#54 (tie): 'Blade Runner': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

A flop in 1982, Ridley Scott's loose adaptation of a Philip K. Dick novel explores the nebulous definition of what it means to be human via a noir-inspired story of killer robots and those that killed them.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Blade Runner (1982)

Dir. Ridley Scott

Ranking: #54 (tie)

Previous ranking: #69 (2012), #45 (2002)

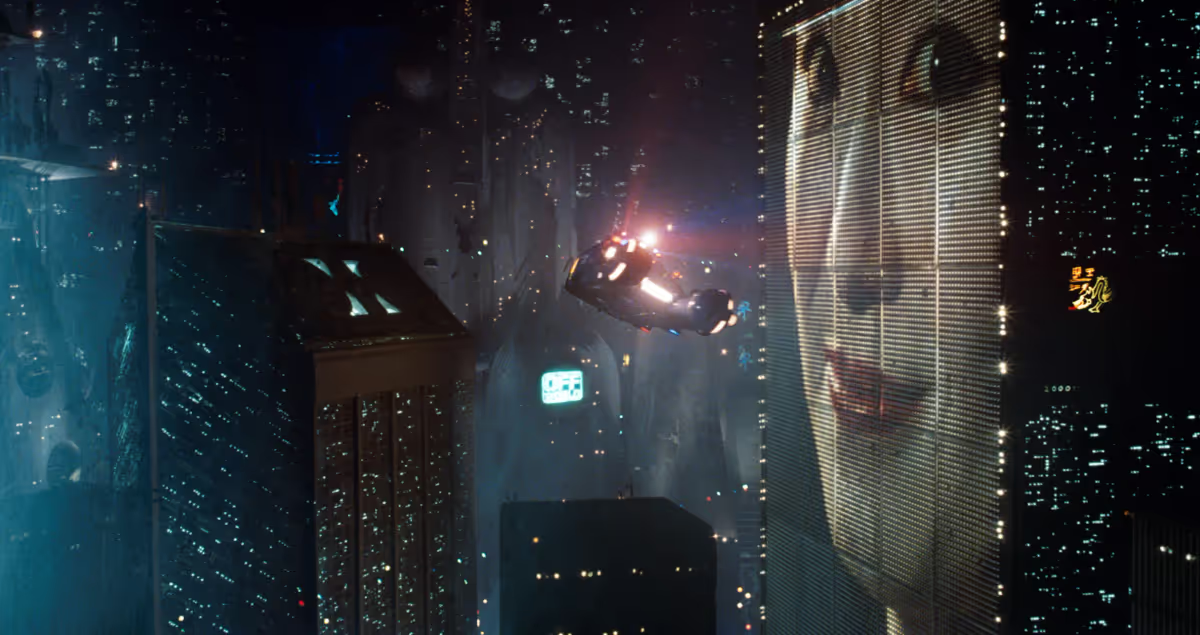

Premise: 2019: Much of the Earth’s population has departed for a better life on the off-world colonies. Los Angeles is now an underpopulated metropolis, a cluttered, rain-soaked, polyglot urban center filled with desperate characters. These include a handful of replicants, androids that are virtually indistinguishable from humans. Some have rebelled and escaped their off-world life and live as fugitives, possibly with the intent of taking down Tyrell Corporation, the company that created them. Those in charge of hunting down the replicants are called blade runners. These include Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), who reluctantly agrees to “retire” the fugitives.

Keith: Scott, may I ask you a personal question? Have you ever retired a human by mistake? I’m guessing not. Film criticism is historically not a profession with a high body count. So it might not be relevant to our lives, but it’s certainly the question at the heart of Blade Runner. There’s a lot going on in this film, but they all stem from this: What happens when you create a machine that perfectly mimics humanity? Does that make the machine human? Does it make humanity seem a bit more like machinery? What rights, if any, do such creations have? If a simulation is perfect, perhaps even “more human than human,” can you even call it a simulation at all?

Here are the correct answers… I’m kidding of course. Directed by Ridley Scott from a script by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples adapting Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Blade Runner is not the sort of film that’s interested in providing answers or being “solved.” In fact, I think recognition as a modern classic can be directly traced to the 1992 release of Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut, a project that allowed Scott to remove some studio-imposed elements, most notably the voiceover narration, that made some of the film’s narrative less opaque. (It’s certainly what made me an admirer of the film. One of these days I should probably watch the original theatrical cut, I guess.) That its ascent coincided with the rise of the internet, where a science fiction film filled with provocative ideas and stunning visuals is sure to provoke discussion, probably can’t be dismissed either. For evidence, allow me to direct you to the 1993 document “Blade Runner FAQ” as compiled by Murray Chapman, surely one of the most-read items from this era of online film appreciation.

