#54 (tie): ‘Battleship Potemkin’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 masterpiece dramatizes one of the inciting incidents of the Russian Revolution while rewriting how movies could be used to tell stories, one shot at a time.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Dir. Sergei Eisenstein

Ranking: #54 (tie)

Previous ranking: #11 (2012), #11 (2002), #6 (1992), #6 (1982), #3 (1972), #6 (1962), #4 (1952)

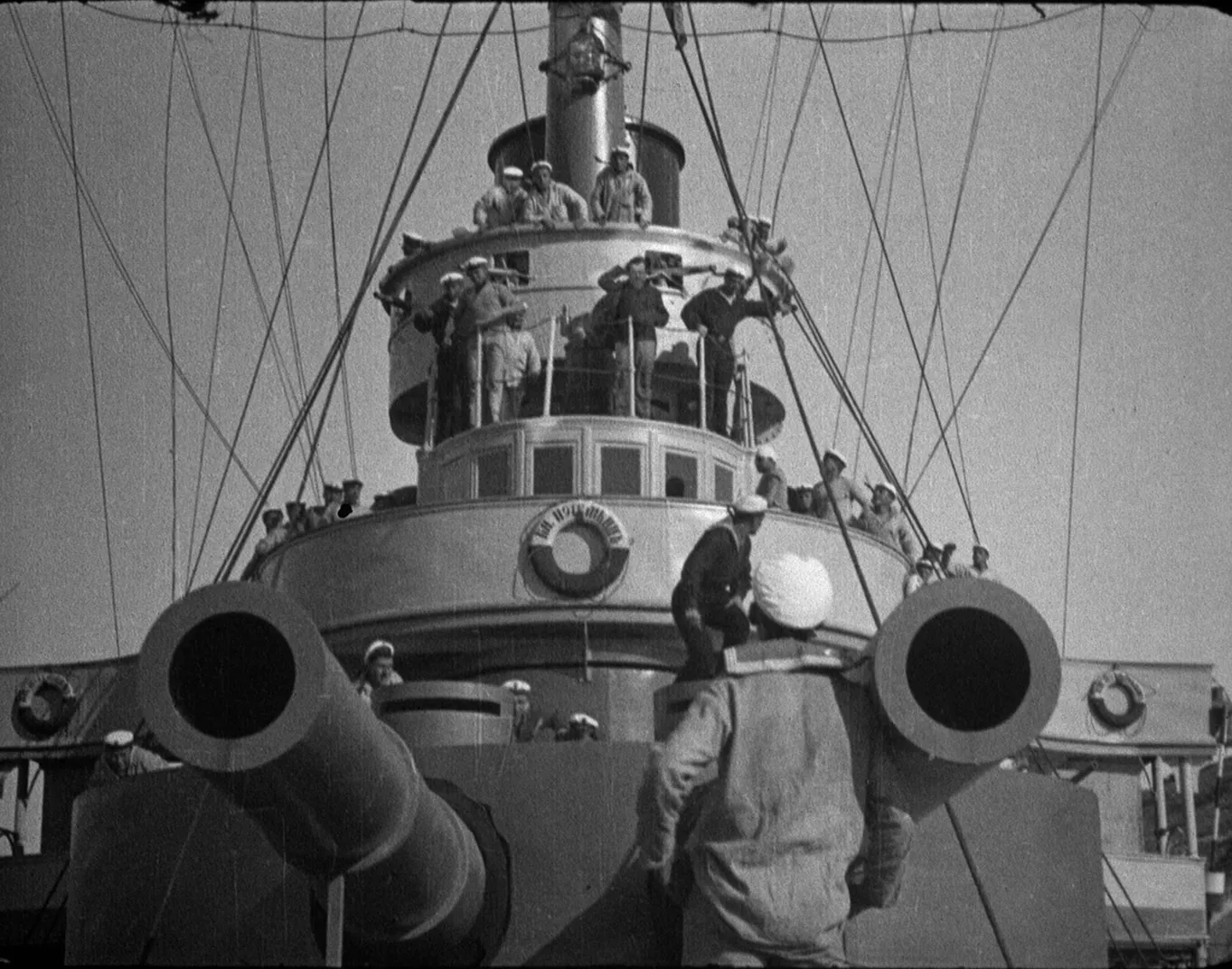

Premise: June 1905: The Russian forces are stretched thin by the disastrous Russo-Japanese War. Unrest against the rule of Tsar Nicholas II is at an all-time high and extends to members of the military. In the Black Sea, the battleship Potemkin endures dehumanizing conditions. Their discontent reaches a breaking point when they’re served borscht filled with rotten, maggot-infested meat and those who refuse to eat it are targeted for execution. The tumult that follows heightens when they reach the shores of Odessa.

Keith: Scott, it’s here that I need to announce that I am leaving this profession to join the Russian Revolution. This film persuaded me that the Tsar has finally gone too far and we can sit idly by no longer. Also, no matter what they say, washing rotten meat with brine does not make it edible. It does not even get rid of all the maggots!

I guess before I leave I should at least talk about the film that led me to this conclusion: Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, a dramatic breakthrough in editing filled with stunning visuals, gripping action scenes, and soaring emotions that’s also a highly effective piece of propaganda. Battleship Potemkin is one of those films you can point to and say that the entire course of film history would look different if it did not exist. Even if you haven’t seen this movie before, you’ve felt it, both via obvious homages (most frequently to the Odessa Steps sequence) and in the language of filmmaking itself. I’m not expert enough to unpack Eisenstein’s theories of editing, which evolved over the course of his career, but I do know I still see echoes of the powerful ways he juxtaposes images in films being made 100 years later.

