#54 (tie): ‘The Apartment’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Rocketing from the 120s into the 50s, Billy Wilder's classic comedy starring Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine is one of the biggest movers on the latest Sight & Sound poll.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

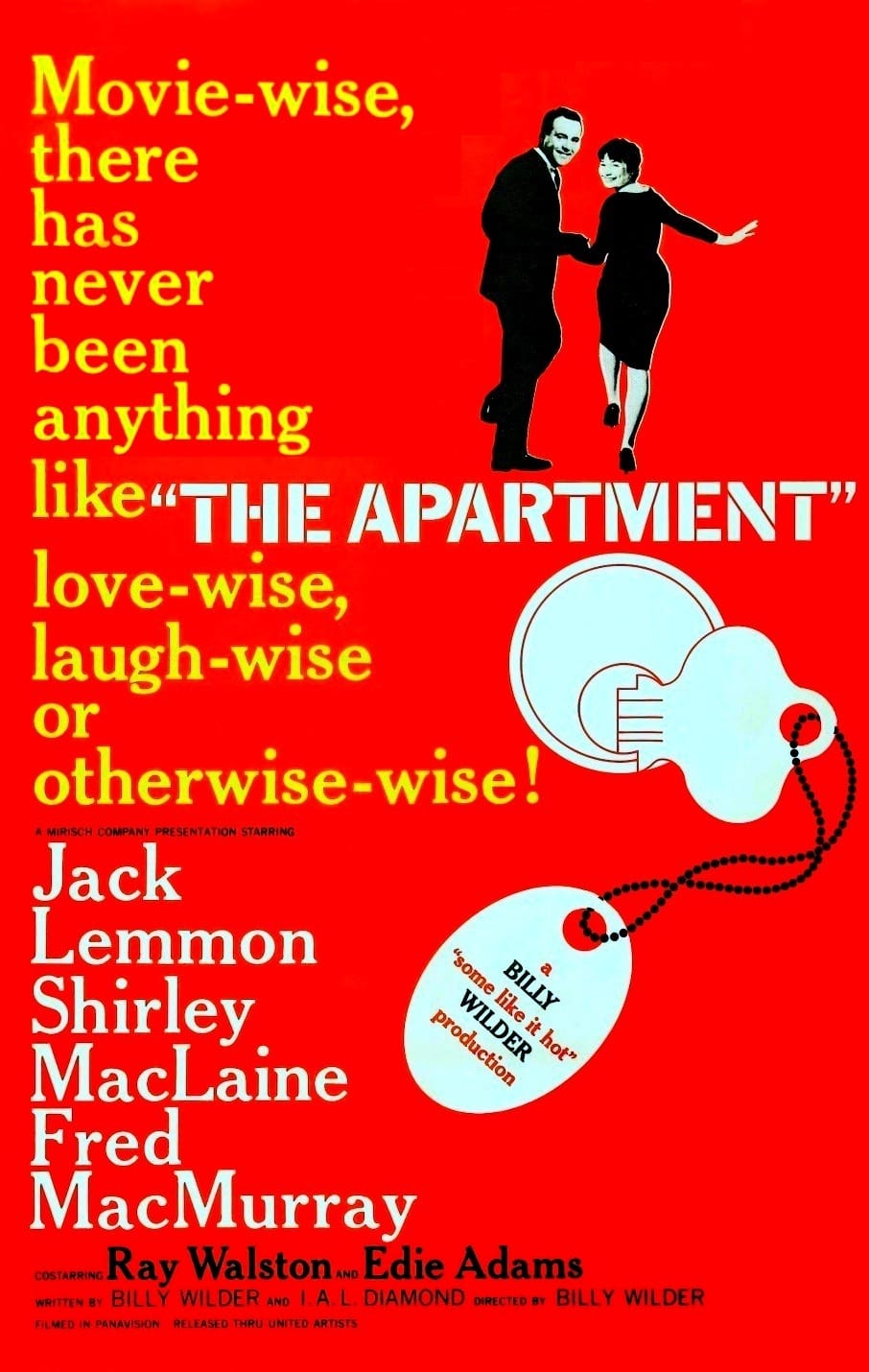

The Apartment (1960)

Dir. Billy Wilder

Ranking: #54 (tie)

Previous ranking: #141 (2012).

