#54 (tie): ‘Contempt’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

In his 1963 classic, Jean-Luc Godard puts a failing marriage and a troubled production in front of a CinemaScope hall of mirrors.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Contempt (1963)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

Ranking: #54 (tie)

Previous ranking: #23 (2012), #23 (2002), #36 (1992).

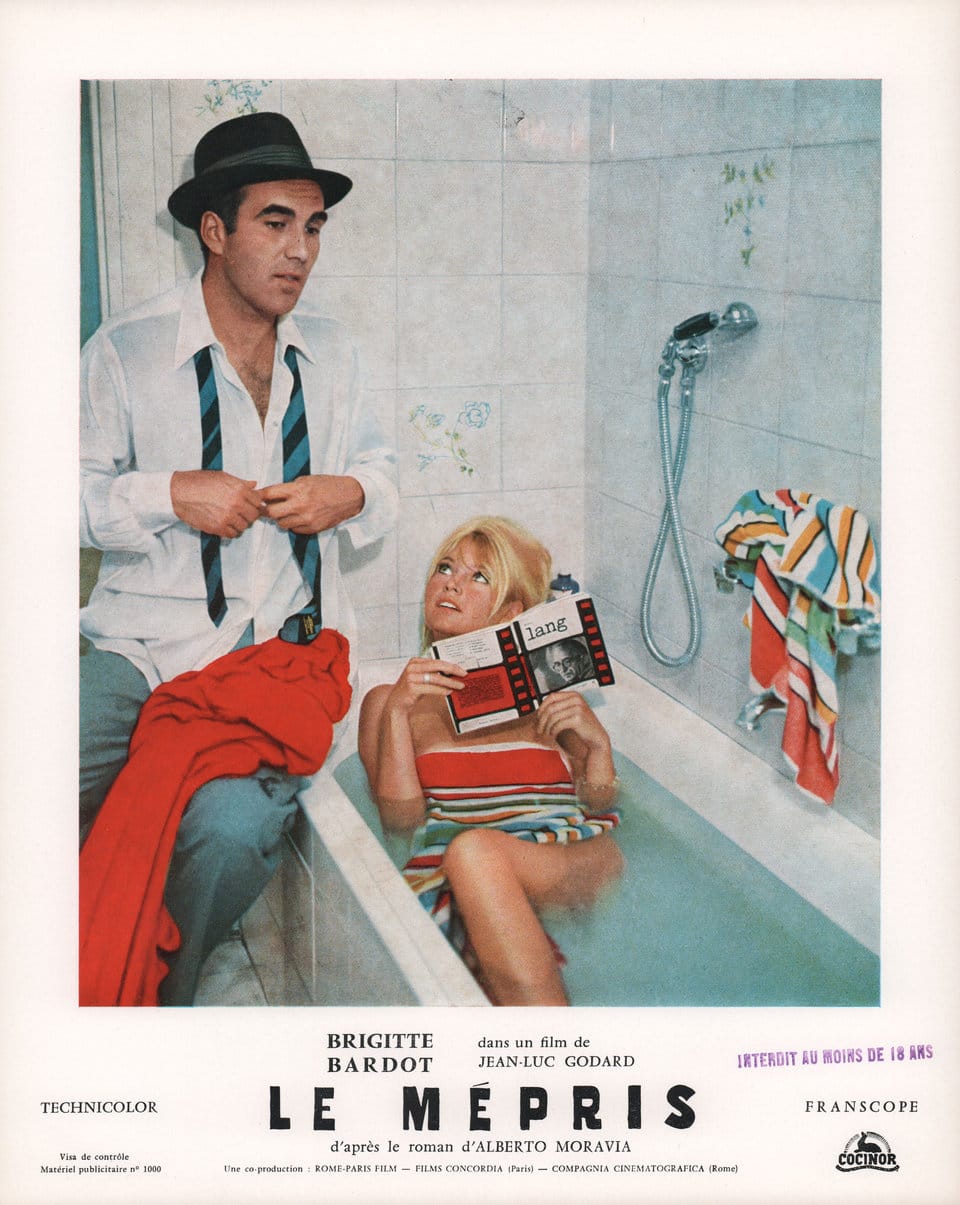

Premise: At the famed Cinecittà studio in Rome, boorish American producer Jerry Prokosch (Jack Palance) is trying to complete shooting on a screen adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey, but he’s in conflict with his director, Fritz Lang (playing himself), and wants someone to rework the script. To that end, Prokosch hires French playwright Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli), who occupies a nearby flat with his glamorous wife Camille (Brigitte Bardot). When Prokosch starts flirting shamelessly with Camille—and Paul, in turn, flirts with Prokosch’s secretary Francesca (Giorgia Moll)—it exposes a rift in Paul and Camille’s marriage that widens during an epic domestic spat.