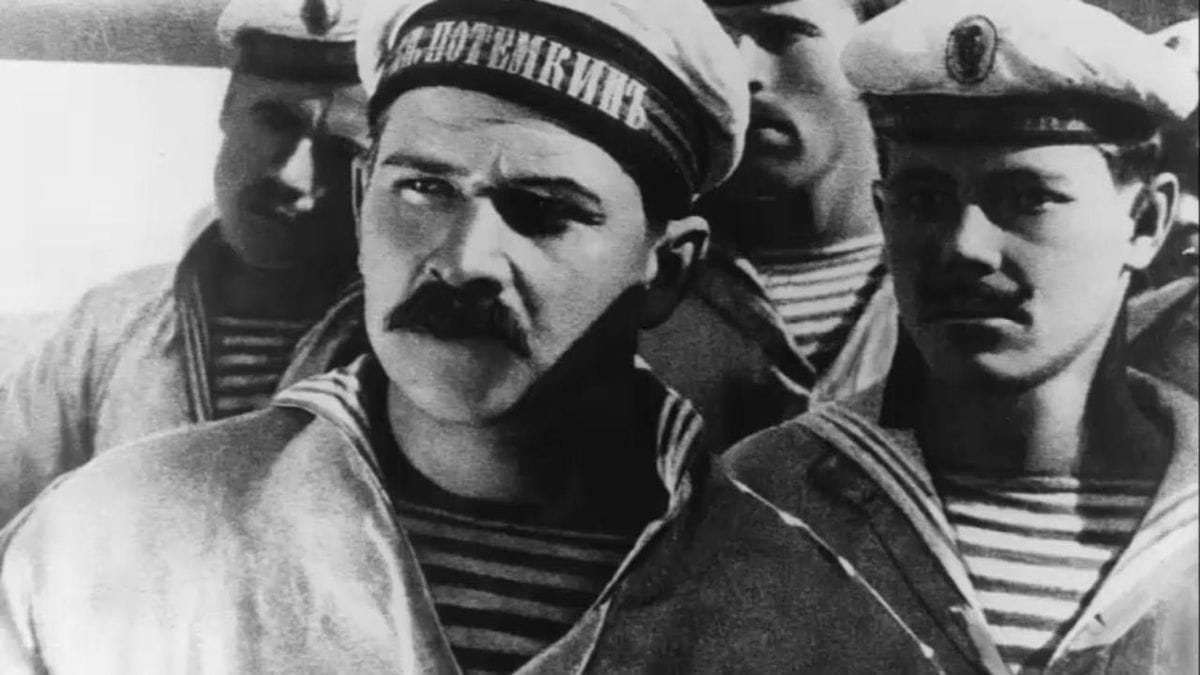

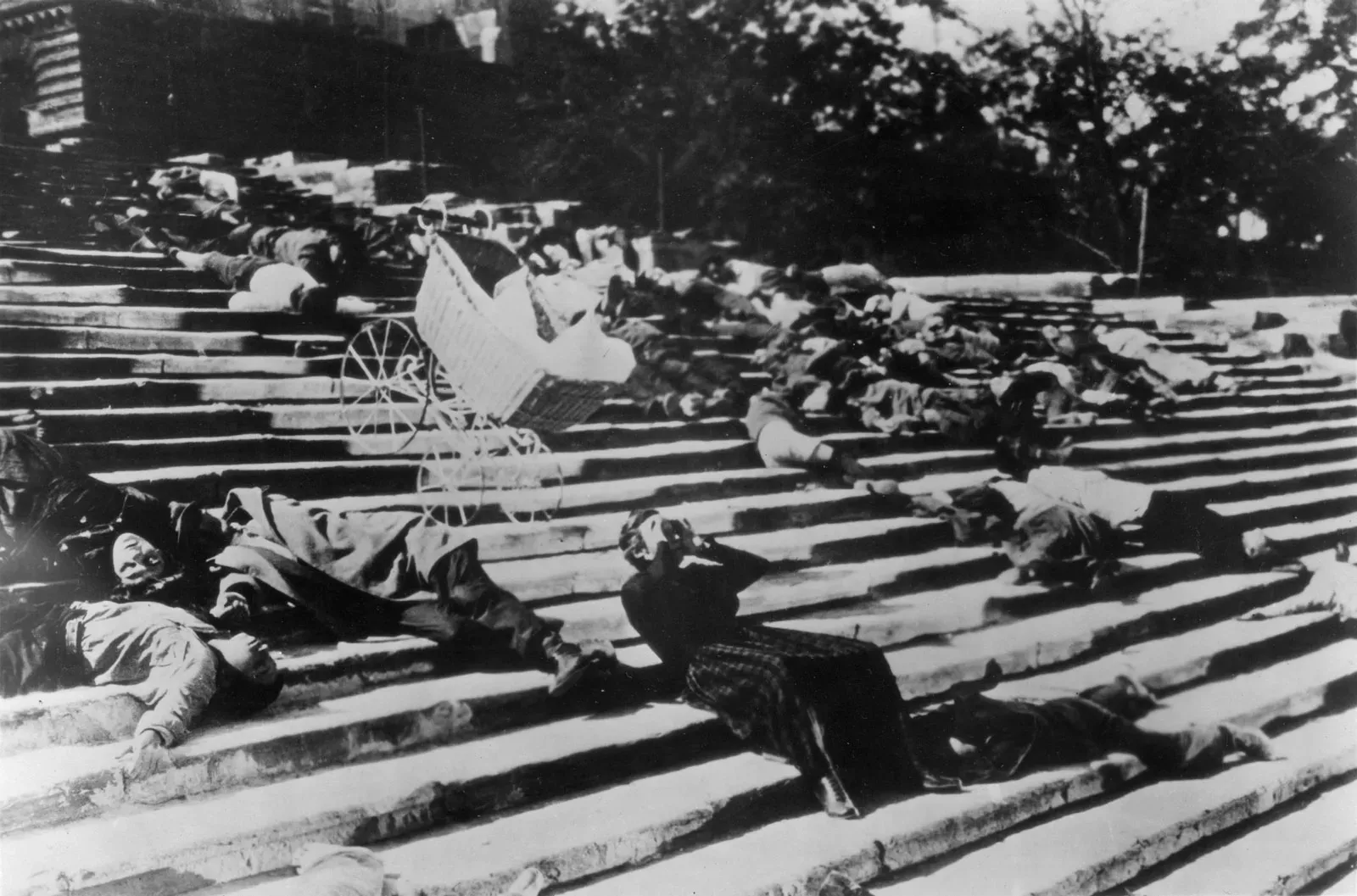

I’m sure we’ll want to get into some of those individual moments over the course of this conversation, Scott, but maybe we should start with the big picture. Even if you went into Battleship Potemkin with no knowledge of Eisenstein’s place in film history or the film’s political context—it was made to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Russian revolution of 1905—it would still work as a powerful viewing experience. That’s partly because it presents an unambiguous struggle between good and evil. The crew of the Potemkin, or at least the enlisted men, live in degrading conditions under the oppressive command of callous officers. Eisenstein even gives viewers a literal mustache-twirling villain in Ippolit Giliarovsky (Grigori Aleksandrov). The Odessa Steps sequence depicts moments of child endangerment, and death, even beyond the famous out-of-control baby carriage.

Yet even though I can feel Eisenstein working a propagandistic agenda with the movie, it still works as a piece of drama. I think that’s partly because Eisenstein puts so much emphasis on the humanity of his heroes. You can feel the heat and discomfort in those early shots of sailors sleeping uneasily in cots. And as masterful as the Odessa scenes are in depicting an attack on the masses, it’s the images of individuals that make it unforgettable, from the amputee fleeing the soldiers to the mother holding her dead child. Maybe it’s a cliché to say the film gives history a human face, but it’s an apt cliché.