That’s not to suggest that Blade Runner is an incomprehensible film, of course. I just think that its ambiguity is one of its greatest strengths, to say nothing, for the moment, of the stunning design of the world. Whatever the flaws of the original theatrical cut, I’m still a bit baffled how critics of the era could file middling reviews of a film that looks and sounds like this in 1982. Many grudgingly admitted the film looked great but that was all there was to it. (Gene Siskel: “Dazzling for the first 20 minutes and then what?”) I think the look of the film—the combined efforts of, among many others, Scott, cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, futurist Syd Mead, and effects hero Douglas Trumbull—work hand-in-hand with the story. Everything I see makes me want to know more about the world of the film. “Do you like our owl?” What kind of question is that and why does Rachael (Sean Young) ask it?

I want to kick this back to you with one of the film’s biggest questions. And, don’t worry, I don’t expect you to answer it. I think I’d seen the film a couple of times—and possibly read that FAQ—before it occurred to me that Deckard might be a replicant himself. (It was also the first thing that occurred to my 14-year-old daughter, who watched the film with me this time, another sign that she’s smarter than her dad.) I’d love to hear your thoughts on this matter, Scott, but I’d also like your thoughts about the question itself. What does it mean to the film if he is? And what does it mean if he isn’t?

Scott: First off, I’m really excited to contribute to the internet discussion of Blade Runner, which is about as tears-in-rain as the discourse gets in terms of relevancy. (But Google “ousmane sembene black girl discussion” and bam, we’re the second hit!) Second, I think I retired Alejandro González Iñárritu after that Bird Man review— [touches earpiece] “Wait, it won how many Oscars?!” —and I have created a permission structure for thinking poorly of Shrek, so critics of the future won’t have randos hunting them down on Instagram to mock their homemade loaf of rosemary-olive oil focaccia bread. Honestly, it’s a little disappointing (if understandable) that I got more attention for those pans than I ever did for a review of a film I championed, but that’s a discussion for another day.

As for Blade Runner, I’ll confess to having struggled with this film over the years, at least until the Director’s Cut came along and the experience of watching it changed profoundly. I did not see the film when it came out—at 11-years-old, I’m certain I’d have been utterly baffled by it—but my first viewing was at a pre-Director’s Cut time when its reputation was still a bit underwater with critics. Losing the narration not only restores some mystery to Blade Runner, but gives it a consistent and coherent tone that’s more in the realm of film poetry, with Cronenweth’s images and Vangelis’ score lifting along without needing any help from a somnambulant Harrison Ford. As much as I’ve come around on the film—and as influential as it continues to be—I remain a little taken aback by it appearing so high on the Sight and Sound Top 100, debuting at #45 despite its middling reviews and poor box office in 1982. Has there ever been an alternate cut of a movie that’s raised its profile like Blade Runner? I can’t think of anything quite like it, save maybe for Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, which is its own special case. (We’ll get to that one in two or three years.)

To answer your question on the “Is Deckard a replicant?” debate, I’m in the “accept the mystery” camp on the issue and I suspect the film is, too. Certainly Ford’s acting style here—a robotic noir, hard-bitten yet stoic—makes him seem extremely replicant-like, though you could argue that the passion he displays for Rachael makes him seem human. But then again, we also witness flashes of childlike vulnerability and grace from the likes of Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and Pris (Daryl Hannah), so who’s to say? I think one of the fundamental points of Blade Runner is that a future has been created where the distinction is meaningless in most respects. For one, we’re told the Voight-Kampff test usually takes 20 or 30 questions to distinguish a human from a replicant, and it takes about 100 for Deckard to finally arrive at an answer on Rachael—one that she’s legitimately heartbroken to hear. This isn’t a situation where you run an X-ray or pull back to skin to discover an android’s synthetic insides. I guess you can’t make a quick guess until one of them is beating the hell out of you (or checkmating their creator in two moves).

The questions you ask at the beginning of your missive, Keith, imply most of what needs to be said about the limited relevance of the Deckard replicant question: “What happens when you create a machine that perfectly mimics humanity? Does that make the machine human? Does it make humanity seem a bit more like machinery?” That’s just it: Los Angeles 2019 feels like an end-of-days situation for humanity, despite the astounding technological advances (and climate changes) that turned out to be a bit ahead of the real Los Angeles in 2019. Mankind has reached a tech-fueled evolutionary tipping point where humans are barely distinguishable from machines. But it cuts both ways: The opening titles inform us that the NEXUS 6 replicants are superior to humans in strength and agility, though we discover they have a much more limited mortality. But that conspicuous spark of life that might separate man from machine is also extinguished. It’s as if humanity is as resigned to obsolescence as the replicates they’ve created.

