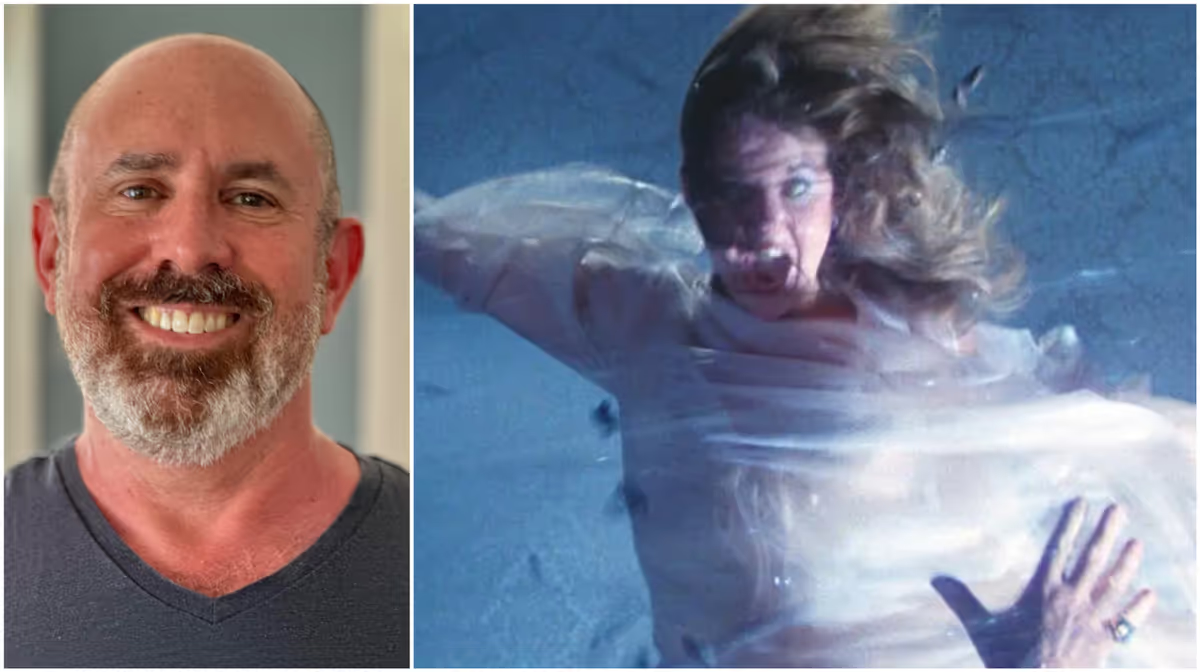

Interview: David Kittredge on the reviled and revived 'Exorcist II: The Heretic'

With his new documentary 'Boorman and the Devil,' David Kittredge goes deep into the tortured history of a misunderstood horror sequel.

Gene Siskel called it “the worst major motion picture I’ve seen in almost eight years on the job.” After viewing a portion of the film in a Technicolor lab before its release, William Friedkin called it “the worst 40 minutes of film I have ever seen, really, and that’s saying a lot.” At the Chicago Critics Film Festival in 2013, Friedkin would go on to talk about a preview screening where the test audience was so enraged, they sparked a riot that had the studio bosses literally fleeing the theater.

But what if Exorcist II: The Heretic wasn’t the worst horror sequel ever? What if it was, in fact, the obviously flawed yet visionary work of a director, John Boorman, who set out to make a subversive sequel that defied the visceral aggression and conservative values of Friedkin’s original box-office smash? Is it time to look at Exorcist II a different way?

David Kittredge, a producer and editor who worked on the four-part Shudder series Queer For Fear: The History of Queer Horror and the director’s cut of 54, certainly thinks so. Years in the making, his terrific new documentary Boorman and the Devil premiered earlier this month at the Venice Film Festival and argues persuasively that Exorcist II deserves the cult following that it has quietly accumulated over the years. (The film makes its North American debut at Beyond Fest in Los Angeles on September 24th and is still seeking a distributor, though Kittredge is optimistic.) Surveying a huge chorus of talking heads that includes not only Boorman, the late Louise Fletcher, and Linda Blair but a host of below-the-line crewmembers, Kittredge tells the complete story of the film’s cursed production and disastrous reception while also assessing its immense artistic ambitions. Whether Exorcist II is a good movie is up for debate—a question that Kittredge poses to his subjects in an inspired montage— but Boorman and the Devil reframes that debate in a way that brings the film closer to the New Hollywood misfires of the era than the cynical sequel people might presume the film to be. A week after the premiere, Kittredge talked to The Reveal about his personal obsession with Exorcist II, the passion of the artists who worked on it, and why Friedkin may have been so famously enraged by it.

