In Review: ‘Train Dreams,’ ‘Predator: Badlands,’ ‘Peter Hujar's Day’

Three films today about the small yet majestic destinies of an early 20th century logger, a freelance photographer, and an extraterrestrial runt.

Train Dreams

Dir. Clint Bentley

102 min.

It’s easy for someone to get lost in the America of Train Dreams, but getting lost isn’t the same as disappearing. Early in the film, an adaptation of Denis Johnson’s beloved novella of the same name, director Clint Bentley lingers on a shot of a pair of work boots that have somehow become embedded in the trunk of a tree. On first sight, this looks like an inexplicable phenomenon, an image out of what Greil Marcus dubbed the “old, weird America” that echoed with folk songs of far-flung origins in forms that had mutated to reflect their new home. Yet before Train Dreams ends, we learn how those boots came to be hung there and who wore them, a name undoubtedly fated to be lost to history but someone who left his mark on the land nonetheless.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

Set in the Pacific Northwest, Train Dreams takes place, initially at least, in the early years of the 20th century, where Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton) lives a semi-itinerant existence, spending the warm months helping clear the forest and building new railway lines and the cooler seasons hunkered down by a lake near a small town. People know him, but not well. But then Robert doesn’t really know himself. An orphan of unknown origin, he’s fended for himself his whole life. He’s done so quietly, but not without introspection. Early in the film, Robert witnesses the murder of a Chinese rail worker accused of theft, an incident he doesn’t stop and maybe even enables. It happens so fast it’s not entirely clear—to us or to Robert—what happens or what Robert could have done differently. But we do know the moment haunts him the rest of his life.

Co-writing with frequent collaborator Greg Kweder (Sing Sing), Bentley transforms Johnson’s story into a Terrence Malick-inspired reverie of images and overlapping emotions, accompanied by large chunks of Johnson’s prose via Will Patton’s narration. Patton’s delivery—at once tender and matter-of-fact—complements Edgerton’s masterfully understated performance. He plays Robert as a man who feels more than he can express yet Edgerton makes his attempts to understand both the joy and sadness of his experiences legible and dramatically compelling even when Robert doesn’t attempt to put them into words. Talking doesn’t come naturally to Robert, but companionship does. He forms bonds, however temporary, with the other men on his crew (most memorably one played by William H. Macy, in a colorful and haunting turn). He marries Gladys (Felicity Jones), an understanding woman with whom he starts a family. Others he meets, including a forestry worker played by Kerry Condon (arriving late in the film for an unforgettable scene), easily take a liking to him. Yet Robert always seems to be experiencing life at a slight remove, forever attempting to bridge a gap of understanding separating him from the world around him.

Though told largely in chronological order, Train Dreams conveys Robert’s experience less by a story with a beginning, middle, and end than a collection of moments from his life, puzzle pieces Bentley renders with great beauty and occasional moments of horror. Like Robert, they belong to the past, but a past that remains with us. The coming of the modern era plays out over the course of Train Dreams, usually deep in the background. As the film progresses, Robert starts to resemble a vestige of another age, and another way of living. It’s one quickly giving way to the world Robert, however unwittingly, helped create, one that will have no place for him or others of his kind. But look around and you’ll see traces of him everywhere. —Keith Phipps

Train Dreams opens in theaters (where it should be seen this weekend) before premiering on Netflix on November 21st (where it will still look good, but see it screened if you can).

Predator: Badlands

Dir. Dan Trachtenberg

107 min.

One score and 18 years ago, the original Predator arrived as a vehicle for then-ascendent action star Arnold Schwarzenegger, casting him as the leader of a paramilitary rescue unit in Central America that encounters an extraterrestrial hunter with the strength, stealth and technological wizardry to wipe out his entire team. This single threat made it essentially like Alien on dry land, which may explain how, several sequels and crossovers later, the two universes have intertwined across multiple media. But like any franchise, the Predator movies have not only taken on mythological weight over time, they’ve had to adapt, in their fittingly chameleonic fashion, to changes in the culture. And so now we have Predator: Badlands, in which a member of this fearsome clan is likable but a bit of a runt, as yet unfit to slaughter up to alien standards. Call this How to Train Your Yautja.