Obviously, Philip K. Dick deserves credit for a lot of these themes, but we should probably talk about how Ridley Scott and company bring them to life, given the immense influence Blade Runner would have over science-fiction films to follow. Those opening shots, Keith! I share your befuddlement over the ho-hum reaction to the film from critics just for the failure to acknowledge a truly important leap forward in world-building here. What are some of the standout details for you cinematically? And what kind of impact do they have on your impression of the film on the whole?

Keith: The opening scene of Blade Runner is one of those moments that grabs you by the proverbial lapels and demands you pay attention. Even apart from the visuals, the combination of the Vangelis music, the muted sound effects of flames spewing into the sky, and the first film’s first spinner flying across the sky has an enveloping quality that commands complete focus. We know where and when we are—Los Angeles, 2019—but what has happened to it? The landscape looks both familiar and otherworldly, if not quite futuristic. I think the conspicuous influences of the production design, which range from the Egyptian pyramids to the Los Angeles of noir movies, keeps Blade Runner from feeling like a prediction that never came true, even though it doesn’t square with the 2019 we experienced.

When Paris Review asked William Gibson about his complicated relationship with Blade Runner, a film released as Gibson was writing that other pillar of what came to be known as cyberpunk, Neuromancer, Gibson said:

[T]he simplest and most radical thing that Ridley Scott did in Blade Runner was to put urban archaeology in every frame. It hadn’t been obvious to mainstream American science fiction that cities are like compost heaps—just layers and layers of stuff. In cities, the past and the present and the future can all be totally adjacent. In Europe, that’s just life—it’s not science fiction, it’s not fantasy. But in American science fiction, the city in the future was always brand-new, every square inch of it.

The world of the film layers futuristic elements on top of the Los Angeles we know. That some of these elements, like Rachael’s fashion sense and other noir era trappings, also hearken back to the past creates a disorienting feeling thatthe past and the future have started collapsing into one another. (Shades of another Dick novel, Ubik.) That, as Gibson points out elsewhere in the interview, Blade Runner itself became an influence on design and fashion only further complicates that effect. The film’s 2019 didn’t come to pass, but we willed much of it into our own timeline anyway.

It really is an example of a superteam in which everyone is doing some of the best work of their career, isn’t it? There’s a really good episode of the Imaginary Worlds podcast about Syd Mead that discusses how Blade Runner and some of his other film work (he also worked on Tron, Aliens, Elysium and other science fiction films) was kind of an outlier. Mead’s career took off thanks to his work for corporate clients imagining sunny futures filled with, and partly created by, their products. The art he created on his own time is similarly optimistic. (Mead’s site is filled with examples.) Blade Runner looks like one of those futures gone wrong. Cronenweth bathes it in shadows and piercing rays of light. Vangelis, to my knowledge, never worked in this kind of foreboding mode before or after. Fancher and Peoples throw out much of Dick’s novel while still conveying many of its central themes. Ridley Scott, I’m just going say it: pretty good director.

I suspect I’m not the first to consider this, but let me throw out a read on this film to see what you think: Roy Batty is, if not the hero of this movie, its most complex, and in many ways, most human character. Sure, he’s a murderer, but he’s also capable of regret. If, as we’re told, part of what sets his generation of replicants apart from their predecessors is the ability to develop emotions, it’s in Roy that we most see this ability. He clearly feels for Pris. His attack on his creator stirs all sorts of complicated feelings inside his circuitry. His final moments find him fighting with Deckard while also finding a kind of peace at the prospect of his imminent death. If science fiction movies have a “to be or not to be,” it’s Roy’s “tears in the rain” monologue. I think the film ends with Deckard—replicant or not—just taking the first steps on the path Roy has already traveled. (“It’s too bad she won’t live. But then again, who does?”)

I don’t want to minimize the importance of Deckard or Rachael to the film, of course. And, on that front, there’s a scene we have to talk about, the one where Deckard stops Rachael from fleeing and takes her in his arms despite her protests. How would you describe this scene? The music suggests Deckard, and maybe Rachael, are overwhelmed by passion, but the use seems ironic given that Deckard is a character who kills replicants and now seems to be subjecting one to violence of a different sort. Maybe Deckard is feeling something like passion. Maybe he just feels like he’s using a piece of machinery. Whichever the case, Rachael submits but never offers consent. I’ve seen it described as a rape scene and I’m hard pressed to think of another way to talk about what happens (or what we can safely assume happens after the film cuts away) based on the moments leading up to it, even without the replicant issues. But even thinking a replicant can offer consent answers the question of whether or not we grant them humanity, doesn’t it? And if Deckard is also a replicant, what, if anything, does that change about this moment? I’ll toss these hot potato questions over to you, Scott.