What is your relationship to Exorcist II? When did you first encounter it and have your feelings on it evolved over time?

The first time I saw Exorcist II: The Heretic, I was a teenager. I think I was like 14 or 15, and it was at the point where I was just basically raiding the video store for titles. I saw it on Betamax. I rented it after I saw The Exorcist, which floored me. It floored me like few films had, especially the edit, because I come from an editorial background and I really love editing. I think editing is the best part of cinema.But what [William Friedkin] does with the pace of that film and the way that he cuts intense scenes with no score… I had never seen anything like that at the time. So I got The Heretic knowing it had a bad reputation and not having seen any of John Boorman's other work, though I knew he was an important director. I hadn't seen Deliverance yet. That was probably his best-known movie at the time, because this would have been before Hope and Glory. So I watched what was the recut version. This was the version that was in Europe with [Richard Burton] dying at the end and the prologue. It’s all restructured in the first third and it’s 16 minutes shorter. I remember thinking, “Okay, that wasn’t good, but that wasn't bad.”

And when I got to college, that was when Warner Bros. released the original theatrical version on video for the first time, and I saw it, and that really floored me, because it’s a very different film, much more cohesive and coherent. It does suffer from all of the things that Exorcist II suffers from, in spades, but it's very much of its own thing. It’s an eloquent statement, whereas the recut version is kind of like trying to put Band-Aids on what it really is, which is not a horror movie. [The shorter edit] tried to horror movie it up, to varying degrees of success. Over the years, I just became fascinated with this film. For my 30th birthday, I got a video projector and set it up at the house of a friend of mine who had a big wall. I projected it off of VHS for everybody, because people hadn't seen it. And I got a lot of shit for that for a while. Then I read the Barbara Pallenberg book [1977’s The Making of Exorcist II: The Heretic], which I think is one of the best making-of books for any movie, It’s out of print, but I think you can find them on eBay. [Ed. note: You can. The cheapest we could find is $74.99 but it can be found on the Internet Archive.] It’s very warts and all, and it’s amazing to read.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

I think it would have been so easy for John Calley at Warner Bros. to greenlight a movie about another possessed kid, with or without Linda Blair. Yet they chose to do this, and they did it with the biggest budget in Warner Bros. history. They did it with a mad visionary like John Boorman, who in my opinion is one of the greatest filmmakers who has ever stepped behind a camera, and they made this thing that was almost intentionally designed to upend the expectations of the audience, which is very subversive.

I have these posters and lobby cards [for the film] up in my hallway, like the Japanese poster and all this stuff. And my friend, a documentary filmmaker named Jeffrey Schwarz, basically said to me in 2017, “You need to make this documentary.” And I was like, “No, Jeffrey. I don’t want to make a documentary. I know what it takes to make a documentary. It is just painful and awful, and it takes forever and you lose your mind.” Then he said, “If you don’t make this documentary and make it soon, no one will ever do this. The story will never be told. Because these people were getting up there [in age]., Boorman was up there. Louise [Fletcher] was up there. Rosbo [Pallenberg, a key script contributor] was up there. And it annoyed me profoundly, because I knew he was right and I needed to live in a world where this story was told. What it comes down to is I really, really, really wanted to see this movie, and the journey to making it has been something that I will never forget. It’s taken over seven years and so many pitfalls, including the pandemic holding us up. It helped clarify for me what I find important in cinema as an art form.

I feel like there are two ways you can look at the movie. One, “Is it good? Does it do what it sets out to do? Does it tell the story the way that it thinks it does? And does it succeed at that?” And I don’t think Exorcist II: The Heretic succeeds at that. I think that Boorman would even agree and has agreed. But the other way of looking at it, which I find far more important, is: “Is it interesting? Does it try things? Is it trying to subvert what you think is going to happen? Does it try to subvert narrative convention? Is it trying to do something in a way that you’ve never seen before?” And I find Exorcist II: The Heretic to be one of the most fascinating films I think I’ve ever seen.

To me, one of the most compelling aspects of the documentary is how you frame it. We tend to put sequels, particularly sequels to horror movies, in their own vulgar category. But you’re placing Exorcist II among the examples of ’70s auteur visions gone awry, like Heaven’s Gate.

