Catching Up With the Critics (Pre-Summer Edition)

With blockbuster season upon us, it's a good time to check out the early-year gems that slipped under the radar.

We don’t see all the movies we want to here at Reveal headquarters. And we certainly don’t have the time to review everything, even if we had the time to see them. So we have to do what a lot of our readers presumably do: Keep an ear out for some of the less-ballyhooed gems we missed and try to squeeze as many of them into schedule as possible. I used to reserve that project for two-part, end-of-the-year round-up pieces about the highest-rated Metacritic movies I had not seen (2021: Part 1, Part 2; 2022: Part 1, Part 2; 2023: Part 1, Part 2) before switching gears last year and choosing instead to look at favorites from my most trusted film critics. That approach, dubbed “Catching Up with the Critics” (Part 1, Part 2) turned out to be much better, yielding four films that would make my Top 15 list, including two stunners in the top five, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s About Dry Grasses and Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

With the summer movie season officially kicking off next weekend, I thought it’d be a good idea to take stock of the (potentially) great films I missed in the first(ish) half of the year, if only to give us that much more binging time toward the end of the year. Of the five films sampled here, only one seems to have a solid chance of cracking the Top 15 if the year rounds into more or less “normal” form, but all of them are strong, arresting visions from independent distributors with moments that stick to the ribs. In no order:

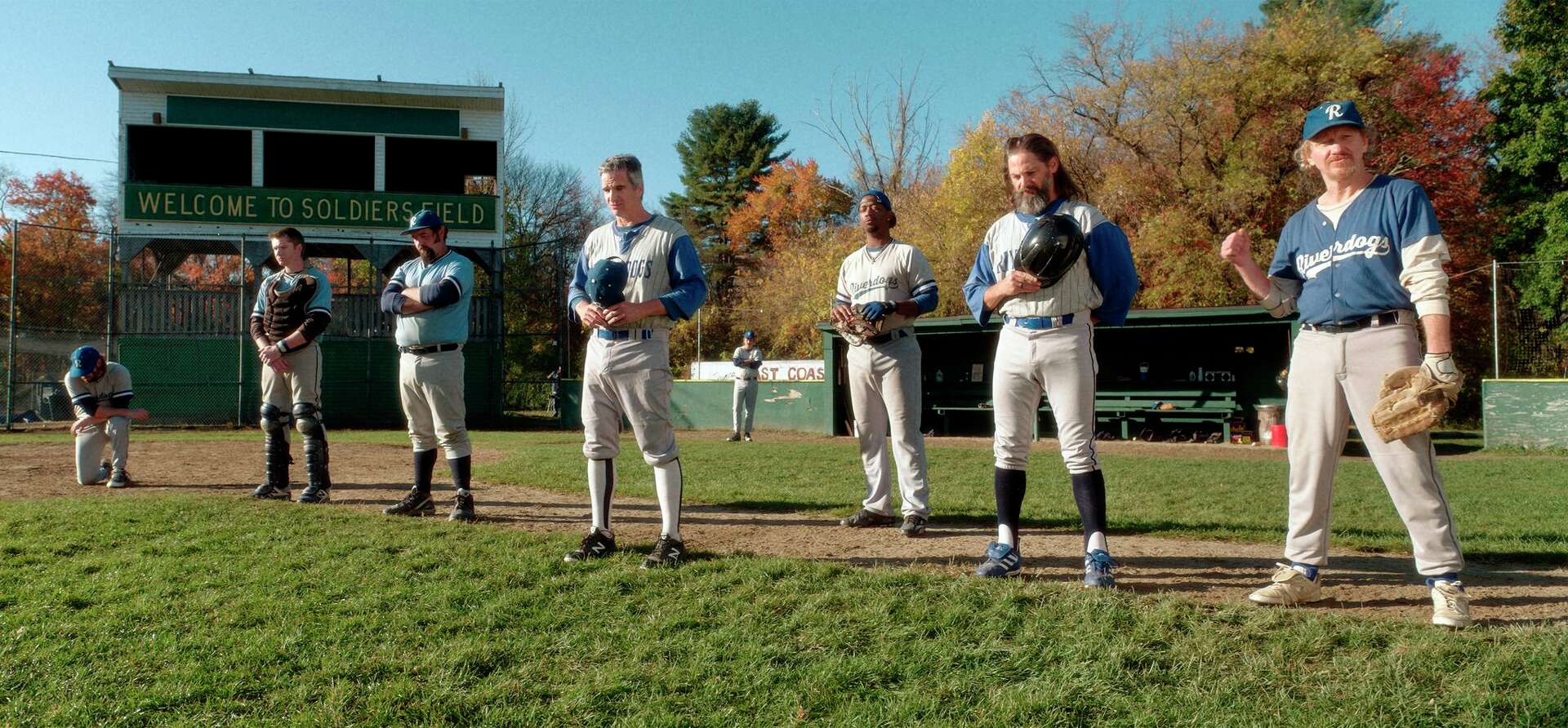

Eephus (dir. Carson Lund)

The critic: Keith Phipps, The Reveal

How to watch: Rentable on digital platforms

List-worthy?: Extremely honorable mention.