Premise: An ambitious office drone at a large insurance company in New York City, C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) allows four company executives to use his Upper West Side apartment to entertain their mistresses after hours, with the promise that they’ll give him a leg up on the corporate ladder. Baxter gets his wish when the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray), gives him his promotion, though Sheldrake wants his own access to the place. The situation is complicated further when Baxter takes a romantic interest in elevator operator Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine) and is crestfallen to discover that Fran has been having an on-again/off-again relationship with Sheldrake. Naturally, his affection for Fran threatens to jeopardize this nascent advancement in his career.

Scott: Where do we even start with this wonderful movie, Keith? So many of the films on this Sight and Sound list have a history of troubling or alienating audiences, or being so far ahead of their time that even critics were slow to catch up with them. That’s not the case with The Apartment. Everyone loves The Apartment and has loved it since it was released in 1960 and cleaned up at the Oscars, winning five awards including Best Picture, Best Director for Billy Wilder, and Best Original Screenplay for Wilder and his great writing partner I.A.L. Diamond. And it seems notable to me that the film has only gained in appreciation over time, taking a significant leap in the Sight and Sound poll from #141 in 2012 to its cozy spot at #54 in 2022, where it sits among three Wilder films in the Top 100. (We covered Sunset Blvd. at #78 and have Some Like It Hot still to come at #38. It’s astonishing to me that a film as great and foundational as his noir classic Double Indemnity is currently on the outside looking in at #196. His best work really is that good.)

But let me start with Fran’s compact mirror, because everything about that one little prop blows me away every time I see The Apartment. First there’s just the elegance of the reveal. At this point in the movie, Baxter has secured his promotion to second assistant administrator, the most junior of junior executive positions that nonetheless gives him his own office with a beautiful view of both the city and the rows of functionaries he has left behind. But he hasn’t even sat down at his desk before the four executives who put him there come asking for favors and then Mr. Sheldrake turns up, too, asking for the key. We learn before Baxter does that Sheldrake’s mistress is Fran, and witness the sad spectacle of Fran standing up Baxter at The Music Man because she was meeting with Sheldrake, who’d given the tickets to Baxter to keep him out of his apartment. The next day, Baxter discreetly returns the compact mirror that was left at his place to Sheldrake, which we know belongs to Fran.

Cut to the extraordinary sequence of events at the Christmas party on Baxter’s floor, where an ebullient Baxter lures Fran away from her elevator job to join in the fun. He has forgiven her for standing him up, because he's a heartbreakingly decent and accommodating man. As Baxter is off getting drinks, Sheldrake’s nosy secretary, who’d seen her boss and Fran meeting surreptitiously at a Chinese restaurant, makes it clear to her that Sheldrake has burned through many such lovers, including her, by giving them the same song-and-dance about leaving his wife and kids. After Baxter leads a dejected Fran back to his office for some privacy, we get this wonderful bit of business where Baxter shows off his new $15 bowler hat and Fran, a heartbreakingly decent and accommodating woman, tells him she likes it. Then she gives him her compact mirror to see himself in the hat and now Baxter knows about Fran and Sheldrake, but Fran doesn’t know that he knows. That’s clever.

It’s also a prelude to the most devastating line in the movie, in reference to the broken mirror. “I like it that way,” Fran says. “It makes me look the way I feel.”

