In Review: ‘Ella McCay,’ ‘Silent Night, Deadly Night’

James L Brooks returns with a curiously misshapen new comedy while a holiday-themed slasher remake overdelivers on low expectations.

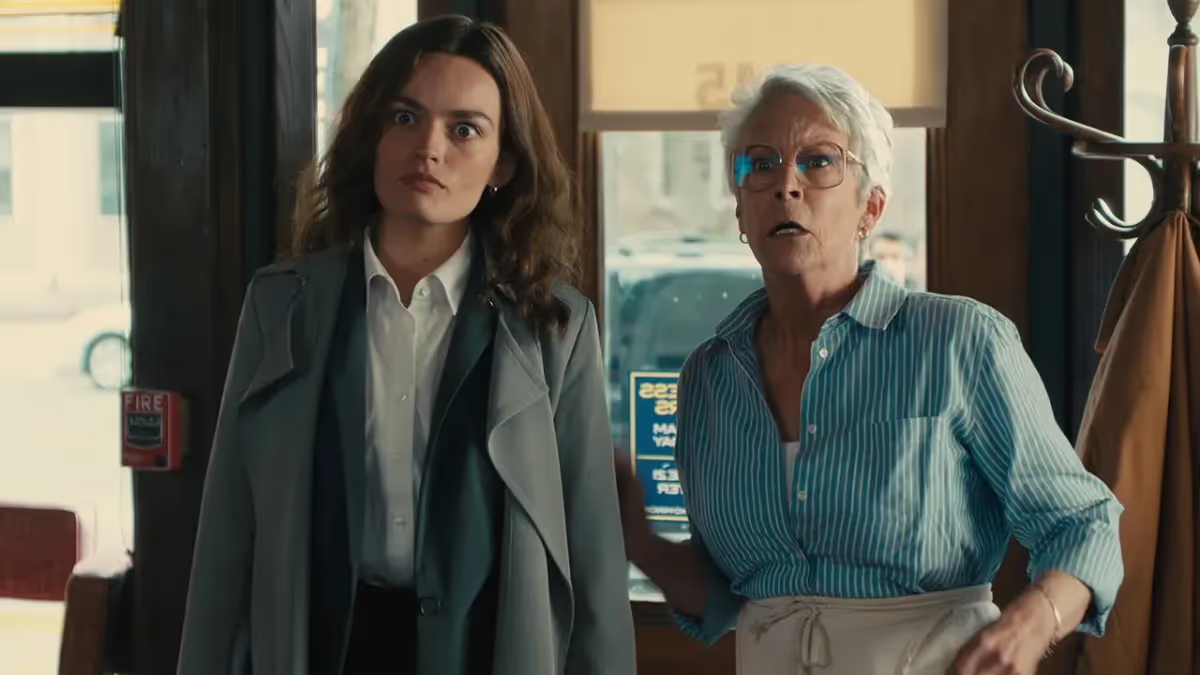

Ella McCay

Dir. James L. Brooks

115 min.

As Helen McCay (Jamie Lee Curtis) leaves to watch her niece Ella (Emma Mackey) leave to be inaugurated governor of the never-named (but East Coast-coded) state in which they live, she pauses on her way out the door to grab a tissue. Then, after waiting a beat, she grabs a few more. Then, as if finally realizing the momentousness of the occasion, she drops the whole box in her purse. It’s a great, perfectly executed gag of the sort Ella McCay writer James L. Brooks has been creating for years, both for television (where his credits include everything from The Mary Tyler Moore Show to The Simpsons) and film (Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News, and As Good as it Gets, to hit the high points). Ella McCay, Brooks’ first film since How Do You Know in 2010, is filled with classic Brooks elements like endearingly flawed characters, sharp one-liners, a deep concern with ethical questions, and lines of dialogue that cut to the heart of a given scene with devastating understatement. If only he’d figured out how all those pieces fit together.

