In Review: ‘Nouvelle Vague,’ ‘Dracula’

Two movies about movies this week as Richard Linklater follows a young Jean-Luc Godard and Radu Jude gives Bram Stoker the AI treatment.

Nouvelle Vague

Dir. Richard Linklater

108 min.

From 1960 until his death in 2022 at the age of 91, Jean-Luc Godard directed or co-directed around fifty films. As Novelle Vague opens in 1959, Godard (Guillaume Marbeck), a film critic for the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma, isn’t sure he’ll even get a chance to make one. Godard doesn’t just live and breathe movies, he views life through the filter of the innumerable films he’s seen. That doesn’t make him a safe bet for producers, however. Godard has a lot of curious ideas about what the future of movies ought to look like that he perfers to express in the form of gnomic aphorisms. (“Cinema is truth 24 frames-per-second,” etc.) It’s a vision that will take elements he loves from the directors he reveres and rework them in his own image while ignoring all the respectable conventions —assuming he ever gets a chance to put theory into practice.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

Yet, as unlikely as that might seem, when the fifties draw to a close, it feels as if his moment might be at hand. After all, Godard’s friend and sometime collaborator François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard) got to make his convention-flouting movie, an autobiographical film called The 400 Blows. Cahiers is staffed with aspiring filmmakers. And besides, movies have gotten so boring. Someone has to save them.

That’s the state of the Paris filmmaking world as Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague opens. By the movie’s end, that world has changed, thanks in no small part to Godard. Written by Holly Gent and Vincento Palmo (whose work was then translated into French by Michèle Halberstadt and Lætitia Masson), the film depicts the making of Godard’s Breathless, a landscape-reshaping crime movie about the doomed affair between a criminal named Michel, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, and an American student named Patricia, played by Jean Seberg. You can only point to a handful of films that changed movies forever. Linklater wants to tell the story of how that movie came to be, from the environment from which it emerged to the last shot.

That Nouvelle Vague looks like it could have been made alongside Breathless is its most immediately striking feature. From the aspect ratio to the film stock, it’s virtually indistinguishable from a contemporary production. The tone, however, is wry, knowing, and resolutely comic, even occasionally sentimental. This is a story with a happy ending, after all, and Linklater plays the setbacks encountered on the way to the film’s premiere as minor mishaps and any clashes as amusing foibles. Godard’s a sour weirdo genius. Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) has none of the real Belmondo’s rough edges. The film offers only the faintest hints of the tragedy awaiting Seberg (Zoey Deutch, winning as always). It’s a light comedy about a bunch of misfits (band of outsiders, maybe?) who come together to put on a show. Godard would probably have hated it.

That doesn’t matter. Linklater’s style has never borne much resemblance to Godard’s but, like many filmmakers, he’s spent a career exploring some of the possibilities by Godard’s willingness to throw the rulebook out the window. As an act of film history, Nouvelle Vague’s at its best in scenes recreating the run-and-gun style Godard favored at the time and in moments when Seberg, fresh off a torturous experience working with Otto Preminger, pushes back at Godard’s direction. It’s superficial by design. Godard remains an obsessive sunglasses-clad enigma to the end. Everyone from Agnes Varda to Roberto Rossellini to Jean-Pierre Melville make appearances, sometimes just for a moment (new arrivals get introduced with a formally composed shot and a title card), sometimes to steer Godard in one direction or another. Linklater’s not particularly interested in exploring anyone’s inner lives in any detail, but his ability to reshape the story into a lighthearted hangout movie, in which characters put aside their differences to get a job done, makes it brisk and entertaining. If anything, it owes more to Howard Hawks than Godard. Maybe Godard wouldn’t have hated it after all. —Keith Phipps

Nouvelle Vague begins playing in select theaters tonight. It debuts on Netflix on November 14th.

Dracula

Dir. Radu Jude

170 min.

The phrase “still wet from the lab” doesn’t really apply to films in post-celluloid world, but for the essayistic social comedies of Radu Jude, the Romanian button-pusher behind Bad Luck Banging (or Loony Porn) and Don’t Expect Too Much From the End of the World, it seems like there’s little time from thought to camera to screen. Maybe historical perspective is best achieved through distance, but there’s something to be said for Jude seizing on the immediacy of digital production and commenting on the world as if issuing devastating quote-tweets in your social media feed. If you’re tired of getting inundated with AI slop on Facebook or, say, the actual verified feeds of government officials, then it’s quite exhilarating to discover that Jude is online, too, reacting with the same revulsion. Though his new film Dracula bounces around to other topics, too, it’s foremost a nasty parody of a world that’s already surrendered to the glossy grotesquerie of AI as a creative tool. Jude is putting himself on the front lines.

Yet the trouble with Dracula is that Jude’s fight-fire-with-fire approach involves flooding the zone with AI, which at 170 minutes can make the film feel like an endless doom-scrolling session. It’s fitfully inspired in stretches, as Jude runs various creative scenarios through a mirthless AI generator, but as a viewer, being inundated with crap still hurts, even when there’s a satirical purpose. There’s also a limit to the quick-and-easy digital aesthetic that Jude is pushing here, which makes the film seem genuinely amateurish and tossed-together rather than a commentary on amateurish, tossed-together art. It too often becomes the thing it’s satirizing.