That’s just perfect writing and plotting. For this prop to carry that much significance in terms of who knows what and when is so clever, and then to also function as this symbolic “reflection” on Fran’s sense of self adds so much depth to the film. It also sends it in a radical new direction tonally: The Apartment is no longer just a screwball romantic comedy about Baxter frantically arranging his life around his bosses’ extracurricular activities and maybe finding some companionship for himself on the side. It now becomes a film about two characters in the depths of loneliness and despair, having to deal with the abundantly clear reality that they’re on the lowest rung of the social ladder and they have been humiliated and exploited for it. The promises Sheldrake had made to Fran are merely lines off a script he’s read for many other women he’s bedded. She’s nothing to him. And Baxter, who should probably know better, is certainly not going to be treated as an equal by the same executives who routinely lock him out of his own apartment.

I realize that in talking about this one pivotal piece of The Apartment, I’m putting a lot of emphasis on Wilder’s (and Diamond’s) abundant gifts as a screenwriter, but I want to make sure we give equal consideration to his direction, since that’s the one part of his game that tends to get debated among film scholars. To that end, just for starters, I always think first of Baxter’s workplace: Section W, Desk# 861 on a single floor of a building that houses so many employees (31,279, “more than the population of Natchez, Mississippi”) that the work hours for employees to keep from overwhelming the elevators. Who could feel special or even human in a place like this? And, when you look at poor Baxter in the middle of this sea of low-level humps, what does it say about the state of the workplace in general and the dissatisfaction that must be gripping so many people around him?

What do you think, Keith? What’s the first thing you remember when you think about The Apartment? Where do you put in Wilder’s filmography? And do you have any theories as to why the film might have taken such a big leap in the Sight and Sound poll between 2012 and 2022? Is it greater respect for Wilder or maybe something specifically resonant about this movie?

Keith: When I think of The Apartment, my mind immediately goes to the stretch of the film in which Fran and Baxter—his opening narration notes that most people call him “Bud,” and he’s “Bud” in the script but do we ever hear anyone call him by that name?—bond in Baxter’s apartment. These are two people who might never have gotten to know each other in any real way were it not for the extraordinary, and sad, circumstances that bring them together. Sure, she agreed to go to The Music Man with him, but even if Fran had shown up, I don’t know that they would have had a shot to develop any real sense of intimacy. It’s a big city and a big office and Fran’s not exactly in a position to focus on a relationship with the sweet guy who always takes his hat off in the elevator. But temporarily removed from the concerns of the world, they discover there’s no one they like better than one another.

With the proviso that there are some Wilder films I have yet to see—including at least one many hold in high esteem, Love in the Afternoon—I’d rank this quite high in the Wilder filmography. It’s funny: When I think of the quintessential Wilder film, I think of The Apartment, but it’s not exactly of a piece with, say, Double Indemnity or Stalag 17, is it? It’s sandwiched in Wilder’s filmography movies that are just as funny, if not funnier—Some Like it Hot and One, Two, Three—but there’s an intimacy to it that’s all its own. You rightly point out the cleverness of the screenplay and the brilliant use of Fran’s compact. In another film, that could feel like a gimmick. Instead, it’s heartbreaking because of the depth given these characters by the screenplay but also, of course, these two amazing performances.

As for why it’s leaped, I don’t really have a theory beyond it looking more and more like an ideal of a certain type of film. I guess we’re technically talking about a romantic comedy, but the stakes feel higher here. With most rom-coms, the worry is “Will these two people who obviously belong together get together in the end?” But Fran’s danger runs deeper. She’s on the edge of despair, a place Baxter knows well, and apparently knows how to leave behind. It has all the bubbly pleasures of the best rom-com, but the loneliness of these characters and their need to leave that loneliness behind feels more profound.

I think we touched on Wilder being underrated as a visual stylist when we covered Sunset Boulevard. The Apartment only strengthens that case. You mention the office scenes. Wilder accomplished the cavernous feel of Baxter’s workplace with some clever use of forced perspective but there’s also a neat contrast between the glaring lights of the insurance company with the dimness of Baxter’s apartment. I was also struck by an early scene in which Baxter watches from the shadows as one the execs and his date talk outside his apartment. What was on the page might have come first for Wilder, but what made it in the frame clearly mattered, too.

