#54 (tie): ‘Sherlock Jr.’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

The movie magic of Buster Keaton.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

Dir. Buster Keaton

Ranking: #54 (tie)

Previous ranking: #59 (2012)

Premise: A small-town Projectionist (Buster Keaton) entertains ambitions of becoming a detective while courting The Girl (Kathryn McGuire). In this latter pursuit, he competes with The Local Sheik (Ward Crane), a dandy of dubious morals who frames the Projectionist after stealing a gold watch belonging to The Girl’s Father (Joe Keaton). Despondent, the Projectionist falls asleep on the job and dreams he’s part of the movie being shown, playing the part of the high-society detective Sherlock Jr.

Keith: If you know one thing about Sherlock Jr., it’s that it’s the one where Buster Keaton walks into the movie screen. What struck me watching the movie this time—and it’s a film I’ve seen quite a few times—is that it already feels like a great Keaton film even before that moment. One great gag follows another, each one expertly crafted without feeling mechanical. Take the stretch where the Projectionist finds a dollar while sweeping up in front of the theater then gives the much-needed bill to a crying elderly woman who shows up to look for it. Keaton brilliantly conveys a range of emotions without really changing his expression, then the situation escalates until the absurd conclusion when a big bruiser shows up and finds a wallet filled with cash.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

The film’s opening stretch also includes everything from the Projectionist tailing the Local Sheik at an absurdly close range and the great scene with the chase at the trainyard. It’s a neat survey of the different styles of comedy Keaton had mastered by this point. Turn Sherlock Jr. off before the film’s most famous moment and you’d still have a pretty idea of what Keaton was all about and what he did so well.

Still, it’s that innovation that really sets Sherlock Jr. apart. It also helps explain Sherlock Jr.’s ascent. Until 2012, The General was the consensus best Keaton film, the one that turned up on poll after poll. Now it’s all the way down at #95. I think Sherlock Jr.’s appeal to post-modern sensibilities partly explains that. But is that enough? Let me start by throwing that question to you. Keaton was turning out one great film after another during this stretch of his career. Why is this the one that’s broken out of the pack and not, say, Seven Chances or Our Hospitality? Is the walking-into-the-screen device that good?

Scott: I’d explain the ascent of Sherlock Jr. in a few ways. First, I think Keaton’s reputation with critics has skyrocketed, sparked by a series of box sets that Kino put out in the mid-1990s. Speaking personally, I had only a minimal awareness of Keaton because The General seemed to be the one film of his that was considered canonical. Once I dug into that box, he immediately became my favorite silent comedian, with that famous stone–faced expression and the derring-do of his stunt work, all tied to an impeccable sense of timing and film craft. The General stood out for so long for the sheer scope of Keaton’s achievement, given how much investment that film puts into realizing its historical backdrop. But once you look at Keaton’s other, smaller films, you can see something like Sherlock Jr. as more representative of his ingenuity in staging, effects, and deft physical comedy.

But let’s face it: Sherlock Jr. is more beloved than other comparably great Keaton works—I’m fond of The Navigator and College myself—because it’s about the thing we love the most: The movies. I’ve said this many times before, but the act of running a film through a projector at 24 frames-per-second and having these still images come alive as moving pictures is a magic trick. Having been a projectionist myself for many years, I can attest to many hours just staring at celluloid running through the gate and seeing this tiny moving image grow larger as it hits the projection-booth window and travels all the way to the theater screen. Fantasizing around that magic trick is a big part of going to the movies—or it was, anyway, before digital projection came along—and for Keaton to build Sherlock Jr. around an actual Projectionist is like tapping directly into the source.