Scott, I had not seen this movie in quite a while and I’m pretty sure I saw one of the many censored versions when I watched it on VHS. How did it work for you this time? One thing that struck me: this was made to promote a specific political agenda but the techniques Eisenstein employed could serve other ideologies. Or could they? Joseph Goebbels angered Eisenstein by asking his propagandists to use Potemkin as a model, prompting the director to write an open letter that ran in the New York Times in 1934 that took Goebbels to task for attempting to pervert “the whole triumphant development of our film art during the last few years.” The letter then added: We all know that only real life, the truth about life and the realistic presentation of life can serve as the basis for genuine art.” Was Eisenstein right? For all its propagandistic power, Battleship Potemkin largely stays true to the facts of history, which are, well, not that flattering to the forces of the Tsar. But could they just as effectively be used to tell lies?

Scott: Holy smokes, that open letter is a scorcher! “How do you dare to ask your film artists to give truthful pictures of life without enjoining them, first of all, to trumpet forth to the world the torments of the thousands who are being tortured to death in the catacombs of your prisons and in the casements of your jails? Where do you find the brazenness to talk about the truth at all after you have erected such a Babylonian tower of infamies and lies in Leipzig?” How refreshing to see an artist like Eisenstein meeting that historical moment with such passion. (If American filmmakers would care to do so, say, now-ish, that would be appreciated, though most of our propagandists are thriving artlessly on cable news.)

The notion of “truth” in any piece of cinema, particularly one with a propagandistic bent like Battleship Potemkin, must be scrutinized heavily in my view, even if Eisenstein does commit himself to the broad strokes of history, as you assert. I would imagine Goebbels was more interested in harnessing the power of Eisenstein’s cinematic effects, just as he did with Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, which we discussed late last year for this project. But you can see how Eisenstein’s alignment with the oppressed wouldn’t have squared with the Nazi movement, and there’s even a key moment in Potemkin where a man trying to incite the frenzied crowd to “Kill the Jews” is tackled by them instead.

Before getting too deep into Potemkin, however, I have to point out how conspicuously the film has fallen in the 2022 poll. It has been a staple of the poll since its inception in 1952, when it debuted at #4, and it stayed in the Top 10 every year until the 21st century, when it slipped to #11 in both the 2002 and 2012 polls and now all the way down to #54. If I’m being a curmudgeon about the poll, I’d say that the eagerness to disrupt the canon has gotten out of hand here, but then again, I did not help matters by not including Battleship Potemkin on my ballot. (Only submitting a Top 10 is rough, I have to say, and even my relatively conservative selections made room for two films from 1981.)