You refer to Baxter as “a heartbreakingly decent and accommodating man.” I don’t disagree, but I don’t think those qualities are entirely altruistic. Baxter loans his apartment out because he wants to get ahead, an approach that pays off over the course of the film. It also comes back to bite him, of course, but I think the Baxter of the film’s early scenes wants to become part of the male executive world while choosing to look past the exploitative elements of that world. Baxter doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would tear through a series of mistresses, but I don’t know that he necessarily sees others doing it as a problem as the film begins. The Apartment is about him coming to recognize the, well, shittiness of that behavior. He’s not the playboy his neighbors think him to be but he’s also not, to borrow Dr. Dreyfuss’ word, a mensch.

That’s how I see it anyway. Am I off? And if that’s Baxter’s journey, what do you see as Fran’s? Also, we’ve barely touched on the supporting cast, which is filled with memorable characters both at the office and at home. What stands out about them to you?

Scott: You’re right on Baxter, Keith. He doesn’t really strike you as a cynical guy, exactly, but Baxter does seem to realize that hard work alone isn’t going to deliver you from the sea of desks on the 19th floor to a private office with a key to the executive washroom. (What could be in that washroom, Keith? Probably too costly for an attendant, especially given the lock on the door, but I’d bet you’re wiping your hands on cloth towels.) We can only guess how Mr. Sheldrake and the four other executives who jerk Baxter around got their jobs, but given the chummy rapport they have together, it certainly feels like a network of corporate advancement that’s eternally inaccessible to outsiders like Baxter, whose facility with numbers suggests that he knows the business well.

At the same time, he’s not that far from being a mensch. He’s a buoyant and cheerful personality, and the fact that he’s the only man to remove his hat in Fran’s elevators does make him special, because he’s willing to show deference and respect. Those are qualities that work against him in the corporate rat race, and they also account for his willingness to let his bosses walk all over him. It matters that they’re all dangling a promotion at the end of a stick, but do you really think Baxter is the type of guy who would say “no” to something a superior asks him to do? He also displays tremendous nobility when it matters most, like protecting Fran by having his neighbors believe that he’s a reckless, insatiable “ladies’ man” or taking a punch from her brother-in-law. The sad part about his arrangement with his bosses is that he would have never gotten their mercy, much less their respect. Any gains come under the condition that he continues to provide the same service—and maybe even add some amenities while he’s at it.

(One random piece of brilliance from the screenplay while I’m thinking about it: In one scene, one of the bosses complains to Baxter having to take his date to the drive-in because his apartment wasn’t available. In a later scene, we overhear his girlfriend telling a confidant, “So I said to him, ‘Never again. You either get yourself a bigger car or a smaller girl.” A clever throwaway line you might have missed that pays off a set-up you might also have missed. What craft!)

As far as the supporting players go, I’ll start with Mr. Sheldrake, played by Fred MacMurray, who Wilder had also cast as an insurance man 16 years earlier in Double Indemnity. The MacMurray in Double Indemnity isn’t so dissimilar from Baxter in that he’s a working stiff who’s trying to find some short cut to get ahead, and I think we feel some sliver of sympathy for him, even though he’s part of a plot to murder a guy for a premium payout. Mr. Sheldrake’s offenses are common and nonviolent: He’s a womanizer who cheats on his wife and leaves a trail of broken hearts in his wake. But MacMurray turns him into a far more contemptible figure here, a man who doesn’t think twice about manipulating and exploiting anyone below him on the corporate food chain—which is to say, every character in the building. You hope that Fran can see through his act, especially when she comes back to him late in the film, but The Apartment is really smart about how success (or lack thereof) in the business world affects the way people think about themselves. If you’re made to feel worthless at the office, then you start to believe it. MacMurray carries himself with the delectably unctuous self-confidence of a man who knows he can get away with anything.

