In Review: ‘Wicked: For Good,’ ‘Zodiac Killer Project’

The second part of "Wicked" exposes the flaws of a front-loaded musical and a true-crime doc deconstructs the true-crime doc.

Wicked: For Good

Dir. Jon M. Chu

137 min.

Though it was always going to be great for the bottom line, the decision to cleave the Broadway hit Wicked into two parts for the screen was likely to thin out a book that was already slight and expose the fact that the musical is conspicuously front-loaded. The two most memorable songs, the fizzy Glinda (Arianda Grande) number “Popular” and the soaring Elphaba anthem “Defying Gravity,” are in the past now, as is the lively odd-couple banter between the two women at Shiz University in Oz, where one soaks luxuriantly in the adoration of her peers while the other is a green-skinned outcast. That leaves a handful of replacement-level showstoppers, two time-killing new numbers (“No Place Like Home” and “The Girl in the Bubble”), and the strenuous labor, carried over from the Broadway show, of aligning the fractured mythology of Wicked with the canonical events of The Wizard of Oz. For a project that already seemed too machine-tooled and impersonal, you can practically hear all the gears clicking neatly into place.

Part One ended on a strong transitional note, as Elphaba, disillusioned by the secrets and lies of the Wizard (Jeff Goldblum) and her once-encouraging mentor Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh), embraces her fate as the Wicked Witch of the West and takes off with the Grimmerie spell book. Her friend Glinda declined to go along, which again puts them at odds, since she’s now Glinda the Good and has a positive ceremonial role to play in Oz. As the timeline nears the point where a certain naif from Kansas crash-lands into Munchkinland, fans of The Wizard of Oz will want to know answers to key questions like, “Wait, how does the Tin Man become the Tin Man? And how does the Scarecrow become the Scarecrow? And hey, why does Glinda send Dorothy all the way to the Emerald City when she knows the Wizard has no actual power? And how in the world is a bucket of water all it takes to kill the Wicked Witch?”

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. It would be "wicked" smart to become a paid subscriber and join our community.

Not to worry! All those questions are answered and a few of them wittily. One of the enjoyable carry-overs from the Broadway show is how Dorothy is of such minimal importance in the grand scheme of things that Glinda seems put out by having to send her on her way. The past and future of Oz is of much greater consequence, as is Glinda’s friendship with Elphaba, which is riven by tensions, like their mutual romantic interest in the ultra-bland prince Fiyero (Jonathan Bailey) and their roles in the kingdom’s new political order. The entire conceit of Wicked is that Elphaba is misunderstood and this second part works hard to reinforce the theme through a series of well-intentioned mistakes that confined her to a role that she neither wants nor deserves. (Cue “No Good Deed.”) The sturdiness of Elphaba and Glinda’s bond throughout these tragic miscues—and Erivo and Grande’s fine dramatic and vocal performances—give this rickety enterprise a solid foundation.

But whenever the two are separated in Wicked: For Good, which is often under the circumstances, there’s an abundance of characters and events that are not worth the attention. Elphaba’s paraplegic sister Nessarose (Marissa Bode), useful mostly as a device to get Elphaba to Shiv in the first part, isn’t given enough time to make her heel turn play, which hangs her sour Munchkin companion Boq (Ethan Slater) out to dry. Fiyero, too, is an exceedingly bland side character, saddled with a love duet with Elphaba (“As Long As You’re Mine”) that’s so cheesy, it’s a surprise to remember it’s part of the original show. It seems apt that Boq and Fiyero’s stories intersect with The Wizard of Oz because they don’t stand well enough on their own here. But after two movies and 300 minutes, the overall impact of Wicked is fatally slight for such a massive investment, a minor “What if?” scenario stretched well beyond its limits. — Scott Tobias

Wicked: For Good opens tonight at theaters absolutely everywhere.

Zodiac Killer Project

Dir. Charlie Shackleton

92 min.