Premise: In small-town Massachusetts in the 1990s, two amateur baseball teams, Adler’s Paint and the Riverdogs, square off for the final game ever to be played in a stadium scheduled for demolition. With the pace slow and the stakes high, the teams battle it out in a close game that extends past sunset.

Keith’s thoughts: “There’s a tattered nobility to both teams grudgingly raging against the dying of the light, literal and otherwise. It’s a hang-out movie that doubles as an elegy for a way of life and those clinging to it until they can cling no more.”

My thoughts: Instantly one of the two or three greatest films ever made about baseball, like Field of Dreams for people (like me) who are more temperamentally inclined to love Bull Durham. There’s so much baseball-specific sentimentality attached to Eephus like barnacles: An attachment to the game and its laconic rhythms, the camaraderie that develops in a sport that unfolds over so much time and so many longueurs, the bottom-of-the-ninth significance that goes along with a final game played by middle-aged men who will never see this field (or any other) again. All of those sentiments are felt, perhaps a bit too heavily at times, but the “hang-out” qualities of Eephus consistently redeem it, along with its impeccable attention to certain offhand details, like the need to go rooting through the abutting woods for foul balls because you don’t have enough in reserve. For a movie about death in its myriad allegorical forms, it’s a special mercy for Eephus to be so throughly entertaining.

Misericordia (dir. Alain Guiraudie)

The critic: Wesley Morris, The New York Times

How to watch: In theaters. (Information here.)

List-worthy?: Yes.

Premise: When he returns to a tiny French village for the funeral of his former boss, a baker who’s died at the age of 62, Jérémie (Félix Kysyl) stays with the baker’s widow (Catherine Frot) and his son (Jean-Baptiste Durand), who’s extremely agitated by Jérémie’s presence. As the stay grows longer, the tension between Jérémie and the son over their past relationship intensifies into violence, and other men come into the picture, including an like-aged farmer (David Ayala) with imposing physicality and an aging pastor (Jacques Develay) whose sympathy toward Jérémie comes with an asterisk.

Wesley’s thoughts*: “‘Misericordia’ is film noir with the lights turned on. Even when its characters are working your nerves, it tickles. Guiraudie is playing those nerves like a harp.”

My thoughts: Guiraudie’s 2013 breakthrough film Stranger By the Lake remains a high watermark for queer cinema in the current century, an insinuating thriller (of sorts) that functioned both as a notably explicit portrait of a gay cruising scene and a peculiar deconstruction of the genre. The motives and actions of its characters are mysterious and unexpected, and Guiraudie’s interest in resolving the crime of passion at its center is more psychological than practical. While he’s taken a couple of left turns since then—his 2016 film Staying Vertical, a road picture about a filmmaker searching for material amid a wild set of circumstances, is almost heroically off-putting—Misericordia puts him squarely back in Stranger By the Lake territory again, as the morality of murder gets caught up in various crosscurrents of desire. As Jérémie, Kysyl roves around the movie like a honeytrap that seemingly every character falls into, despite the giant question mark that exists where his soul should reside. He’s maddeningly difficult to read but utterly compelling, which is also a good way to describe the film around him.

(* As their two-time Pulitzer winner, Wesley Morris has room to roam all over the Times’ culture pages, so when he decides to review a movie, which he’d done regularly for many years at the Boston Globe, it’s always an event.)

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (dir. Rungano Nyoni)

The critic: Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

How to watch: Rentable on digital platforms.

List-worthy?: Honorable mention.

Premise: While driving home from a party in her native Zambia, Shula (Susan Chardy) happens to come across the body of her Uncle Fred, which is splayed out dead on the road near a brothel. As loved ones gather in the family’s middle-class home to participate in mourning rituals, Fred’s history as a sexual predator, an open secret among many of them, colors the proceedings.

Manohla’s thoughts: “Rungano Nyoni, who was born in Zambia and grew up in Wales, knows how to make an entrance, and so does Shula. She’s a great character, and while her arresting introduction grabs you from the start, Shula keeps you tethered throughout. Hers is a story of discoveries both minor and monumental, one that’s flecked with troubling visions and an escalating sense of urgency.”

