In Review: 'The Conjuring: Last Rites,' 'Riefenstahl'

The Conjuring franchise comes sputtering to a close (for now) while a new documentary treats Leni Riefenstahl's image rehab with skepticism.

The Conjuring: Last Rites

Dir. Michael Chaves

135 min.

For the sake of quality schlock, it’s been more or less fine to overlook the discrepancies between the Ed and Lorraine Warren of The Conjuring franchise—an earnest, pious, godly pair of ghostbusters, played winningly by Patrick Wilson and Vera Farmiga—and the real-life Warrens, who wither a bit under scrutiny. You might understand the Warrens as charlatans, for example, based on the dubious “evidence” that they collected to support their exploits as demonologists, which led to many lucrative books, lectures, and several major motion pictures. Or perhaps you will recoil from the testimony of Judith Penney, who claimed to live under the Warrens’ roof as Ed’s lover for decades, starting from when she was 15 and he was 27. Whatever the case, The Conjuring movies (and their many spinoffs) haven’t been worth much off-screen scrutiny, because these fictional Warrens have been folded into stories that viewers know (or should know) are hokum.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

And yet, The Conjuring: Last Rites, pushes it too far. It’s finally time to rip up the tacit agreement between the filmmakers and the audience that the real-life Warrens are not worth discussing. Because Last Rites, in an effort to wrap up the series in grand and emotionally resonant fashion, have so shamelessly sentimentalized the on-screen Warrens that the stench rises up from the floorboards with a demonic pungency. The precedent here is the Fast and Furious franchise, which started as a gearhead series for the CGI era and has now morphed into an epic story about “family,” which you can glean by the persistent evocation of the word since Paul Walker died. The common denominator for both The Conjuring and the Fast and Furious movies is James Wan, the enjoyably kinetic director who got The Conjuring off to a fine start with the first and second entries and cranked up Furious 7 with an “airdrop” sequence in the Caucasus Mountains. The assumption here is that if mainstream audiences are exposed to these characters for long enough, they’ll develop feelings for them, despite cheap thrills remaining high on the agenda.

Yet The Conjuring: Last Rites, as its 135-minute runtime suggests, aspires to be about more than another by-the-Bible-book affair about the Warrens clearing another home of invasive spooks. The film opens in 1964, when a pregnant Lorraine, in the middle of an investigation turned freaky, gives birth to their daughter Judy, who barely survives the delivery. 22 years later, Judy (Mia Tomlinson) has grown into a clairvoyant like her mother while her parents have drifted towards retirement, partly due to Ed’s heart troubles and partly to skepticism in a post-Ghostbusters world. When they initially hear about the Smurls, a working-class family of eight that believes its Pennsylvania home is haunted, the Warrens leave the problem to others in the Catholic Church to solve. But a tragic turn leads all three of them, plus Judy’s new fiancé Tony (Ben Hardy), to help the Smurls and confront a demon that’s eerily familiar to them.

Returning to the director’s chair after the lackluster third entry in the series, The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It, Michael Chaves has a solid grip on the house style, having also shepherded spinoffs like The Curse of La Llorona and The Nun II. Yet Chaves doesn’t have the witty, frenetic pop of Wan at his best, most recently on display in the zany Argento-by-way-of-Ozsploitation picture Malignant. The Smurls face the more garden-variety shocks of a possessed babydoll, crack’d mirrors, spooky levitations, and various monsters below the bed, under the covers, or in the body. The verse-chorus-verse of a fake scare/pregnant moment of silence/real scare is occasionally effective but mostly numbing, a tired recitation of formula.

Yet the sins of Last Rites would be more forgivable were it not so intent on bending the Smurls’ story in the Warrens’ direction as a tidy button to this iteration of the series. Wilson and Farmiga have acquitted themselves well over the years as Ed and Lorraine, but the film seems to think it’s The Return of the King, inventing loose ends to tie up and stretching out for an extra-long denouement. And to paraphrase another Exorcist knock-off, The Omen: It’s all for you, Ed and Lorraine. It’s all for you. — Scott Tobias

The Conjuring: Last Rites opens in theaters everywhere tonight.

Riefenstahl

Dir. Andres Veiel

115 min.