Scott: Back when Jean-Luc Godard died in mid-September 2022, I chose to write about Contempt as a tribute to his irascible artistry, which I suppose gives me a leg up on this discussion, though I feel like my relationship with Contempt (and many Godard films) tends to shift every time I watch it. Following Pierrot le Fou and Histoire(s) du Cinéma, this is our third Godard conversation on the Sight and Sound list, with only Breathless still to come, and the four films certainly give you a range of different experiences you can have with him. At the time Contempt was produced, Godard was in the middle of his creative prime, turning out two or three films a year and leading the French New Wave to global prominence. But with respect to the formal restlessness and rebellious qualities of his earliest work, it seems to me that the film is the earliest example of Godard leaning into his pissy iconoclasm. Given the opportunity to bite the hand that feeds him, he chomped down lustily on not only his American co-producer, but the ostensible desires of his audience.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

How receptive are you to this film, Keith? I’m a great admirer of it, though I’ll also confess to finding it a bit glib and uncharacteristically blunt at times, due perhaps to the film being conventional by his standards. It has a distinct three-act structure, albeit notably oblong: The first act is set in Cinecittà and the third in Capri, each following the production of this troubled Fritz Lang adaptation of The Odyssey, while the second act, in which Paul and Camille fight in their apartment, takes up about as much running time as the bookends put together. There’s nothing particularly mysterious about the conflicts at play on set or within Paul and Camille’s marriage, though I think both arenas are compelling and clearly defined. Yet what sets Contempt apart—and maybe this is where an accusation like “glib” might apply—is how all of it seems to take place in quotation marks, with the audience always keenly aware that they’re watching a movie and that its director is out there mediating the experience.

The quotation marks are set by the incredible opening shot, in which a static camera sits at the end of a long dolly track at the studio while a crew shoots a take off in the distance. (Perhaps we’re supposed to feel a little envious that the future audience for this film-within-a-film will get that beautiful tracking shot while we’re stuck gawking in the distance, though Raoul Coutard’s exquisite framing says otherwise.) As the scene unfolds, a narrator dictates the opening credits to us (“It’s a film by Jean-Luc Godard,” “the unit managers are…,” etc.), which again calls attention to an obligation that doesn’t usually figure into the fabric of an actual movie. I’d argue that Paul and Camille’s relationship feels “real” in a way the rest of the film doesn’t, but there’s no escaping the metatextual prism through which we watch Contempt. Of all the movies about making movies, Godard’s is about as unromantic about the process as it gets.

The behind-the-scenes story about how Godard came to adapt Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo (English title: A Ghost at Noon) for Italian producer Carlo Ponti includes a number of juicy details on the casting—Godard wanted Kim Novak and Frank Sinatra for the leads, which scrambles the brain to consider—but settling on the luscious Brigitte Bardot, who gobbled up a solid chunk of the production budget, seems to have determined the direction the film would go. The American co-producer on Contempt, Joseph E. Levine, reportedly pushed for Bardot due to her exploitable body and Godard acquiesces with a first appearance that could be labeled “malicious compliance.” With Bardot’s Camille sprawled out naked on her stomach across her marital bed, Godard presents an inane post-coital scene with Paul that has her asking him about her various body parts (“See my behind in the mirror? Do you think I have a cute ass?”) while the camera goes out of its way to objectify her. It’s a middle finger to the whole commercial affair, and certainly not the last time Godard will raise it.

The casting of Jack Palance as Prokosch is Godard’s nastiest satirical touch, especially when set against Fritz Lang, a true film artist, appearing as himself. Prokosch is an arrogant numbskull who’s nonetheless accustomed to getting his way through a combination of bluster and money. He has convinced himself that only a German could direct his movie, but the German he hired keeps showing him dailies that confound him and have him searching for answers, which is how Paul gets a patch-up job that will help pay off he and Camille’s flat in Rome. Prokosch fancies himself just enough of an intellectual to try to impress Paul by handing him a picture book of Roman art for inspiration and by occasionally reading famous quotes from a tiny book he keeps tucked in his shirt pocket. From Godard’s vantage, it’s not surprising that an oaf like Prokosch, with his American bravado and his slick red two-seater, might feel he has access to a married woman like Camille, who he courts shamelessly in front of Paul.

I think it’s worth noting that Prokosch never actually gets what he wants, which may reflect Godard’s victory over Levine, who didn’t get a screen credit for his work on the film. But I’m curious to hear how Godard’s jaundiced perspective plays for you, Keith. The contradictions of it for me are embedded in Lang’s line about CinemaScope: “It’s only good for snakes and funerals.” It’s implied that Godard agrees with Lang on this point—I can’t find any evidence that he ever shot in 2:35-1 again, though he loved to experiment with aspect ratios—but Coutard’s widescreen compositions are so magnificent in Contempt, especially in that long middle section at the apartment, when the movement within the frame is so important. But I’ll leave that part of the film for you to start on, Keith.

