Interview: Roger and James Deakins on Cinematography and Navigating a Changing Film World

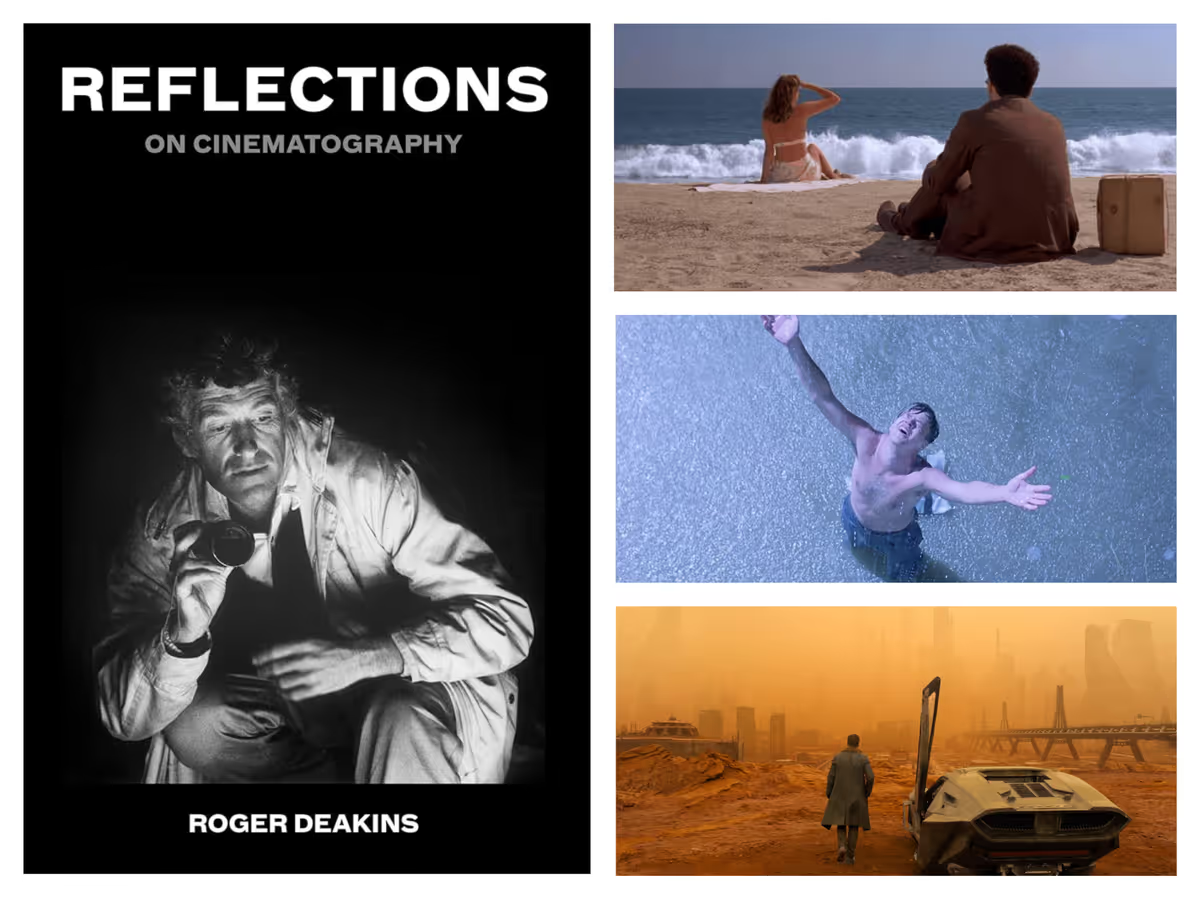

The master cinematographer and 16-time Oscar nominee reflects on a new book and a life in movies.

For decades, it was widely understood that Roger Deakins was one of the greatest cinematographers alive, but it took so long for him to win the Oscar for Best Cinematography that he was like the Susan Lucci of his field, racking up 14 nominations before finally winning for 2017’s Blade Runner 2049. (He then won again two years later for 1917, and now has a staggering 16 nominations in all.) His journey in film, however, began as a cameraman for documentaries that took him to far-flung places across the globe, including a nine-month stint aboard a yacht (Around the World with Ridgway) and two docs in Africa about the Rhodesian Bush War (Zimbabwe) and the Eritrean War of Independence (Eritrea– Behind Enemy Lines). His breakthrough in feature filmmaking came in 1983, when his experience on music videos and the British miniseries Wolcott drew the attention of director Michael Radford, who hired him first for Another Time, Another Place and then for his ambitious adaptation of George Orwell’s dystopian science fiction Nineteen Eighty-Four.

