ‘Ali: Fear Eats the Soul’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Our trip through Sight & Sound's 100 best films nears the halfway mark with a stop in 1970s Munich, the setting for an unlikely Rainer Werner Fassbinder love story.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)

Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Ranking: #52 (tie)

Previous ranking: #93 (2012)

Premise: Emmi (Brigitte Mira) is a woman in her sixties who’s lived alone in Munich since losing her husband decades before. Coming home from her work as a cleaner one rainy night, she stops in a bar frequented by Arab immigrants. She strikes up a conversation with Ali (El Hedi ben Salem), a considerably younger Moroccan man living as a guest worker. Emmi invites him to stay the night after he walks her home and they initiate a relationship that leads to marriage, confounding Emmi’s children and Ali’s friends, including Barbara (Barbara Valentin), the owner of the bar who has unresolved feelings toward Ali.

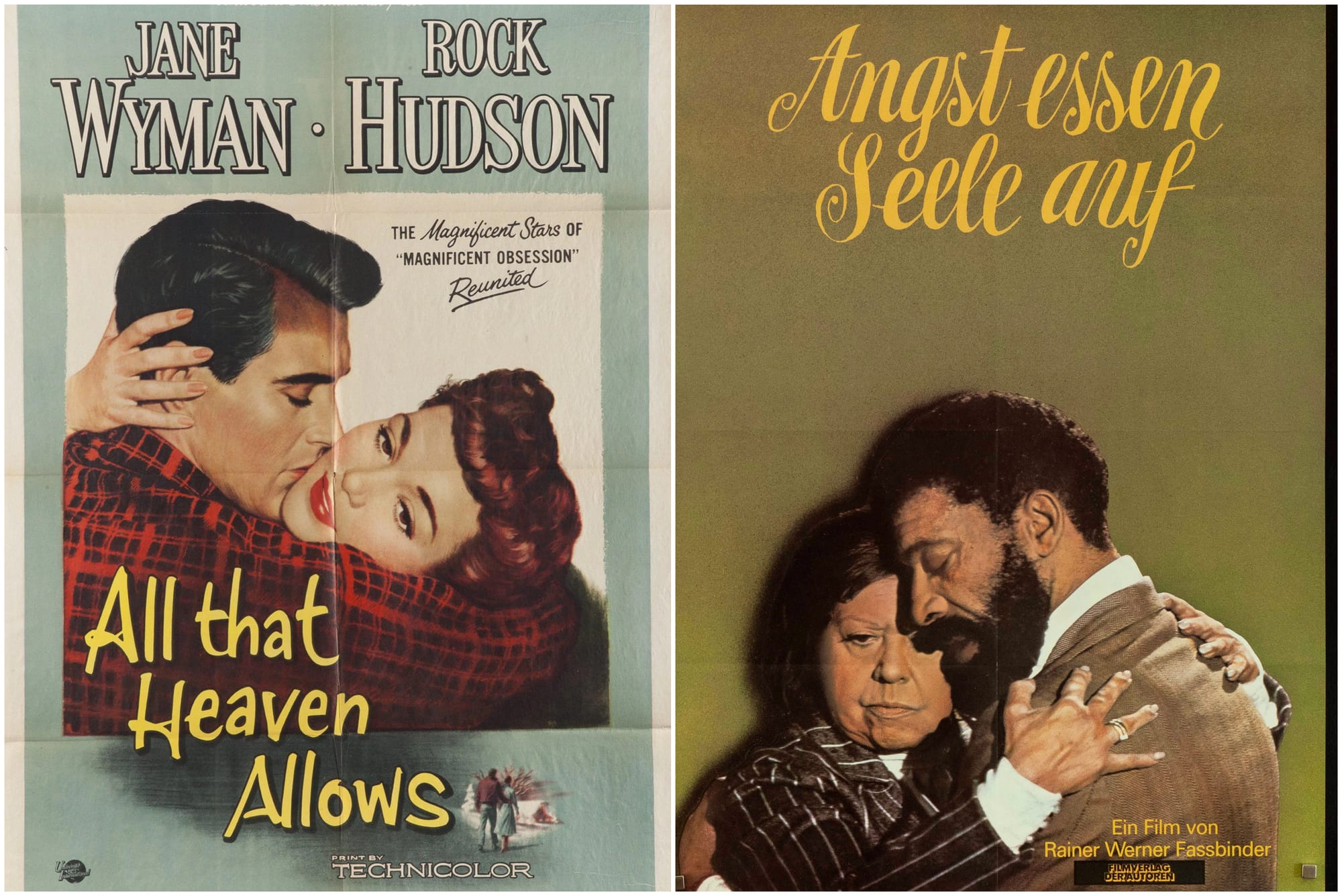

Keith: Scott, I was surprised to learn that Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, which usually appears at or near the top of a list of Fassbinder’s best films, wasn’t conceived as a major work. One of three films Fassbinder released in 1974 (he made 40 before his 1982 death at the age of 37), he shot it in a couple of weeks between the other two: Effi Briest and Martha. I guess I can kind of see it now. Ali takes place in just a few locations and involves a mere handful of characters. It’s also an homage to the films of Douglas Sirk, most obviously All that Heaven Allows, in which Jane Wyman plays a wealthy widow who falls in love with her younger gardener. Ali is its own film, but it’s also the work of a director working from a pre-existing model rather than starting from scratch. He might have thought he was performing an act of homage as a kind of breather between more demanding projects.

It certainly owes more than just its plot to Sirk’s work. The milieu is far more economically downscale and and far less colorful than Sirk’s best known Hollywood melodramas, but Fassbinder shoots in an extremely controlled style, favoring careful, meaningful compositions. We get many shots of characters through doorways that simultaneously make them seem constrained by their surroundings—which are often quite claustrophobic—and gives the images a voyeuristic quality. Much of the film is about others peering into Emmi and Ali’s lives and passing judgement. Fassbinder sometimes makes us complicit in this act.