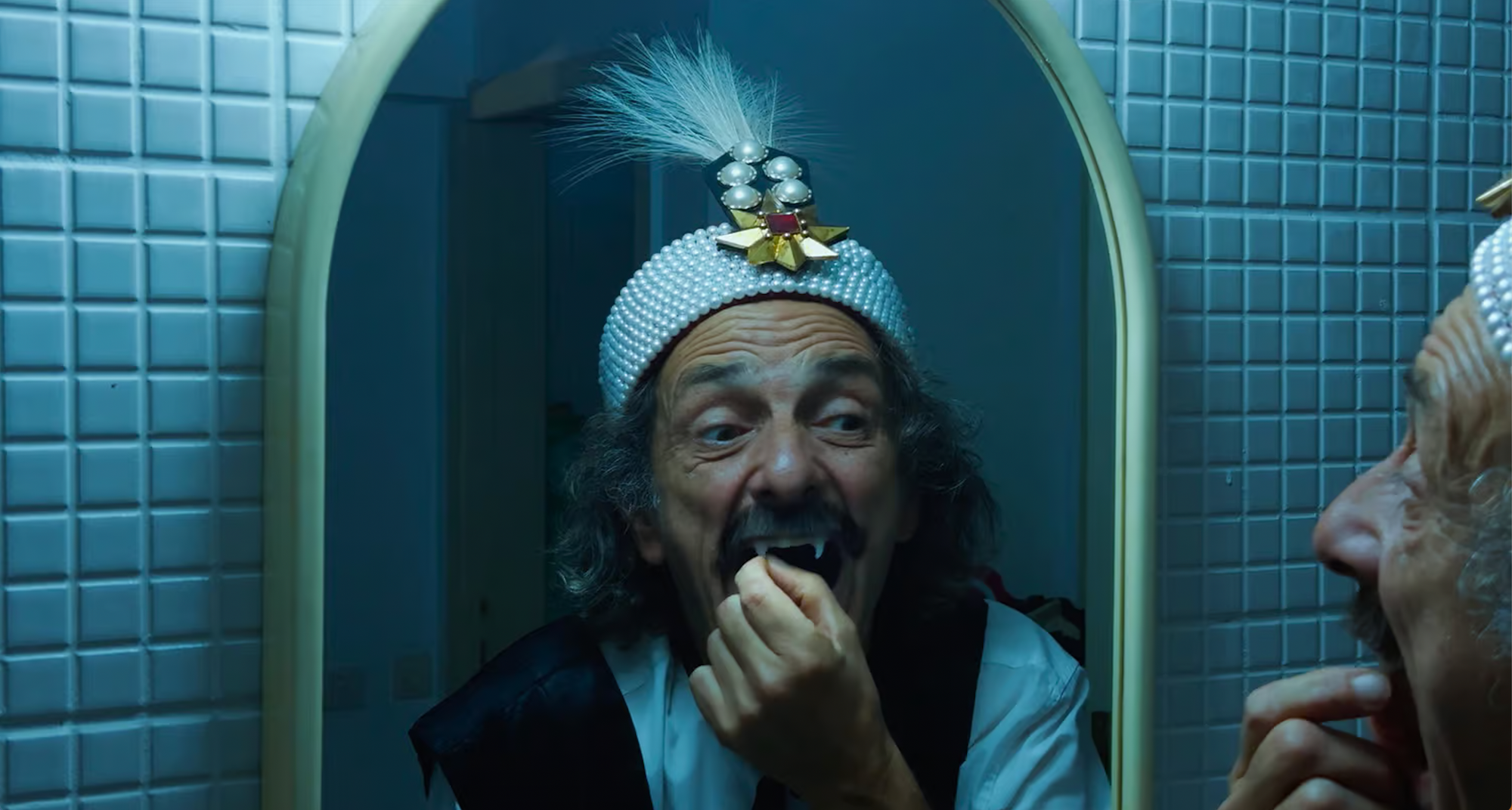

For Jude even to call this movie Dracula is a great bit in itself, given how “loose,” let’s say, its relationship is to Bram Stoker’s novel, despite the Romanian setting that he exploits whenever he gets the opportunity. After an uproariously stupid opening montage where various AI counts declare, “I am Vlad the Impaler Dracula, you can all suck my cock,” the film alternates between two different plotlines with Adonis Tanta starring as the master of ceremonies in both. In one, Tanta plays a creatively stunted film director who offers 14 different prompts to the talking AI generator on his iPad, which then turns these scenarios into mini-movies like an ad-strewn version of Murnau’s Nosferatu or something called “Dracula TikTok.” In the other, Tanta operates a deranged dinner theater where patrons are offered the chance to chase down an aging community-theater vampire (Gabriel Spahiu) and a sexy Mina (Oana Maria Zaharia) on the streets with large wooden stakes. At a certain point, the actors decide to flee into the night for real.

As with Jude’s previous essay films, Dracula is dense with cultural references and political asides, including swipes at Elon Musk and Donald Trump, and footnotes like an expensive Dracula theme park in Romania that turned out to be a $30 million government scam. The AI-mimicking shorts are a hodgepodge of deliberately half-realized ideas—though one eats up 50 minutes—but the wilder ideas hit the hardest, like a “capitalist vampire” sketch in which the count and an AI-projecting robot try to bring a fascist order to the programming floor of a videogame company. Yet the theater subplot doesn’t go anywhere that interesting and there’s a conceptual sameness to Dracula that proves enervating, because Jude can’t pivot away from it easily. His best films have a sense of surprise, grounded in real life yet more malleable as a vessel for satire on one end and a true melancholy about the state of things on the other. Dracula keeps the target too narrow. — Scott Tobias

Dracula opened yesterday in select cities, including New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Discussion