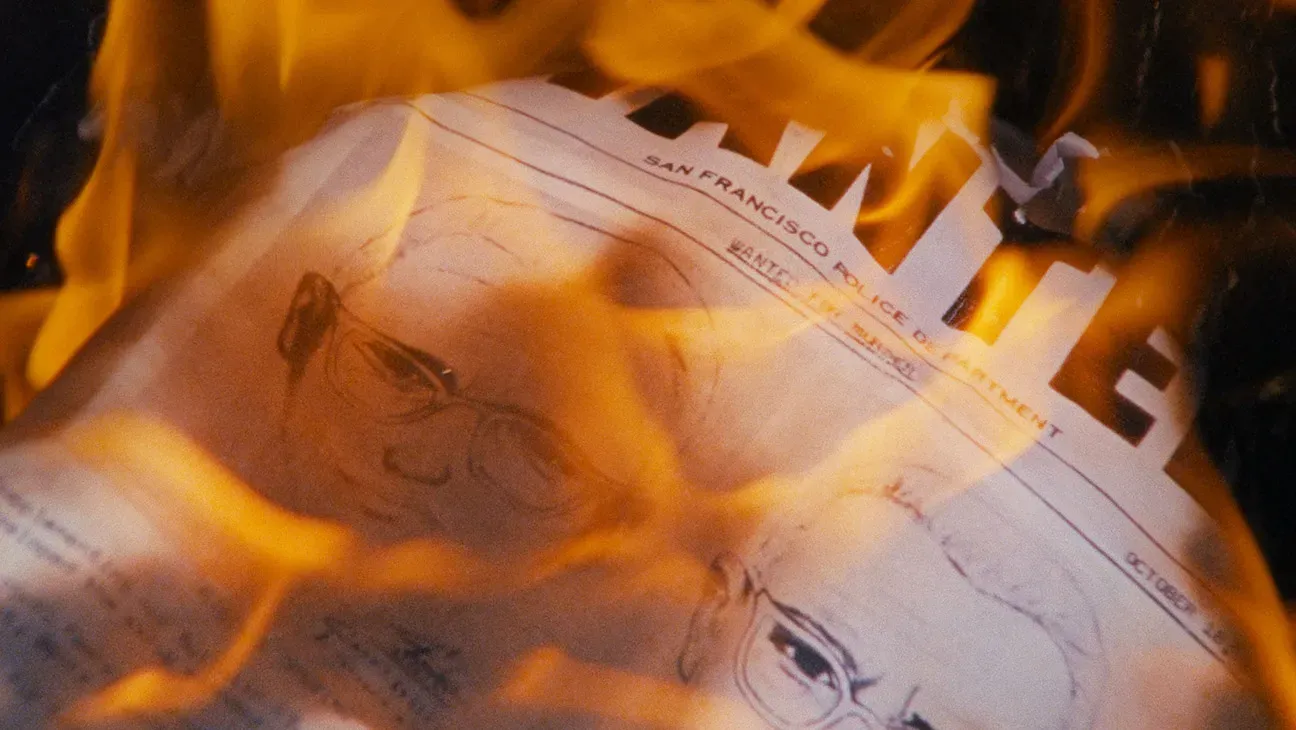

“If we’d made the film, there would have been a car here,” director Charlie Shackleton says in voiceover against the image of an empty California rest stop parking lot. He then goes on to describe what else the scene would have contained had he not lost the rights to make a documentary based on former California Highway Patrol officer Lyndon Lafferty’s 2012 book The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge: vintage cars, reenactments with extreme close-ups, Lafferty’s inner monologue, and dramatic driving footage. “Fuck, it would have been good,” he concludes before the film’s credits begin.

Maybe, but it almost certainly wouldn’t have been as good as the film Shackleton ultimately did make. On the face of it, Zodiac Killer Project is a walkthrough of the film Shackleton would have made had Lafferty’s family not decided to withdraw from the film. Via fair use and secondary sources, the director reconstructs Lafferty’s decades-long (and, frankly, pretty sketchy) attempt to reveal a fellow Solano County resident as the never-captured serial killer. In the process, Shackleton also explains how how he could have squeezed Lafferty’s story into the familiar form of a contemporary true crime doc by focusing on some details while ignoring others, suggestive editing, and drawing from the a bag of stylistic tricks,from an eerie opening credits sequence to a late-film attempt to offer big-picture ruminations. There’s another level to it as well: Even while laying bare the mechanics he would use to tell a story likely to trip viewers’ bullshit meters and calling out one genre cliche after another, Zodiac Killer Project almost works as a compelling true crime doc anyway, up to the way it repackages a crushing anticlimax as a thrilling conclusion.

Shackleton mostly refrains from passing judgement on the true crime world and instead contents himself with pointing out these genre mechanics with puckish amusement until, late in the film, talk turns to the Ryan Murphy produced series Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. (It’s not a documentary but very much within the true crime sphere.) Shackleton goes on about the hypocrisy of ending the series with a tribute to Dahmer’s victims after hours of exploiting their deaths when the voice of an off-screen assistant says, “You watched it, though.” Shackleton’s reply: “Yeah, it was good.” A simple condemnation of true crime documentaries might have been satisfying, but Shackleton understands he’s not in a position to stand outside that world and point fingers. He’s a fan, however reluctantly, and was trying to make his own contribution to it, after all. (Though it’s hard to imagine a director with Shackleton’s sensibility playing it straight. He once made a 10-hour film called Paint Drying as a protest against the practices of the British ratings board.) And besides, maybe true crime has so informed our notion of what’s true and how that truth must be told that there is no standing outside it anymore. —Keith Phipps

Zodiac Killer Project opens tomorrow in limited release.

Discussion