And, also like Sirk, it’s sometimes hard to know how to take it. Fassbinder stages the scenes at The Asphalt, the bar frequented by Ali and the other Arabs, without a hint of naturalism, in spite of taking place in what appears to be a found location. Emphasis on “appears.” Who knows? Did Fassbinder find it with the poster of the nude satyr and nymph already in place? (I tried to track that image down, only to find that it had similarly baffled others. Apparently it bears the name “Charles Olson” and the year 1969 if you look closely enough.) A later scene where Emmi shows off Ali’s body to some visitors almost seems to be intentionally absurd. And here’s where I admit to not quite knowing how to respond to the film, even though I found myself deeply moved by it. That might also be a function of having Fassbinder as a relative blind spot. I’ve only seen a handful of his films, which I’ve liked without feeling like I fully had a handle on them.

Scott, can you help? Let’s maybe start by how this film made you feel. And were you simultaneously thinking about how this movie fit into its era—the terrorism of the Munich Olympics has apparently made life harder for the guest workers—and what it says about our own and the demonization of immigrants both in the U.S. and elsewhere?

Scott: I love this movie, Keith, though I’ll admit that it’s strange and a little hard to process. On the one hand, it’s highly aestheticized and extremely programmatic, using this twist on All That Heaven Allows as a damning, comprehensive statement on German racism and tribalism. I’m sure we’ll talk about it, but the shift from the hostility Emmi receives from all parties when her relationship goes public to the sudden shift in the way her fellow white Germans treat her later in the film is unnatural to the point of seeming conspiratorial. (More on that later.) On the other hand, the film is genuinely moving, building tremendous intimacy out of Mira and Salem’s performances, which establish chemistry so quickly that we, as an audience, never find their connection as odd as the busybodies and bigots who treat Emmi and Ali so cruelly. For as angry as the Ali: Fear Eats the Soul seems at times about anti-Arab fervor in Germany in the wake of the Munich Olympics—which, we should note, had only happened two years before the film came out—Fassbinder does seem to share a Sirkian conviction that love has a transcendent power.