I wanted to recalibrate people’s thinking about what this movie actually is. I think that the worst and most inept critique of this movie was that it was a cash grab. I’ve read that in so many of the reviews at the time and I think Exorcist II: The Heretic was the opposite of a cash grab. They could have done a cash grab. It would have been so easy. They did something very different. With the biggest budget in Warner Bros. history, they set out to make a subversive experimental film and give it one of the widest releases in history. To just say it’s a sequel is lazy thinking. There are a lot of valid critiques of this film and Boorman would absolutely agree with them. But one of the reasons that I [made this documentary] is because the film [has more in common] with a Sorcerer or a New York, New York than it does something like Jaws 2.

It wasn’t a cynical enterprise.

No. We look back at the ’70s. the Hollywood New Wave. We tend to remember, like, the McCabe and Mrs. Millers and the Chinatowns and the Godfathers. Sometimes we remember films like Electra Glide in Blue. Sometimes we remember the smaller kind of misfire, like any of the Altman movies in that period save for maybe Nashville. Like Buffalo Bill or A Wedding or Quintet, for God’s sake. Or think about Peter Bogdanovich’s work past The Last Picture Show, like Daisy Miller or At Long Last Love, which is another famous disaster. These are not cash grabs. Exorcist II is absolutely an example of the ’70s New Hollywood, because there is absolutely no other time that a movie that crazy and that out there could exist, especially as a follow up to such an iconic film, the third-highest grossing movie ever made. To make Exorcist II is one of the most prime examples of ’70s Hollywood thinking that I can think of. Even though The Godfather Part II did something different and interesting, it was basically set in that world. The French Connection II was a fine action follow-up, but it didn’t really try to subvert anything. That was the ethos of the sequels. I can’t think of another sequel that tried to upend the original as much as Exorcist II.

One of the striking elements about this documentary is how deep you go into the production. You’ve got script supervisors. You have a lot of people who were really deep behind the scenes. What was involved in wrangling all this talent?

It’s one of the reasons why this film took so long to make. It wasn’t easy finding everybody. But most of these people are findable. Take Victor Hsu, who was the Second Assistant Director. This was one of his first films. He’s had a huge career in Hollywood since. I forget how I actually did get to him. I think it was like a Linkedin DM or something. Most of these people are just normal craftspeople. But the striking thing was that every single person I talked to, even people that did not want to be in the film, remembered this shoot like it was yesterday. I prompted them a little bit because I knew the schedule. I had the script supervisors’ pages, which had dates on them. But [the production] had a huge impact on them. Many of them were just starting out and this was just a mega production and John made an impact on all of them. They all told me the same thing about John, which was that he was absolutely committed and visionary and perfectionistic. He was really hard on camera, but he was such a sweet, lovely, charming, wonderful guy—like the opposite of what you heard about Friedkin. Almost diametrically opposite,with the exception of them being perfectionists. For such a hated movie, everybody on the crew was deeply committed and John inspired that in people. He was convinced he was making a great film and he convinced everyone else that they were making a great film.

When the film was finished and received that way it was, you can hear in everyone’s voices how personally devastating it was for them. It hurt them. It hurt their hearts. And, you know, say what you will about the entertainment business. Nobody gets into the entertainment business, especially at that time, for any reason except that they love movies. You can make more money elsewhere and you can get much more standardized and reliable work in almost any other field. At the end of the day, you go to work. You do your thing. Sometimes the movie is good, sometimes the movie is bad, but their contribution to this was important to every one of them. It’s that love that I don’t think is talked about enough in documentaries about movies. You can hate the film, but, you know, don’t call the people who made it “cretins” like Rex Reed did.

To that end, the standout line to me in the documentary was Louise Fletcher likening her experience to a great spaghetti dinner, with the good and bad as different strands. It’s such a terrific quote both about the movie and about her life in general. This may have been a nightmarish shoot and the film was poorly received. But the survey you get from cast and crew tells a more complicated story.