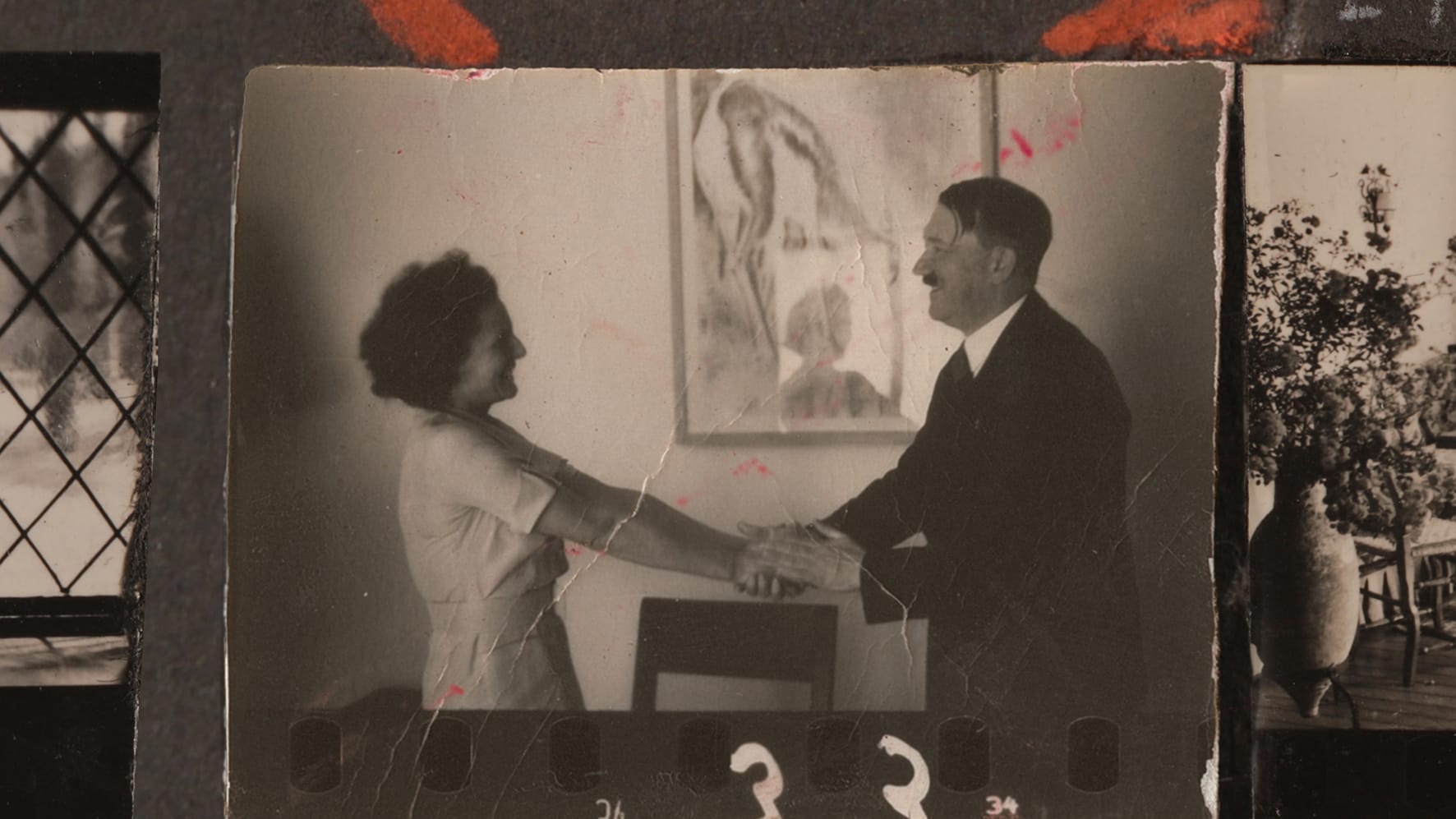

One of the most damning images in Riefenstahl passes without much comment. It’s a photo of Leni Riefenstahl greeting Adolf Hitler in which both wear expressions of genuine warmth. Best known for her documentaries Olympia and Triumph of the Will—each in their own way visually stunning tributes to Hitler’s fascist vision of Germany’s future—Riefenstahl spent the decades after World War II denying any personal connection to Hitler, Goebbels, or other high-ranking members of the Third Reich. She was never a true believer, she claimed until her death in 2003 at the age of 101, but merely a freelancer realizing projects conceived by others. Yet there it is: the truly grotesque image of Hitler in an unguarded moment expressing affection for a friend. And there’s Riefenstahl, mirroring it.

Never particularly convincing, Riefenstahl’s defense takes a series of crushing blows dealt by Andres Veiel’s documentary. Produced by German journalist Sandra Maischberger, who gained access to Riefenstahl’s extensive archives, the film fleshes out her story and fills in some gaps Riefenstahl was happy to leave vacant. Diaries reveal a chumminess with Hitler’s inner circle during his reign. Taped phone conversations find her yucking it up with Albert Speer after his release from prison in the early ‘60s. Evidence supports stories of her using Roma concentration camp prisoners as extras in the movie she made after discovering she had no stomach for documenting the war from the front line.

Yet some of the most telling moments come from Riefenstahl herself, like unused footage from the thorough, but sanitized, 1993 documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl in which she argues with director Ray Müller about what should and should not be in the movie and a ‘70s TV appearance in which she turns combative as the mask slips and she stops just short of taking up her old positions. The many admiring letters and answering machine messages she received from those tired of being ashamed of Germany’s past suggest that that dog whistle sounded loud and clear.

Veiel's film assumes viewers arrive with some knowledge of Riefenstahl’s past and at times feels designed to short circuit any arguments for her on aesthetic grounds. The powerful and influential images she created speak for themselves, sure, but they’re built upon a foundation of horrors. Veiel also expects his audience to draw their own conclusions without having to push the too hard, letting an Allied intelligence report suggesting Riefenstahl and Hitler were lovers appear on screen without comment and offering no commentary on Horst Kettner, Riefenstahl’s much younger late-life lover/assistant beyond his constant, unsettling presence. Late in the film, in unused footage from another documentary, a nonagenarian Riefenstahl instructs the director how best to light her to obscure her wrinkles. She was always the artist,always trying to cover up the impossible-to-conceal. —Keith Phipps

Riefenstahl opens at Lincoln Center in New York tomorrow. Future dates can be found here.

Discussion