To me, it’s notable to see the three Russian films that leapfrogged it: Two by Andrei Tarkovski, Stalker (#43) and Mirror (#31)—which gives him a whopping three in the Top 100, including the previously covered Andrei Rublev (#67)—and Dziga Vertov’s Man With the Movie Camera, which cracked the Top 10 at #9. The Vertov placed high in the 2012 poll, too, at #8, but that was a significant leap from the 2002 edition, where it was #31. I’m not sure what to make of this, exactly, other than voters finding Vertov’s advances in experimental cinema more significant in the 21st century than Eisenstein’s contributions to more traditional narrative cinema.

There’s also quite a bit of competition with Battleship Potemkin among Eisenstein’s Russian contemporaries, chiefly films like Vsevolod Pudovkin’s 1926 Mother and, my favorite, Alexander Dovzhenko’s 1930 film Earth, which includes some of the most startlingly beautiful pastoral images you’ll ever see. Perhaps it’s inevitable that as we go deeper into this second century of movies and the winnowing process for a list like Sight and Sound gets even harder, silent films like Potemkin, the great building blocks of cinema, will continue their downward slide. Yet I’m always extra-riveted by watching films like Potemkin that advanced the language of cinema so profoundly, and I think in this specific case, its revolutionary aesthetics complement its understanding of revolutionary history. Eisenstein was up to a mammoth task.

Watching Potemkin this time, I had of course remembered the uprising over the tainted meat in the film’s first act and the oft-imitated Odessa Steps sequence (at least the baby carriage part), but what really knocked me out this time were the quiet-before-the-storm moments between the big uprising sequences. I’m thinking specifically of the beginning of Part Three, when the ship is coming into port at Odessa with Vakulenchuk’s martyred body in tow. It’s dusk and a little foggy, and Eisenstein allows his painterly images to linger for a while without pushing the action forward. I want to get into how he constructs a big setpiece like the Odessa Steps in my next missive, but I think he’s laying the groundwork here already. The audience has just been aroused by this dramatic mutiny at sea and there’s rebellion to come on dry land, but now we can feel that uncertainty a bit. I’m reminded a little of those early moments in Saving Private Ryan where the landing crafts are approaching Omaha Beach but aren’t taking fire yet. You live with that dread for a while before the inevitable bloodletting.

That’s great filmmaking, and so much of a piece with the events that follow. Any standout stretches for you, Keith? And how do you imagine such a film would play to audiences in 1925?

Keith: I similarly found myself struck by the way Eisenstein lingers on his characters’ faces. We don’t really get to know any of these characters and most, apart from Vakulenchuk (Aleksandr Antonov), Giliarovsky and a handful of others, barely emerge as characters at all. But Eisenstein frames them with incredible care and lets their expressions convey their anger and virtue. I was also struck by an early shot of the men in their hammocks that capture both their discomfort and unity. It’s a horrible situation but they’re all in it together. In some ways they’re more types than individuals, but, well, this is communist propaganda. That makes sense.

As to how it would play in 1925, I don’t know enough about where Russian politics were at that moment to speculate. But if I were a leader of a fledgling nation hoping to shore up support eight years into its existence, I doubt I could imagine a better reminder of what the revolution was supposed to be all about than this film. Which might suggest another reason why the film has dropped on the list a bit. Appreciating it now requires forgetting for its (brisk) running time how all that turned out. That might also be why there’s a ceiling for my appreciation of the film, albeit an extremely high one. As effective as Potemkin is, you can still feel the mechanics at times. It’s hard to ignore that you’re being pushed toward a particular point of view, no matter how closely it sticks to the facts. Any system that forces men to eat rotten meat then kills them if they refuse should get a well-deserved toppling.

Another thought that occurred to me: When people talk about the introduction of sound setting back the art of filmmaking as developed in the silent era (at least for a bit), this is what they’re talking about. Potemkin’s influence, of course, stretches into the sound era and the post-silent Eisenstein films I’ve seen confirm he adapted well. But this is the work of a director unburdened of any demands except creating images and stitching them together. It would take just two years for The Jazz Singer to make this way of working outmoded.

Okay, Scott: The Odessa Steps sequence. Let me set you up? Why does it work so well? Where do you see its influence? And why is that baby carriage so famous? (I have my own thoughts, but I want to hear yours first.)