Keith: Is there a term to describe when the compliance is malicious but the results are extraordinary anyway? Whatever Godard’s true feelings about CinemaScope, Contempt doubles as a kind of master class in how to employ it. And not just in the expected ways, either. CinemaScope is perfect for vistas and battle scenes—it was practically designed for such images—but Godard and Coutard prove it can be just as useful in depicting how the space between two people in the apartment they share can feel cavernous and how crossing it can feel like an act that requires extraordinary effort. A few shots here make playful/sadistic use of the widescreen frame. The slow pans back and forth sometimes feel like they’re intentionally there to induce seasickness, but mostly it’s used to remarkable effect. I keep thinking about the overhead shot in which Bardot disappears down a flight of steps descending into sea, throws her robe into the frame, then next appears below in the ocean.

To get back to your first question, how receptive am I to this film? Now, remarkably so. It’s one of my favorite Godard films, though I’m not sure I’d seen it since it was re-released in 1997. And, like a lot of Godard films, I wasn’t sure what to make of it at the time. I liked it but if you’d asked me at the time, I probably would have said something about how that mid-film fight scene goes on forever, not really getting that the scene going on forever, long past the point where other movies would have cut it off, was the point. I also probably would have missed the way the scene climbs and falls as the couple works through a bunch of conflicting, overlapping emotions or that the rhythm is intentionally off. Already a hard-to-like character, Paul strikes Camille early in the fight, an unforgivable gesture that would ordinarily bring such a scene to its climax. Instead, we have to keep watching as the fight goes on and on.

You bring up another contradiction. Yes, Contempt is a film that constantly makes us aware of quotation marks but this middle section feels real and raw. Not to bring in a dreaded extratextual detail, but Godard made this film without his wife and regular co-star Anna Karina. Though Karina would dismiss the assertion that the film was about their relationship, it’s hard to ignore Piccoli’s resemblance to Godard or the Karina-like wig Bardot dons in the scene. At the very least, Godard is teasing the audience with echoes of what they know of his life. That he would direct those echoes into a sometimes agonizingly intense scene of marital discord doesn’t feel confessional so much as, well, Godardian.

About those quotation marks: I sometimes wonder if Godard’s films resonate so widely with critics because, like so many of us, he’s someone who filtered his understanding of the world through film. Contempt is a movie about a break-up nested within the framework of a movie about moviemaking filled with nods to the process and to cinematic history. But these aren’t discrete elements. By the time Contempt arrives at one of my favorite shots, it’s become clear that Camille and Paul aren’t going to make it. The way Godard films the couple against the backdrop of a theater advertising Roberto Rosselini’s Journey to Italy, a film about marital strife with a miraculously moving conclusion, lends it poignancy, if you get the reference. Not that Godard cared if you got the reference or not. That said, no matter how many quotation marks Godard might want to place around George Delerue’s score, it keeps the film grounded in emotions that provide a counterbalance to self-awareness and distancing gestures.

Scott, does this film move you? It moves me while at the same time never letting me forget the stylistic games it’s playing or the meta-ness of Godard making a movie about a difficult collaboration between an artist and a commercial-minded producer while being in the midst of the same situation and calling attention to this at every moment. I’m also touched by Lang’s presence. He’d live until 1976, but his filmmaking career essentially ended a few years earlier with The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in 1960. But here he gets to embody the spirit of cinema for a disciple who’s skeptical about its future. Also, what do you think of Bardot? Then and now, she’s better known as a sex symbol than an actress (OK, now she might be best known for her horrible politics), but I find her touchingly vulnerable in this film.

Scott: I love the film’s treatment of Fritz Lang. Godard has no shortage of, well, contempt for many things in this film and beyond, but his admiration for Lang here is touchingly pure. In our very first scene with Lang, when they’re looking at dailies and Prokosch has a massive temper tantrum over what this insolent German has done with The Odyssey, the director looks completely unfazed. And why should he be? Imagine all the things that the real Fritz Lang has gone through. Here’s a filmmaker known for conjuring the darkest impulses of mankind in classics like M and Metropolis, someone who fled Nazi Germany for Paris in 1933, shortly after Goebbels expressed an interest in exploiting his talent. By the time he appeared in Contempt, as you say, he’d basically hung up his puffy directing pants. What’s striking about Lang playing himself here is that Prokosch’s tantrums have no impact on him whatsoever. He just winds up waiting his producer out, as if anticipating the deus ex machina car crash, and we get to see him continue shooting in Capri in the film’s final moments. He emerges from Contempt unscathed, with his dignity intact.