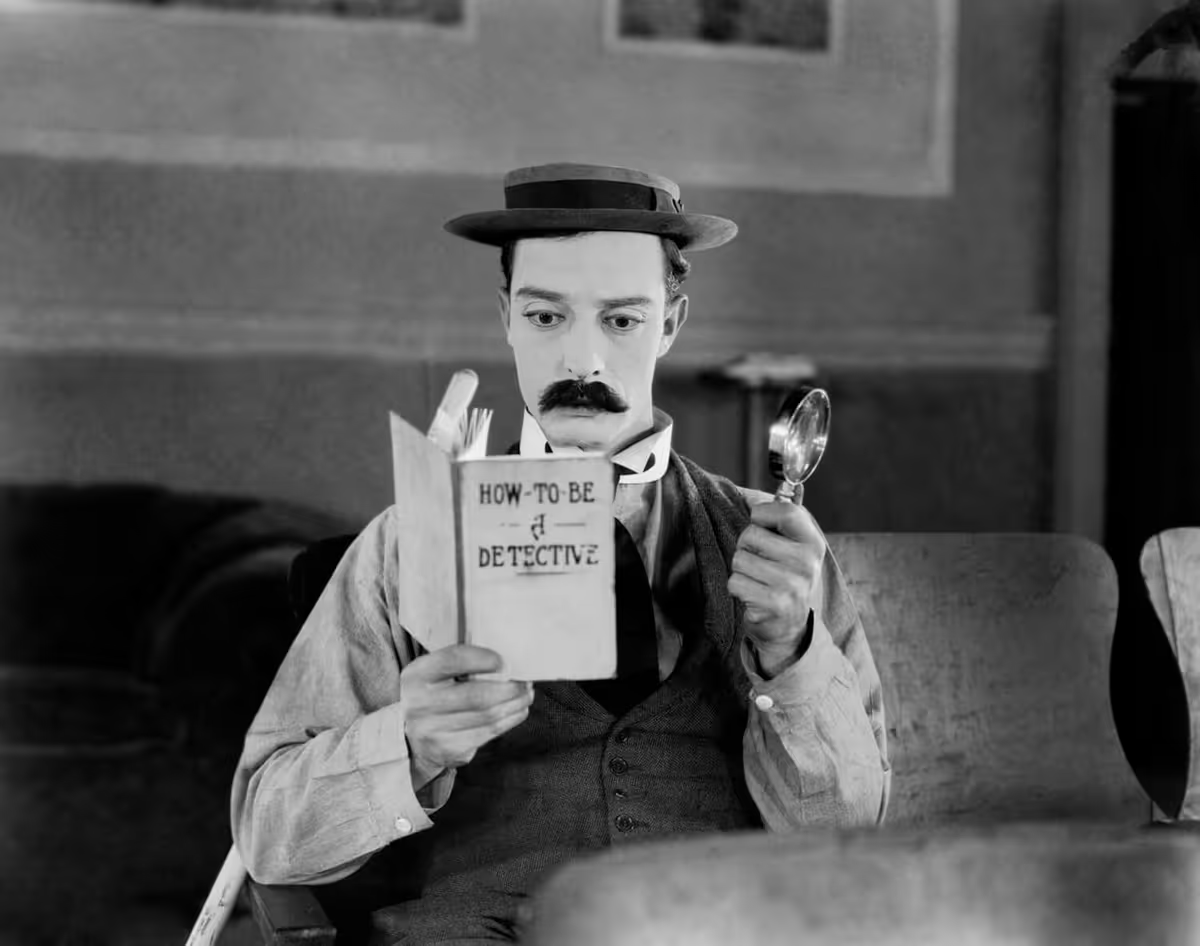

That said, I think you’re right to assert that this is top-drawer Keaton before we ever get to the going-inside-the-movie part. There are some many wonderful bits of business in that early section: The Projectionist examining his own fingerprint with a magnifying glass on his copy of How To Be A Detective as he sits next to a huge pile of theater trash; the sequence you mentioned about the dollars (and wallet) that are discovered within a second pile of trash (I love Keaton asking patrons to describe their missing dollar as if it were missing loved one); and, of course, the Projectionist’s hilariously literal interpretation of “Shadow Your Man Closely.” That last one offers several particularly deft moments, like the Projectionist catching the Sheik’s discarded cigarette midair and smoking it, or the stunt where he escapes the moving train by clinging to the water tank.

Before getting to the movie-within-the-movie stuff, though, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the Projectionist’s moral integrity in this situation. Let us keep in mind a few things: He desperately wants to have the three dollars he needs to buy The Girl a large, artfully designed box of chocolates from the confectioner next door, but he only has two bucks, which will just get him the pitiful $1 box. We then get to the sequence where he finds the third dollar in the trash pile (woo-hoo!) before having patron after patron coming back to him in search of their lost ones.

All he has left is a buck, which he uses to buy the small box, but then he tries to make it look more impressive to The Girl by changing the price on the box from $1 to $4, which happens to be the amount of money that the Sheik gets from the pawn shop for the stolen stopwatch. When the Sheik plants the receipt on The Projectionist, the $4 figure is all the more incriminating. (It’s touching that The Girl has enough faith in The Projectionist to follow up later, that’s another discussion.) In any case, it’s interesting to me that Keaton allows his hero to slip up in this small way when he could have easily been unimpeachably moral in the face of the Sheik’s villainy. I guess my one explanation is that Keaton is saying something about The Projectionist’s embarrassment over not having money. He’s a man trying to woo a woman well above his social station and fudging the numbers on a box of chocolates seems to him a necessary face-saving gesture.

But how could we not love this guy? And how could we not be wowed by his daydreaming fantasy of literally walking into a screening of “Hearts & Pearls” and cracking a similar case as a dapper and highly respected detective. What makes the movie-within-a-movie part of Sherlock Jr. so special, Keith? And what do you see as the film’s lasting influence on future movies that have attempted something similar?