Scott: Before getting to the Odessa Steps sequence, I want to address the issue of Potemkin as propaganda and the possible limitations that might present to us (and other critics and possible Sight and Sound poll voters) in appreciating the film. Because that issue has arisen, too, in the discussion over another Russian propaganda film, Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba, a virtually peerless cinematic tour-de-force that has also been described, accurately, as communist kitsch. What’s immediately evident in both films, as with all propaganda, is the flattening of the individual in order to arrive at a larger, unifying political statement. That’s not to say that Eisenstein and Katatozov cannot harness the power of the individual in their own way: To use your words on Potemkin, they “give history a human face,” albeit without the attendant complexities of, say, doubt or motives beyond their broad place in the human struggle. As much as I love Potemkin and I Am Cuba—and as much as I recognize that nuances of character don’t have to be the goal of every movie—their inherent reductiveness is, well, anti-human.

At the same time, and this brings us back to the Odessa Steps sequence, you can feel history as an overwhelming force in determining the fate of the individual. One of the exhilarating/terrifying aspects of being on the Earth is that we’re subject to historical changes beyond our ability to control, and a film like Potemkin can have you believe that sweeping change is possible, even if that means some individual lives will be sacrificed in the process. The sequence is extremely important and endlessly influential as a feat of editing, of course, but the raw materials that Eisenstein starts with are extraordinary, starting with the faces and then, from a wider view, the sheer size of the ordinary people populating this space and the detachment of Cossacks gunning them down. It’s hard not to be affected by that dynamic, of the mass-scale injustice of a government shooting at its own people and the eventual triumph of an united rebellion toppling that same force.

What Eisenstein understood better than anyone at the time was how to amass the building blocks of a suspense sequence. As I suggested in my earlier missive with those hushed scenes of the Odessa harbor before the violence starts, Eisenstein is already working on our emotions, allowing some anticipation and dread to mount before we ever reach dry land. He then connects the city with the battleship through these “white-winged skiffs” that bring much-needed food and supplies to the depleted ship. It seems ridiculous to talk about now, when we should know better, but it’s important for a setpiece like the Odessa Steps to spend time simply establishing spatial relationships and ramping up slowly before the action starts to accelerate. Too many movies today try to skip to the action and hope that kinetic energy and speed alone will compensate for the fact that they haven’t situated the audience in the setting or set up relationships between pieces of the action.

With the Odessa Steps, Eisenstein gives you these mass movements of unarmed humans and their dismounted attackers while drawing our focus on a handful of vivid faces: The limbless man forced to hoist himself down the stairs; a mother who rushes to her boy after he’s gunned in the head and the mob tramples down around him; and, of course, the mother frantically guarding her baby as its carriage rolls precariously close to the edge of the staircase. The symbolism of this last element is so powerful, from this bond between mother and child being broken by state violence to the child’s future literally hanging in the balance. It was funny and little audacious to see Brian De Palma borrow the baby carriage for The Untouchables, but as someone who appreciates the big De Palma setpiece, with all of its patience and attention to detail, I like how he affirms the timeless value of Eisenstein’s filmmaking. And compared to other silent films of the era I’ve seen, Potemkin feels like a great and eternally important leap forward in filmmaking craft.

So was your read on the baby carriage and that sequence, Keith? And what’s next on the docket?

Keith: I think you got it, really. It’s a part of Eisenstein’s manipulation of scale. Earlier, an extremely big story—the history of the Russian Revolution (first phase)—is a bigger version of the story of a single mutiny, which is in turn the bigger version of the story of sailors refusing an inedible meal. It’s hard to contemplate the death of a thousand people (which were in turn a prelude to the October Pogrom later that year, hence Eisenstein’s inclusion of the anti-semitic instigator), but the loss of a baby? That’s easier to wrap your head around. If you’ll allow a bit of cultural stereotyping, it’s a Matryoshka-like approach to storytelling.

As for what’s next, let’s jump from the past to the future as we travel to the far-off year of… 2019? That can only mean it’s time for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, the third of five films tied at #54.

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59 Sans Soleil

#54 (tie) The Apartment

Discussion