Perhaps there’s a personal statement here from Godard about how he, too, might manage the ebbs and flows of working in the film industry, where business concerns inevitably clash with an artist’s ambitions. However you feel about Godard, you certainly get the sense that he never cared to appease Prokosch types, except through the malicious compliance of objectifying Bardot as a bit of meta-humor. There’s a scene in Capri where all the major characters in a room together that I think is important to the film as a statement of purpose. At this point, Paul is having serious misgivings about his participation in the film and for working for a guy like Prokosch for the money. He talks about how’s really a playwright, not a filmmaker. Here’s the money quote:

“In today’s world, we have to accept what others want. Why does money matter so much in what we do, in what we are, in what we become? Even in our relationships with those we love?”

The idea of everything being transactional is a running theme of Contempt that finally surfaces explicitly here. So much of the conflict within Paul’s marriage with Camille comes down to insecurity and tension around money. It’s not as if Prokosch is particularly handsome or charming—with all due respect to Jack Palance, of course—but he has a red sports car and money to sink into this project while Paul is taking this job to pay off his unfinished flat in Rome. In his final scene with Camille, he seems to believe that their marriage will survive (or not) based on whether he compromises himself and writes for the money. I’m not sure that he’s completely correct to believe that—Camille, reasonably, does not think it’s fair to leave the decision to her—but it’s a tough predicament. Who can feel good about mucking with Fritz Lang’s vision?

As for what I think of Bardot in this film, I think she’s quite good, but I have mixed feelings about Camille as a character. I think her behavior comes across as immature and capricious at times, and you feel like Godard shares some of the hostility that Paul occasionally directs toward Camille. As you know, I have a tendency to dislike extratextual details when analyzing a film, which is to say anything that’s happened outside the frame (in the production, in an artist’s personal affairs, etc.) being relevant in talking about what’s in it. But Contempt makes that unavoidable, no? It’s meaningful to know about Godard’s breakup with Anna Karina, which you mention above, because it makes sense of the wig Camille dons at key points of the movie. It’s meaningful also to know about Godard’s clashes with producers on this very film, because they’re folded into the meta-text.

Contempt is such an unusual film because we toggle back and forth between being made aware we’re watching a film and being caught off-guard by scenes, especially in the second act, where the domestic discord seems authentic and straightforward by Godard’s standards. I have a lot of respect for it, but I confess that it can feel like an elusive object and it’s not as playful and fun as a lot of other Godard films of that era. Where do you see it fitting in his career, Keith? And are there any smaller moments that stand out as significant to you, too?

Keith: Maybe it’s that authentic depiction of discord that makes it a top-tier Godard for me. The tone of this sequence bleeds into the rest of the film, which has a lot of the playful, experimental elements expected of a Godard film from this era but lets them play out in an almost mournful key. When Contempt reaches the scene of Camille and Prokosch’s death—a grim scene that’s eerily similar to Jayne Mansfield’s death a few years later—it feels like the inevitable culmination of the tone set in the opening moments, which depict the filming of a movie scene with great somberness before pointing the camera directly at the audience. The film creates a sense of peril—physical and moral—to both the making and watching of movies. The latter half, the notion that surrendering yourself to someone else’s vision of the world for a few hours in the dark could leave you altered, maybe even marred, might seem like a silly idea on the face of it. But I think Godard takes it seriously. And I think anyone open to what Godard’s doing probably takes it seriously as well.

I get what you’re saying about Camille’s character. Whatever happens between Camille and Prokosch the first time Paul leaves his wife alone with the producer seems to poison their marriage. It’s easy enough to put together an idea of what transpires, but it still remains a blank the film never fully fills in, making the character feel a bit oversimplified. Paul, by comparison, feels more fully realized, but only up to a point. Why does he leave Camille and Prokosch alone in the first place? Does he know what will happen and sees it as inevitable—and maybe to his advantage? (I love Palance’s casting, by the way. He feels out of place in many ways, but I think that serves the movie. The baggage he brings as a heavy in Shane and other movies serves Godard’s film.)

At other moments, I find the visions we get of Lang’s Odyssey kind of haunting. We don’t see enough to get a full sense of what the movie looks like. It could be a masterpiece or a fiasco. But they’re powerful images that suggest a memorable film we’ll never see. (I was reminded of the scenes of the film-within-the-film glimpsed in Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, which play a bit like Antonioni parodies but also kind of overwhelm the movie in which they appear.) They’re ghosts of a movie never to be made, which feels apt for Contempt, a movie-haunted movie.

What’s next? Glad you asked. We’ve arrived at the first Chantal Ackerman to make the Sight & Sound’s top 100. But not the last. Join us in three weeks for a discussion of Ackerman’s 1976 film News from Home.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59: Sans Soleil

#54 (tie): The Apartment

#54 (tie): Battleship Potemkin

#54 (tie): Blade Runner

#54 (tie): Sherlock Jr.

Discussion