Keith: I think that ethical lapse touches on something key to Keaton’s screen persona. He plays the good guy but good doesn’t mean perfect. He’s peevish and occasionally tempted to do the wrong thing. He’s easily distracted. But he’s never jerk enough to lose our sympathies. If anything, his shortcomings make him an even more relatable Everyman. And, if nothing else, he tends to be surrounded by actual jerks who make him look great in comparison. He may have his faults but he’s not the Local Sheik, either.

When we talk about the movie-within-the-movie section of Sherlock Jr., I think we’re really talking about two discrete segments. There’s the part where The Projectionist first walks into the movie, which then shifts radically between locations and genres. Then there’s the much longer part where The Projectionist becomes a part of the mystery movie in progress.

Let’s talk about the first part first. I’ve seen this movie many times and read about how it was made. (Here’s as good a place as any to plug our friend Dana Stevens’ excellent book Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century.) At the same time, when I watch this section, it plays like, for want of a less worn-out term, movie magic. He walks right into the screen and enters a world filled with wild animals and other perils. It’s exciting! It also raises the possibility that the world between the movie world and our world might be semi-permeable and you can see the influence of that idea all over the place, starting with the animated shorts that would soon have their golden age.

As for the second section, it’s wonderful but at heart not that different from other Keaton films that would set him loose in a variety of different genres. Like the opening section, it’s top-notch Keaton, but it’s the framing device that really sets it apart. When The Projectionist wakes up to find himself exonerated and in the arms of the woman he loves, it’s quite moving. And then he brilliantly undercuts it a little with the gag about The Projectionist starting to second guess everything when confronted with the possibility of parenthood. What a picture, right?

Scott, I don’t want to move on without hearing your thoughts on the movie-within-the-movie device. Why does it work for you? And what’s your take on the detective story stretch?

Scott: The permeability of the movie screen is something that has always existed figuratively, of course, because it’s part of the illusion of these still frames coming to life at 24fps. When we are immersed in the action on a screen and extend our empathy and imagination towards these images and what they represent, we are entering the world that filmmakers have presented for us. It’s only one step from that feeling to actively imagining ourselves on screen, too, perhaps wondering what we might do in a given situation or dreaming about visiting some beautiful backdrop or participating in a grand adventure. I’m sure we’ve all had that feeling like The Projectionist where we nod off during a movie and our persistence of vision follows us into sleep, and the line between reality and fantasy blurs for a bit. (As I’ve gotten older, this has become my nightly routine.)

But I’m glad you’ve separated the two sections where The Projectionist engages with the movie-within-the-movie, because the first of those sections is obviously the most audacious and abstract. While the action in “Hearts and Pearls” eventually becomes an upscale version of what’s happening to The Projectionist off-screen, only with him getting to star as the dapper and highly respected “Sherlock Jr.,” Keaton does use this first opportunity to show us what the movies (and what he) can do. As he tumbles through various backdrops—from a city street to a mountain cliff to lions in the forest to a desert train that nearly runs him over, etc.—it’s a compact assertion that there really are no rules about where the movies can take us. We are just an edit away from being whisked to wherever he (or another filmmaker) chooses to take us.

At the same time, Keaton uses the opportunity to show off his unparalleled physical gifts. Because even as the backdrop changes, there’s the continuity of The Projectionist in the center of the frame, having to balance himself and react to whatever new threat is bearing down on him. It’s remarkable how this montage acts just like another obstacle that Keaton, as a stuntman, has to navigate, as if it were a waterfall or a falling house. He turns an illusion into a physical presence.

Beyond all that, the movie-within-the-movie scenes also just have delightful comic nonsense in them, particularly the efforts of The Villain and The Butler to disrupt Keaton’s detective with foiled acts of deadly sabotage. My favorite of these is the exploding 13-ball that they set up during a friendly game of pool. I love how swiftly our hero makes his way through the entire rack without ever hitting the 13 yet when it’s time to hit a simple, straightforward shot of this last ball in the corner pocket, he shanks it completely. The 13 then resurfaces during the closing chase sequence, where it proves quite effective as a grenade. I’m also fond of the costume tucked into a hoop-sized covering in such a way that he comes out in a fresh disguise by jumping through it. Movie magic!

We are not quite done with silent comedies for this project—Charlie Chaplin’s heartbreaking City Lights, at #36, will come up at some point in 2026 for us!— but we are going to make a graceful, Buster Keaton-esque transition ourselves in a few weeks with Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, which also features a movie-within-a-movie, albeit one that’s fraught in a much different way. I’d end by noting that it’s good to get a few laughs out of this project when we can, because by my count, the Sight and Sound Top 100 only has six comedies—two by Keaton, two by Chaplin, The Apartment and Playtime. Respect for the genre remains hard to come by.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59: Sans Soleil

#54 (tie): The Apartment

#54 (tie): Battleship Potemkin

#54 (tie): Blade Runner

Discussion