And obviously, we have to mention Jack Kruschen’s turn as Dr. Dreyfuss, which earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor, his lone bit of recognition in a 50-year career as a character actor for film and television. It’s a plum part for Kruschen, whose Dreyfuss introduces Baxter—and perhaps many non-Jews in the audience—to the importance of being a “mensch,” which for Dreyfuss starts with an extension of care and leniency toward Baxter in his situation, despite his understanding of him as the neighbor who’s making a racket all night. (“Would you mind leaving your body to the university?”) I think what’s so touching about Dreyfuss is not just that he’s a model of what it means to be a mensch, but that he wants Baxter and Fran to understand their value as people. And that can start by extending kindnesses to each other that are purely selfless.

One question I have for you, Keith: What’s the significance of Fran and Baxter being non-native New Yorkers? That’s one thing they have in common other than each attempting to take their own lives at one time or another. It seems to me that the city itself, represented by the headquarters of this massive insurance company, points toward a way of life that Wilder treats warily. How does being part of an organism that large affect the social order? We in the audience are assumed to be outsiders to this world, like our heroes. What impression does Wilder want to leave us with?

And, as a parting thought, what are the lines and moments that really stick out to you? Because there are many, aren’t there?

Keith: Scott, you didn’t note the sight gag that puts the bow on the running gag about the small-car, which the boss in question, Kirkeby (David Lewis) has explained he had to borrow from his nephew. Here’s how it appears in Wilder and Diamond’s script:

EXT. BROWNSTONE HOUSE - DAY

A Volkswagen draws up to the curb in front of the house.

Kirkeby gets out on the street side, Sylvia squeezes herself

out through the other door.

As for Fran and Baxter both being non-New Yorkers, I think it contributes to the film’s idea of New York being a place where misfits with dreams wash up. They are from, respectively, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, which aren’t exactly small towns. But the prints on Baxter’s walls—by Chagall and Mondrian among others—and the Ella Fitzgerald record in his collection establish him as a man of taste who wants to see beyond the boundaries of the place where he was born. It’s notable, too, that both he and Fran seemed to have fled difficult hometown situations for the possibilities offered by New York, where no one knows their names or anything about their pasts. The downside, of course, is that you can get lost in a place like that.

The upside is that, if you’re lucky, you find your people or your people find you, even if they don’t look or talk like you. Wilder and Diamond were both Jewish immigrants from, respectively, Germany and Romania. It feels apt that they drop Baxter in an apartment building that’s also home to Jewish immigrants who’ve done the hard work of carving out places for themselves in the city and are now extending a spirit of gratitude to their neighbors. (I’m making some, I think, safe assumptions about these characters’ backgrounds.) Charges of cynicism sometimes get leveled at Wilder, and sometimes that description feels apt for movies both good (Ace in the Hole) and deeply unpleasant (Kiss Me, Stupid). Cynicism is part of the mix in The Apartment, but characters like the Dreyfusses and Baxter’s landlady, Mrs. Lieberman (Frances Weintraub), provide a counterbalance that ultimately outweighs it. There may always be takers like Sheldrakes in the world, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t other sorts of people.

As for moments that have stuck with me, I think I was just as shocked as Fran when she hears the gunshot-like champagne pop as she approaches Baxter’s apartment. I also love the sequence where Baxter drunkenly picks up the drunken barfly Marge (Hope Holiday). Then there’s the final scene, which is as, well, perfect in its way as the “Nobody’s perfect” closing of Some Like it Hot. It’s so moving and romantic that it might take a moment to realize that these two people, who are obviously meant for each other, haven’t even kissed.

One more thing before we finish: We’d be remiss if we didn’t at least mention Promises, Promises, the Broadway musical adaptation of the film with a book by Neil Simon and songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Jill O’Hara and Jerry Orbach played Fran and Baxter in the original 1968 production. I’ve never seen it, but it certainly produced some great songs. Here’s Sean Hayes and Kristen Chenoweth, who appeared in a 2010 revival, performing one of them:

Next: Battleship Potemkin

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca|

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59 Sans Soleil

Discussion