As the first PG-13 rated movie in the franchise, Predator: Badlands feels geared toward the younger generation in a way that’s likely to bristle diehard fans, who may object to an entry that occasionally invites an adjective like “adorable.” But director Dan Trachtenberg, who made the widely admired Hulu prequel Prey as well as the excellent 10 Cloverfield Lane, is a skilled craftsman who’s willing to sacrifice Hall H dogma at the altar of a more generous entertainment. For all the sentimental calculus behind its themes of surrogate families and toxic masculinity, the film comes by its squareness with genuine ardor and delivers the goods with as much force as its rating allows. It’s about as far away from an ’80s Schwarzenegger project as possible while also feeling tonally like The Goonies by way of Stranger Things. Choose your own nostalgia.

On the arid, brutal planet of Yautja Prime, the determined young Dek (Dimitrius Schuster-Koloamatangi) strives to fit into the brutal culture of his people, but he’s considered so small and weak that even his father would rather he die than shame the family any further. Dek intends to prove his worth by doing the impossible and hunting a kaiju-level monster called a Kalisk that’s killed every Predator that tries to claim its head as a trophy. Not long after arriving on the Kalisk’s home planet, Dek discovers that merely surviving in this hostile place, with its animated tree branches and poisoned thorns and venomous river snakes, is next-to-impossible even before having the opportunity to confront the beast. But he gets some help from Thia (Elle Fanning), a synthetic from the Weyland-Yutani corporation who’s also been sent to capture the Kalisk and who knows more about how to survive on the planet—if not that much more, because the bottom half of her body has been torn off.

The Dek-Thia relationship is basically a Wizard of Oz scenario, with Dek traipsing down a cursed path and Thia acting as the Scarecrow, an amiable being who’d be stuck in place forever if he hadn’t come along. Only Dek is a bit crankier than Dorothy, since Yautjas are bred to be lone, ruthless warriors, and so the burden is on Thia to bring a little sunshine into his life. Weyland-Yutani synthetics have turned their reputations around since Alien, but Fanning’s cheery performance as Thia takes some getting used to, for the audience as much as Dek, who’s inclined to dismiss his companion as a “tool.” Having the shared goal of besting the Kalisk and getting off this godforsaken planet helps forge a little trust, and Trachtenberg keeps the action setpieces coming at a steady clip. Predator: Badlands may be formulaic and a little cutesy, but its relentless crowd-pleasing instincts wear down your defenses. You feel like the Dek to its Thia. — Scott Tobias

Predator: Badlands drops into theaters tonight.

Peter Hujar’s Day

Dir. Ira Sachs

76 min.