But in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, not even love is possible outside a larger social context. One of the small but significant differences between this film and All That Heaven Allows is that we’re not talking about the natural attraction between two beautiful humans like the ones played by Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in the Sirk. El Hedi ben Salem was 25 years younger than Brigitte Mira, and somehow the age gap between seems wider due to Salem’s sculpted physique. Add to that his height and their racial differences, and Fassbinder is setting himself up with quite a challenge in that first scene at the bar, which ends with them heading off into the night together. There can’t really be a locking-eyes-across-a-crowded-room moment to account for their chemistry, so Fassbinder and his actors have to sell us on the relationship in another way.

I think it comes down to Emmi and Ali recognizing their similarities, namely a mutual loneliness and alienation, along with occupations that put them on the most humbling end of the working class. They are not accustomed to kindness or companionship. They earn enough money to survive—Emmi in a modest apartment that probably seems too big with her late husband gone, Ali in a single room with five other men—and have routines, which for Ali involves drinking with his buddies at the bar Emmi happens to enter to get out of the rain. It’s a little ironic that Ali approaches her for a dance on a dare, because this old German woman looks so comically out of place, but they’re curious and kind, and one thing leads plausibly to another. The one thing you could chalk up to fate is that if it wasn’t raining, Emmi doesn’t duck into the bar and Ali doesn’t stay at her place after walking her home.

The political context for the film is fascinating. Most obviously, there are the tragic events at the Munich games, which were shocking and sad for the whole world in addition to being an acute embarrassment for the home country. I don’t know enough about German culture in 1974 to say if Fassbinder’s depiction of racism in the city is accurate to the times or heightened for effect, but the film creates an environment that’s thoroughly sinister, where the bar is Ali’s only refuge (and only to a degree, at that) and any appearance he and Emmi make together is greeted with hard stares or more open shows of hostility. There’s no public space they can go where the “wrongness” of their relationship isn’t firmly enforced.

But here’s the smaller part of it that interested me, Keith: What did you make of the Hitler references? There are two points in the film where they come up. In that first conversation that Emmi and Ali have in her apartment, Emmi shares that her father “hated all foreigners” and was into Hitler, and that she was in the Nazi party, too, suggesting that it would have been the ordinary thing for a person like her to do. I think there’s a degree to which we can appreciate Emmi’s growth in getting to this moment where she’s exchanging pleasantries with an Arab at her kitchen table. Then later, after the two get married, Emmi celebrates by taking Ali to an upscale Italian restaurant, noting “this is where Hitler used to eat” and that she’d always wanted to eat there, too. Again, this could be an example of Emmi reclaiming this space that would not have welcomed a person like Ali in the past—and, frankly, doesn’t love to have him there now— but you do wonder about Emmi’s motives.

Which brings me to ask you about the shift that takes place within Emmi and Ali’s marriage in the second half. After many scenes where Emmi is brutally ostracized for the union—by her children, her co-workers, her neighbors, her grocer—you get this beautiful, devastating scene in a public cafe where she breaks down. (“I’m so happy on one hand and on the other, I can’t bear it anymore. Sometimes I wish I were all alone with you in the world.”) She resolves to take a vacation where they can be together without judgment from the “swine” that surrounds them. But when they get back, there’s this jarring shift in which previously hostile people are more welcoming to her, which has the effect of driving a wedge between her and Ali. She’s been welcomed back to her tribe and now she’s othering Ali in various ways and joining the other cleaning ladies in shunning the foreign worker that’s new to the team. How did you take that turn in the film, Keith? What’s on Fassbinder’s mind here?