My thoughts: The entrance that Manohla refers to above is Shula discovering the body while dressed in party attire that includes a silver-sequined-speckled headpiece and a billowing black bodysuit that resembles Missy Elliott in the video for “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly).” It immediately establishes her as more cosmopolitan than her Zambian relatives, but she’s also more serious and enigmatic than her cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), who lets her own history of abuse at Fred’s hands spill out in a drunken rant. Shula commits some small acts of rebellion to express her feelings about the deceased—she shocks a group of visitors by bathing, which is ritually forbidden—but she also has to manage a family with major generational and gender-related fault-lines. Though Shula eventually asserts herself, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl stays by her side as navigates a difficult situation, which allows Nyoni (I Am Not a Witch) to explore a complex family dynamic and work in some unexpected comic notes, too. Mourning a monster isn’t any easier than mourning a saint, especially victims who have had to spend their young adulthoods bottling up their trauma.

The Ugly Stepsister (dir. Emilie Blichfeldt)

The critic: Bilge Ebiri, Vulture

How to watch: Shudder; in theaters; also digitally rentable.

List-worthy?: No. (But for horror fans, essential.)

Premise: In this twisted Norwegian take on Cinderella, the focus falls on Elvira (Lea Myren), the stepsister of the title, who’s on a desperate quest to marry the dashing prince (Isac Calmroth) after her mother’s new husband, who dies on their wedding night, turns out to be penniless. In an effort to defeat the deceased’s more naturally beautiful daughter Agnes (Thea Sofie Loch Naess), Elvira puts herself through finishing school and multiple cosmetic surgeries while Agnes is reduced to a common wench.

Bilge’s thoughts: “What makes Norwegian director Emilie Blichfeldt’s The Ugly Stepsister so powerful isn’t that it turns the tables on a classic fairy tale — frankly, I’m surprised it’s taken this long to get a movie sympathizing with Cinderella’s allegedly homely, dim-bulb stepsisters — but rather the way it does so, by placing us in a world of bleak, magically-inflected terror that underlines the base grotesquerie of the original.”

My thoughts: Cinderella by way of David Cronenberg and Todd Solondz, The Ugly Stepsister applies the visceral body horror of the former with the latter’s alignment with misfit types who are genuinely deplorable, if also oddly sympathetic in their plight. We can recoil at Elvira’s willingness to sabotage poor Agnes at every turn while understanding the existential pressures she’s facing and the lengths she’s willing to go to transform herself into a young woman worthy of a prince. (In these ye olde folk horror times, the perfect nose is achieved through a couple of excruciating whacks with a chisel and trimming the fat involves ingesting a tapeworm that eats what you eat—and then some.) That we know how Cinderella ends makes Elvira’s ordeal that much more painfully futile but also a little more human, given the universal desire that all people have for love and money. At a time when fractured fairy tales like Wicked, Maleficent and Cruella are having us rethink their villains without tarnishing the family-friendly brand, Blichfeldt’s nasty little treat goes full Grimm.

April (dir. Dea Kulumbegashvili)

The critic: Justin Chang, The New Yorker

How to watch: In limited release now.

List-worthy?: No.

Premise: In the country of Georgia, where abortions are severely restricted and stigmatized, Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili) secretly performs them in a rural village while excelling at her day job as a hospital obstetrician. But after a newborn dies shortly after delivery, it triggers a negligence investigation that threatens to expose Nina’s double life and destroy her career.

Justin’s thoughts: “This extraordinarily bleak and devastating work, set in a damp-looking stretch of eastern Georgia, shows us a simulated abortion, two unsimulated births—one vaginal, one C-section—and, for good measure, the administration of an epidural. Each of these scenes is shot in a single, static take—composed, by the cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan, in a nearly square aspect ratio—that refuses to look away until the procedure is finished. You’re reminded that the key to realism isn’t necessarily a convincing prosthetic or a well-timed spurt of blood; it’s the weight of time itself.”

My thoughts: The 21st century has brought us a surprising wealth of great, uncompromising films about abortion: Vera Drake, Happening, Never Rarely Sometimes Always, and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, just to name the most accomplished. April certainly covers the “uncompromising part,” given that it opens with an overhead long take of unsimulated child birth and doesn’t blink through Nina’s kitchen-table abortions, to say nothing of the occasional sketchy trysts she has with strange men to slake her gnawing loneliness and appetite for self-destruction. Greatness does elude April somewhat, however, due to the overdetermined artiness of Kulumbegashvili’s style, which favors extremely long takes (at a 1:33-1 aspect ratio) and other heavy touches, like the appearance of a naked, humanoid alien creature that wheezes on screen for purely metaphorical purposes. Yet there’s no denying the intensity of Nina’s experiences or the integrity that Kulumbegashvili lends to a life where she’s willing to suffer in order to alleviate the suffering of women who desperately need her. And to those previously mentioned abortion dramas, April adds another specific, vividly realized time and place to a global assault on women’s health care and the patriarchal terrors that menace doctors and patients alike.

Discussion