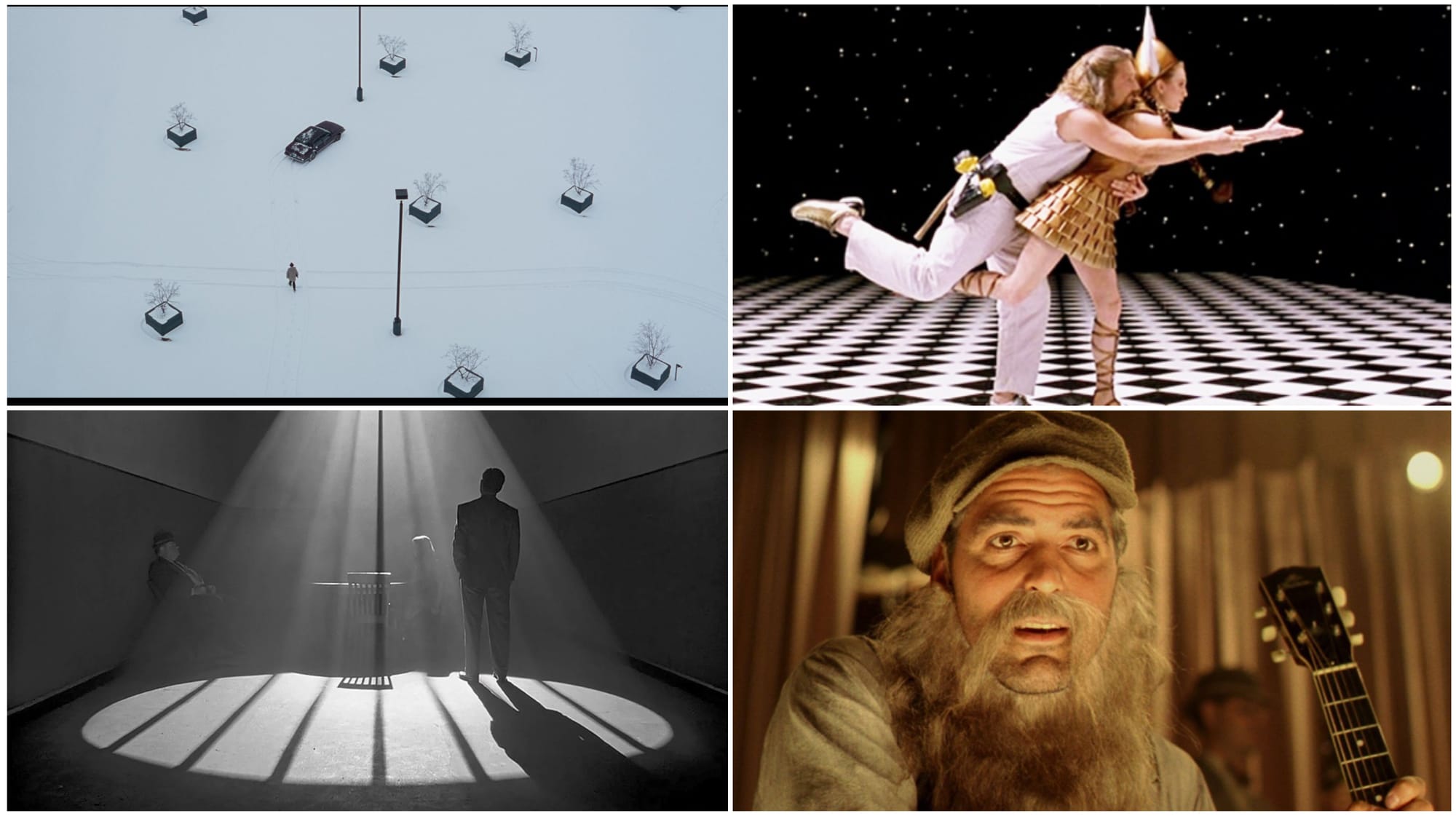

Though Deakins would continue to establish his reputation in Britain with films like Sid and Nancy and Stormy Monday, one of the most significant shifts in his career would come in 1991, when Joel and Ethan Coen hired him to shoot Barton Fink. Their collaboration would extend through 11 features total, with Oscar nominations for Fargo, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men and True Grit. Deakins has enjoyed partnerships with other major filmmakers, too, most notably Sam Mendes (Jarhead, Revolutionary Road, Skyfall, 1917, Empire of Light) and Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Sicario, Blade Runner 2049). Other memorable Deakins credits include The Shawshank Redemption, Kundun, The Village, and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward John Ford.