It was a very special time in the business. It was a very special bunch of people. It was a very special project. And especially [if you consider] where we’re at right now, in 2025, with the movies that are now coming out—and I'm mostly talking about the big studio releases. The more people I talked to about Exorcist II, the more open they were about their lives and their careers and what this particular movie meant to them. I don’t know what else you can say about any work of art that’s more profound. Louise's spaghetti dinner line at the end, which is basically her send off, I couldn’t edit that without crying for a really long time. She passed away a few years ago. And I’m very, very grateful that we got her booked before she passed. The way that she talks about her life and her art… that’s an artist's life. It is about good and bad. It is about making Deliverance and then The Heretic. You can’t make Deliverance without taking chances and you can’t make The Heretic without taking chances. And if you’re not taking chances, you’re not an artist. And that’s kind of the point.

That’s part of Boorman’s magic, too. My God, all the chances that he took with Excalibur. Geez, that could have gone south in about 30,000 different ways. And I actually think it’s his best film. [Kittredge contributed a commentary track to the Arrow 4K edition of the film.– Ed.] It just comes back to [the question], do you view movies as purely an escape mechanism to get out of your life or do you think that they’re actually works of art? I think if it’s the latter, it’s just far more, far more important that a movie try things and be interesting and have depth than just be enjoyable.

You expect filmmakers to have a certain amount of solidarity with other filmmakers, but The Exorcist II strikes me as the rare example of hostility towards the very idea of the film existing. William Friedkin was especially hostile, but also [William Peter] Blatty. And Ellen Burstyn wanted nothing to do with a sequel.

“Hurricane Billy.” First off, Ellen Burstyn had said no before John Boorman came on board. So I don’t think John Boorman, plus or minus, would have changed her mind. I don’t think she was coming back no matter who was directing it. She simply didn’t want to do that again. As far as Blatty and Friedkin, mostly Friedkin, they felt like The Heretic set out to undermine The Exorcist. And I don’t know if they’re totally wrong about that. Boorman had disdain for The Exorcist. He thought it was well made, but he thought it was basically a negative movie with shock value, almost kind of designed to make you enjoy the abuse of a child. He famously refused to direct it, and he tried to talk [John] Calley out of making it at all. Luckily, Calley ignored him and got Friedkin and it made a gazillion dollars and is now a masterpiece. I never met Friedkin, but I’ve seen a lot of his interviews. He had a lot of opinions and disdain for a lot of things. The fact that someone made a sequel to his greatest success and went in this totally crazy different direction… Boorman did not make a horror movie. The first scene undermined Friedkin’s film. The first scene is Richard Burton unsuccessfully exorcising a woman. Friedkin’s movie was basically a conservative treatise about how secularism is never the answer and when the shit hits the fan, you’re gonna turn to the old priest, conservative biblical rights, and all that stuff. It is, in effect, an extraordinarily conservative film as many horror films actually are. The Heretic is an extremely progressive, extremely feminist film. And I think that was also one of the reasons it was so completely rejected in ’77.

I re-watched The Exorcist II before this interview. And one aspect that stood out for me as a plus is something you address in the documentary. You show that the producers originally had all of these locations in mind for where this movie was going to be shot, but none of them worked out. So the film was mostly done on a soundstage. And watching the film, it seems like that was the best possible thing that could have happened to this movie. The unreal quality of the spaces and sets in the film is a standout quality. You even compare it here to Black Narcissus.

Black Narcissus was a direct inspiration for Boorman. He said over and over at the time that he was tired of naturalism. The film he did right before this was Zardoz, which is really not naturalistic, but Deliverance kind of is. It has some dreamy moments, but it’s mostly grounded in location and very visceral. You’re right there. You’re in the woods, you’re on the river. I think Boorman wanted to do something very dreamy and theatrical and eerie with Exorcist II, and they shot it all on soundstages. He’s like, “We’re going to make Africa with hillsides and landscapes and exteriors. We're going to build huts. We’re going to blow sand everywhere.” It was very important that he had control over the visuals. That was another reason they did it on the soundstages, so he could have absolute control over the look and feel of the film. Because the look of this film was really paramount to him, and it is one of the most unique-looking movies I’ve ever seen. They omit blues and greens and purples and it’s all reds and browns and yellows and oranges.

If you look at it enough, how he moves the camera is extremely deliberate and extremely effective. It’s almost like his friend Stanley Kubrick at times, like with a static camera that’ll just move a little bit or something like that. It’s a masterful, visually stunning movie. Unfortunately, the visuals are also paired with dialogue that was absolutely rejected out of hand. Even the most talented actor could say some of the lines that are in the film and have it come out as anything but silly. There’s only so much you can do, but it still is in its own world. If you really buy into that world, if you completely embrace it, the movie just totally works.

Discussion