Keith: I can’t claim to have a definitive answer to that, but I’ll try to offer a theory. But first, let’s talk Hitler’s favorite restaurant. The Osteria Italiana, formerly the Osteria Bavaria, is still in business at the same corner in Munich. The website boasts of its history as “an established haunt for artists, writers, and scientists of the Munich academic quarter” without, quite understandably, referring to Hitler. But the Hitler connection remains strong. You don’t have to look any further than TripAdvisor to see it. That scene feels key to the film. It’s a remnant of an old Germany that’s lingered into the new Germany, which maybe isn’t that new. The staff doesn’t seem thrilled to have Emmi and Ali as customers. ven though this is now expected of them doesn’t mean they like it. (I doubt the restaurant was thrilled with this depiction.)

The casualness with which Emmi refers to Hitler comes off as shocking, but I don’t know that it would be for a woman of her generation or social circle. The Osteria Bavaria might want to erase Hitler from its history and the country as a whole might want to move on. But Hitler was the central figure of German life for decades. To speak of him means summoning up memories of who they were and what they believed when Hitler was in power. The degree to which anyone would feel shame tied to Hitler’s time would have to be tied to how complicit they feel in what happened and/or how much their own opinion has shifted. Maybe their beliefs still align with Hitler, even if they don’t say it out loud since those beliefs became impermissible. (And maybe they feel these conditions won’t last. We’ve certainly seen our share of once-verboten beliefs being allowed to resurface in the public sphere of late.)

We don’t learn that much about Emmi’s past, but she doesn’t strike me as someone who spent her youth feeling passionately about politics, one way or another. However committed she might be to her relationship with Ali in the face of opposition from, well, everyone, it might be her first act of rebellion. As for what Fassbinder’s doing in the post-vacation sequence, I don’t think it’s pretty. Those around Emmi budge just enough to allow room back in the fold for her. But it’s almost like it’s conditional. Emmi has to behave in dehumanizing ways toward Ali for it to happen. Ali, in turn, sleeps with Barbara, which seems like a desperate search for intimacy but also plays into the Arab stereotypes expressed by other characters. (Also, as Chris Fujiawara has noted, Emmi’s co-workers have moved on to treating a new arrival from Yugoslavia with the derision they once directed at Emmi.) It’s almost as if the movie reaches a pat conclusion about standing up to prejudice, then keeps going past the point where such stories usually end and has to consider what happens next.

Yet I think the end of this movie is lovely, as powerful in its own way as the amazing final scene of All That Heaven Allows, in part because it has depicted all this ugliness. The doctor may not hold out much hope for Ali’s future but whatever it might be, Emmi says she’ll be there. And I believe her, too. Maybe it’s my own stupid optimism and fondness for these characters, but to my eyes the second half of this movie is the story of a couple experiencing and getting past a crisis. Emmi has seen the error of her ways making Ali less inclined to stay. If Germany really is to reinvent itself, it’s going to be from the ground up as much, if not more, as from the top down.

Scott, I’d love to hear your take on these later scenes when the marriage seems to sour. And am I unreasonably optimistic about the end of this movie? Also, would you eat at Hitler’s favorite restaurant or would it be too weird? The other TripAdvisor reviews are pretty mixed.

Scott: Let’s start with the ending, Keith, because I think it’s lovely too. Fassbinder loved Sirk, so it follows that he would share with Sirk an optimism about the human capacity for love and redemption, at least in this particular context. Emmi and Ali get put through the wringer in this film, but there could be an ending where Fassbinder concludes that the societal forces at play are simply too powerful for either of them to overcome. The film is so damning of then-contemporary prejudices, after all, and you could imagine a tearful parting of the ways or something much more pessimistic, like Emmi falling in line with the “stupid swine” that once tormented her. We can see how appealing it is for her to break off again with her co-workers and thoughtlessly abandon the foreign worker that they all hold in contempt. She doesn’t seem to give it a second thought, even though she was once the person they left behind on the stairs.