Scott: Ouch, Keith! Ouch! I’m typing with scorched hands. I feel like the scene you describe above between Rachael and Deckard has been given extra scrutiny of late, perhaps in connection with the #MeToo movement and our more enlightened (hopefully) understanding of consent. Let’s keep in mind that Revenge of the Nerds came out two years after Blade Runner, and we can say now—as critics did not appear to say then—that our hero bedding a young woman by disguising himself as her boyfriend was definitely rape. (Though, to be fair, critics were distracted by the odious racism and misogyny throughout that film.) Blade Runner is at least more ambiguous—and I’ll make my attempt to unpack it below—but it’s worth reexamining these types of moments, if only to get a barometer on the culture at the time.

Sometimes I find myself thinking, “WWPVD: What would Paul Verhoeven do?” If you’re the type of person to imagine humanity at its worst, when the rules of society and morality are thrown out the window and people are free to explore their worst impulses (or “basic instinct,” if you like), what does that look like? And what rules apply when you’re dealing with a being you know is not human? Then there’s the specific issue here of Deckard having intense feelings for Rachael that are difficult to sort out, especially when he may or may not be a replicant himself. It’s part of the noir genre that Blade Runner is toying with here that rough play between men and women is a common feature, though the times allow it to be rougher than usual. Of course, there’s no getting around the fact that Deckard traps Rachael in his apartment and forcibly kisses her, suggesting as you say where things go from there. At the same time, I think it’s a deliberate effort on the film’s part to encourage the audience to step back and consider our feelings about Deckard, whose ruthless mission to kill replicants doesn’t exactly make him Indiana Jones. It’s a terrible, soul-coarsening labor that has turned him into a loner, and he cannot process the emotions that he feels for Rachael—a passion that expresses longing and hostility in roughly equal measure.

Which brings me naturally to a good point you make about Roy Batty being the most “human” of the characters in the movie. (I’m reminded of a favorite line from a middling Season Nine episode of The Simpsons where a robot on fire comes out screaming, “Why? Why was I programmed to feel pain?”) Though we definitely get a scary first impression of the replicants when Leon stops his testing short in the beginning, there’s this slow evolution throughout the film where the non-humans start to grow more complex in our estimation. You can see it a little in Pris, who may seem manipulative and freakish while trying to trick J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson) or attack Deckard, but also gives off a sense of childlike vulnerability, too. By the time we get to that final confrontation with Batty, I think the film has already primed us to feel differently about him and other replicants than we might have before.

In fact, it’s interesting to me that we don’t align ourselves with the replicants from the start, especially after reading the titles in the beginning that tell us how they were used for off-world slave labor. However artificial they might be, with their non-organic creation and limited shelf life, it shouldn’t take such a massive cognitive leap to imagine that a replicant with superior strength and agility can outpace humans in emotional intelligence, too. And once you concede that, how can you not sympathize with their rebellion? Or not be moved by Batty’s enlightened sense of perspective on himself and the plight of humans (of human-like beings) he displays? His evolution also means that Blade Runner can evolve into a film that’s about memory, history, mortality, and other subjects that arise out of the replicants being more complex than we might have assumed.

I am the writer and curator of the Ridley Scott Ranked feature on Vulture, and I know I’ve griped to you about the assignment, mainly because I felt (and still feel) like Scott’s first three films are his best. (Though I think more recent work like The Counselor, The Martian and The Last Duel have proven there’s still some gas left in the tank.) I can say that Blade Runner has looked better every time I watch it, nearly to the point where it could challenge Alien for that #1 spot. I think you have it right that Scott excels when his collaborators are allowed to do their best work, too, which can be an underrated skill when you talk about movies strictly in terms of their director. There are a lot of individual contributions here that are worth unpacking all on their own—I think, for example, that David Peeples is one of his generation’s most talented screenwriters, and that his Unforgiven is Chinatown-level perfection—but credit Scott as the guy making a big sum out of those parts.

Next up, we’re headed back to the silent era for Sherlock, Jr., the second Buster Keaton film in the Top 100. (We covered The General way back at #95.) That’s a comedy that’s meant so much to both of us that we included an image from it when we were first pitching the public on The Reveal. So if you’re expecting a contrarian take, look elsewhere.

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59: Sans Soleil

#54 (tie): The Apartment

#54 (tie): Battleship Potemkin

Discussion