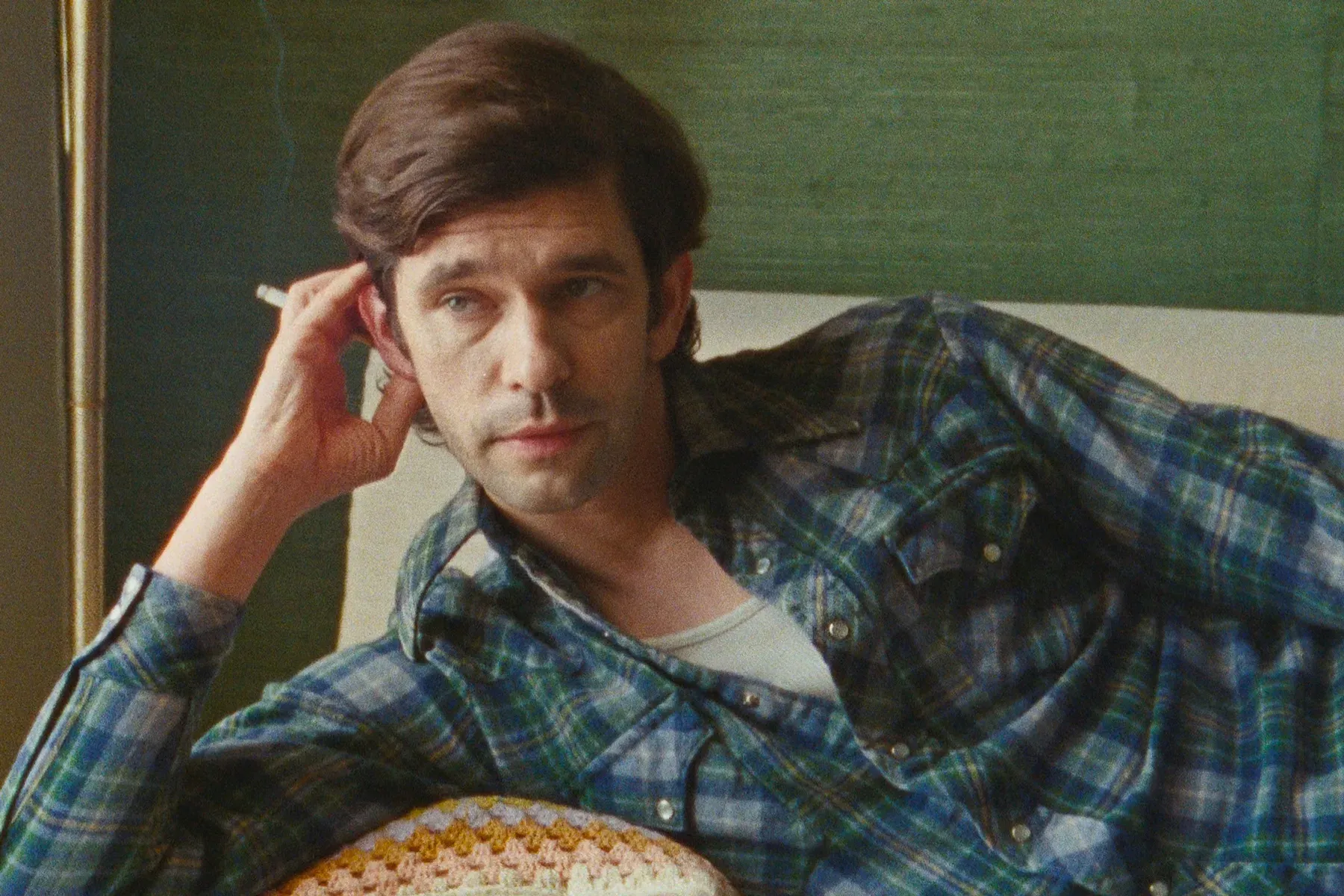

Peter Hujar’s Day opens with some explanatory opening text that doubles as an act of expectations-setting. It’s a slice of life, but one cut so thin it practically required professional deli equipment to create. Writer Linda Rosenkrantz, a fixture in the downtown art scene of the 1960s and ’70s, set out to create a book based on recordings of her friends and acquaintances discussing what they did in a single day. Rosenkrantz never completed the project, but a transcript of her conversation with photographer Peter Hujar recorded in December 1974 survived. Roskenkrantz adapted the material into a book in 2021, 34 years after Hujar’s AIDS-related death. That in turn served as the inspiration for this new Ira Sachs film, which reworks the material as a quiet, illuminating two-person drama starring Ben Whishaw as Hujar and Rebecca Hall as Rosenkrantz.

Now recognized as a major figure in 20th century photography, Hujar had friends and acquaintances that included everyone from Andy Warhol to John Waters to Fran Leibowitz. But if Sachs was ever tempted to expand the scope of the film beyond the single day documented by Rosenkrantz, there’s no sign of it in the patient, studied film. Set entirely within Hujar’s Manhattan split-level studio apartment (with the occasional trip to the building’s roof), Peter Hujar’s Day depicts Hujar recalling the events of the previous day while Roskenkrantz looks on affectionately, occasionally asking for a bit more information or expressing concern that her friend isn’t eating enough and smoking too much, but mostly letting him talk.

For Hujar, the day in question wasn’t that remarkable, one that began with a visit from an Elle editor picking up some photos and a call from Susan Sontag and ended with some darkroom work. Even an afternoon spent photographing Allen Ginsberg for the New York Times gets treated as a disappointment. Hujar feels like the two never made a connection and that their lack of chemistry can be seen in the results. He couldn’t know that one of the photos, an image taken on the streets of the Lower East Side, would become one of the most famous images of Ginsberg. Such concerns fall outside the scope of the film anyway.

Rosenkrantz’s gentle prompting helps make Hujar’s account more than a mere catalog of his daily grind. His atrocious eating habits, stubborn perfectionism, off-hand recollection of hooking up with a man who used “buddy” as a post-coital term of endearment, and concern about getting paid by his freelance clients reduce the sweep of a cradle-to-grave biopic down to a pocket-sized portrait of the artist as a young man. The singular word “portrait” isn’t quite right, however. Both Whishaw and Hall deliver lovely, tender performances that capture the friendship between the writer and her subject. Hujar does most of the talking, but without Rosenkrantz looking on, prodding where needed, and creating an atmosphere of warmth and support, he wouldn’t have talked at all. This day and its trapped-in-amber depiction of a tiny corner of ’70s New York, would have been lost to time like any other day no one thought too much about while living it. —Keith Phipps

Peter Hujar's Day opens in limited release this weekend before expanding.

This is another big week for new releases so we'll be back tomorrow with another batch of reviews. Check back in for our takes on Die My Love, Christy, and Sentimental Value.

Discussion