The medical particulars of Ali’s situation tug on the heartstrings, too. I love the last scene at the bar toward the end where Emmi strides into what must now feel like enemy territory—though it’s not like she was greeted warmly from the start—and requests that “their song,” called “The Black Gypsy,” be played on the jukebox. That the music is his music, rather than the half of the jukebox reserved for Germans like Emmi, is a significant concession on her part and her willingness to forgive his affair with Barbara follows along those lines, too. “I know how old I am,” she says before setting a different set of terms. “But when we’re together, I want us only to be nice to each other.” Not long after she says those words, Ali collapses from what a doctor later tells Emmi is a stomach ulcer due to stress.

I think Ali’s ulcer is important to the film’s understanding of the social pressures both of them face, which Fassbinder suggests are not on the same level. A doctor tells her that such ulcers are common to foreign workers and that he expects Ali to be back again in six months, in part because he doesn’t have the luxury to convalesce, but also because an Arab in Germany can expect no reprieve from judgment. By marrying Ali, Emmi certainly gets a taste of the hostility and prejudice he experiences every day, but she can escape it whenever he’s not around. To end this movie by having her hold his hand and commit herself to easing the stress on him as much as possible is so moving. Emmi has truly evolved as a person, which you don’t expect from someone her age, on-screen or off. Her views have not calcified.

(As a small aside here, I was happy to see Emmi acknowledge that she’s not an ideal partner for a young, handsome man like Ali, because if Fassbinder fully embraced the fanciful idea that they make sense as a couple, it would be dehumanizing for Ali. Is he supposed to be content to have this old German woman as his sole sexual partner for as long as they both shall live? Emmi is ultimately seeking intimacy and companionship here, and Ali can meet her on those terms without the film having to deny needs that she cannot satisfy.)

As for the scenes where the marriage seems to sour, I’m again struck by their abruptness, because the shift happens right after they come back from vacation and are ostensibly settling into their lives together. It honestly feels like all of Emmi’s white friends, neighbors, and family members held a secret strategy meeting while they were gone and decided on a new tactic for ripping her and Ali apart. But you can maybe also see that they’re acting out of self-interest: If Ali is going to live in Emmi’s apartment permanently, maybe her neighbors can exploit her eagerness to make amends by having her order him to do manual labor for them? Or if the nearby supermarket is peeling customers away, is it really good business for a small grocer to ban a regular like Emmi from shopping at his store? I don’t know if they’re deliberately trying to introduce a new kind of tension in the marriage, but that’s exactly what happens. It’s comforting for Emmi to be welcomed back into the tribe, even if that means regressing into the attitudes toward foreigners that she had seemingly rejected.

As for Hitler’s favorite Italian restaurant, I’m not sure that sitting at “table eight” at the Osteria Baveria would be on my itinerary, in part because Google reviews are alerting me to several more appealing options in Munich and in part because this ghoulish sort of tourism reminds me of the time erstwhile far-right Republican congressman Madison Cawthorn raved about visiting Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest,” which had been on his bucket list. But to bring Ali: Fear Eats the Soul to the present time, where overt Nazism is creeping into the political mainstream, I think the film understands how such gutter racism never goes away, even during times when society is successful in suppressing and marginalizing it. After the tragedy at the Munich games, that low hum of anti-Arab hatred surely buzzed much louder. Movies like Fassbinder’s do their small part in exposing these sins and appealing to our better angels.

We’re heading into the Top 50 now, Revealers! The next, uh, two-and-a-half-plus years on here will hit us with the biggest canonical classics and a few more recent favorites like…

Next: The Piano (1992)

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59: Sans Soleil

#54 (tie): The Apartment

#54 (tie): Battleship Potemkin

#54 (tie): Blade Runner

#54 (tie): Sherlock Jr.

#52 (tie): Contempt

#52 (tie): News From Home

Discussion