The troubles begin almost immediately when Ella’s aide Estelle (Julie Kavner) announces she’ll be narrating the film, ushering in a long opening stretch that flashes between 2008, in the days just after Obama’s first presidential victory (where most of the film takes place)—and scenes in the past, when Ella made the decision to remain with Helen rather than relocating with the rest of her family after her philandering father Eddie (Woody Harrelson) is forced to resign from his job. The iffy de-aging effects are less of a problem than a ramshackle construction that makes it feel like the film will never get started. An even bigger problem: it never really does.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

Early in the film, Ella, a young lieutenant governor in 2008, reveals a potential scandal to Helen: a reporter has discovered that she and her husband Ryan (Jack Lowden) have been having afternoon “marital relations,” as she puts it, in an unused apartment located within the capital building. It’s seemingly the mildest possible scandal, but since it does violate state law, Ella has reason to worry about it blowing up, particularly once Bill (Albert Brooks), the governor, announces plans to join the Obama cabinet. That means Ella will be in the spotlight, which isn’t the most comfortable position for her. She’s a purehearted, hard-griding policy wonk, not a gladhanding politician who likes small talk. That’s made Bill and her a good team, but now the team is due to break up. What’s more, Ella’s father has shown up for the first time in a decade. But just when that plot seems like it’s ready to start cooking, the movie sidetracks to deal with Ella’s brother Casey (Spike Fearn), who’s lived as a shut-in since splitting with his sort-of girlfriend Susan (Ayo Edibiri) the year before.

Every scene spent with Casey—a cliched character Fearn plays with a Crispin Glover-like intensity—feels like a huge distraction from what ought to be the focus of the film. (Fearn’s mumbly weirdo energy doesn’t help, but then the usually reliable Lowden also goes way over the top, so the fault might lie elsewhere.) But after a while, it becomes clear the film has no focus. Mackey’s charming as Ella, particularly when playing opposite Brooks, but the character ultimately plays like the embodiment of a political idealism meant for a time that’s long since passed (in the scenes when the film decides that this is what it wants to be about). Ella McCay has some fine moments but getting to those little gold nuggets requires a lot of tedious sifting through the sand. —Keith Phipps

Ella McCay is in theaters today.

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Dir. Mike P. Nelson

97 min.

The new Silent Night, Deadly Night arrives with a healthy lack of respect for the ho-ho-horrible 1984 original, a Z-grade slasher movie about a little boy whose traumatic Christmas turns him into a Santa-themed serial murderer. Critics at the time, led by Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, were rightly exhausted by artless Halloween knock-offs, and a notorious television spot for the film set off such a backlash with parents that it was yanked from theaters after six days, despite outgrossing A Nightmare on Elm Street on opening weekend. (Rest assured, the Wes Craven film would have survived the competition long term.) The film’s basic conceit was enough to sustain a straight-to-video empire and a reviled 2012 remake with Donal Logue and Malcolm McDowell. But it’s an artless and risible affair, notable mainly for a sequence where nude B-movie queen Linnea Quigley gets impaled on the antlers of a taxidermied buck.

Where the ’84 version spends nearly half its running time accounting for the many traumas that lead a fresh-faced boy named Billy to grow into an axe murder in a Santa suit, writer-director Mike P. Nelson’s reasonably clever remake gets it done with maximum efficiency. Weird encounter with demented grandpa? Check. Parents slaughtered by a creep in a Santa costume? Check. But Nelson holds the big twist in his back pocket as he moves quickly from Billy as a boy to Billy as a drifter, played by Rohan Campbell, who kills on a seasonal schedule. Constantly in dialogue with an inner voice that calls himself “Charlie,” Billy keeps a grisly advent calendar that he marks up with blood from each day’s kill, picking each new victim in consultation with his imaginary friend.

On the run from his latest bloodbath, Billy hides out in a small town and gets a job stocking shelves at a holiday gift boutique, where he develops a nice rapport with Pam (Ruby Modine), a pretty clerk whose father owns the store. The area has been plagued by a rash of child disappearances, but with Billy in town, the murder rate spikes, too, which somehow doesn’t lead local authorities to ask questions about the mysterious drifter with a shiner in his eye. But such details matter little when Nelson starts turning out some lively exploitation setpieces, like one where Billy sets off a melee at a Christmas party hosted by white supremacists. This Silent Night, Deadly Night wisely replaces the sex-negative conservatism of the original film, where horny teenagers filled up the “naughty” list, with a more jaundiced take on small-town moral hypocrisy. Though he still doles out kills in a thin broth, Nelson puts enough craft and spin on the material to make it better than it has any right to be. Making the best Silent Night, Deadly Night is the very definition of a modest achievement. — Scott Tobias

Silent Night, Deadly Night is clogging up a chimney near you.

Discussion