Deakins’ insights into his life in movies are now collected in Reflections: On Cinematography, a sumptuous new book that’s full of illustrative detail about his work but accessible to a broader readership. (Our own Keith Phipps assisted Deakins in shaping the material.) The book also owes much to his wife and longtime creative collaborator, James Ellis Deakins, who met him while serving as a script supervisor on the 1992 film Thunderheart and has worked alongside him on innumerable projects since. One of those projects, Team Deakins, is a popular podcast about the art of cinema in which Roger and James talk to a range of filmmakers, most recently Edgar Wright and Cristian Mungiu. The Reveal recently spoke to the Deakinses about their vision for the book, how they choose their projects and why Roger works so well with “the boys,” Joel and Ethan Coen.

What led you to write this book and what did you learn about yourself in the process of writing it?

Roger Deakins: I never intended to write a book, but a publisher approached us and asked us about it and offered to support it. I couldn’t really turn it down. James and I did a book of photographs [Byways] that came out of the pandemic and we arranged to get that published, but it was very difficult. We kind of had to part pay to get it published. So the idea of having a publisher support a book about my life and work was good. And like with our website and the podcast, we like to give back as much as we can.

What sort of reader did you have in mind? What did you want to communicate to them about the craft of cinematography and of your life in film?

RD: I was writing it for myself when I was 16 or 17 years old and didn’t have a clue what I wanted to do with my life. Hopefully it’s inspirational and it’s educational, but mostly I wanted to make it feel like the film industry is accessible to anybody who puts the effort in and the time in and has the passion for it.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. If you are not paid subscriber, we would love for you to click this button below and join our community.

Was it a challenge to give readers an idea of the technical aspects of filmmaking while also making it accessible to them?

RD: Yeah. We weren’t sure whether the publisher wanted actually something that was more of a tell-all book about Hollywood. They certainly wanted it to be about a small number of films, right?

James Deakins: Yeah. To begin with.

RD: They wanted [the focus on a] small number of films that people knew, like The Shawshank Redemption and stuff, and that wasn’t what we were interested in. But they were very supportive and allowed us to expand it, not only in format size, but in numbers of pages.We were also very keen on it being a reasonably priced book so that it would be available to students and people interested in film that didn’t have a lot of money, put it that way.

It looks expensive. There’s so much visual material in the book that you draw from your own preparation and also the illustrative images from the films themselves.

RD: That was important, too, the number of images and the diagrams. And on the one hand, we didn’t want it technical. But on the other hand, we didn’t want to be a sort of tell-all about the film business. So there was a kind of balance. I felt I wanted to reflect my thinking and my luck at getting into the industry.

So there are a couple of words that sort of stand out in the book that seem to define your process. One of those words is “naturalism” and the other one is “simplicity.” I was curious if you could help define for our readers what you mean by those two terms.

RD: As I say in the book, I think what’s natural is…

JD: To create a world.

RD: Yeah. To create a world that the audience is transposed into without one shot or a scene or one moment taking them out of that world. Now that isn’t to say that everything has to look like the world we see around us right now, but it has to be a believable world. It has to feel natural. As for “simplicity,” I think a lot of filmmakers, certainly a number of cinematographers, tend to throw it all against the wall. And I think the lighting and the camera movement and stuff can just be too ornate. To me, that’s really distracting. There are moments when it works to have a certain kind of lighting effect that in one film looks right, but in another film would stand out as being ridiculous. In some films, you can do a lot of moving camera and crane shots or something, but in another film, that doesn't really sit right. It takes the audience out of the world that you’re trying to create.

How does that end up applying to a conceit like, say, 1917, when you are doing something that is technically complicated and the audience is aware of it? How do you apply that principle of cinematography to a project like that?

RD: You try and make it so that the technique and the technology is…

JD: Invisible.

RD: Yeah, it’s invisible. It's not upfront. The nicest thing with 1917 is that coming out of the screening and hearing people say, “Oh, I didn't realize it was a single shot.” They were immersed within the story. I think because the film had a lot of publicity as a single shot, that was a distraction. But for the most part, if people hadn’t known that before they went in the cinema, they wouldn’t necessarily be aware of it. The idea of the single shot was that Sam wanted just to really involve people in the real-time development of the story. And it’s a simple story that does take place in real time, eventually around one character. I don’t think that’s a technique that you could really use on a lot of films. It’s a very particular style for that film.

So the two of you met during the shoot for Thunderheart. There was obviously a romantic spark, but how did your creative partnership evolve?

JD: I think because we were working on this project together and our goals were the same, so we wanted the best thing for that. And I was his script supervisor and we would talk about editing and which angle might work and things like that. We developed this really great working relationship first, which makes it really easy for us when we’re working because we may be doing something personally and then a work issue comes up and we just flip over to work.

RD: In a way, it’s not work. We kind of live our lives and sometimes we’re working on a movie and sometimes we’re figuring the book out or we’re doing the podcast. Like this morning, we were recording a session on an episode for the podcast. We just enjoy experiencing these things together. As the film industry changed, James was experienced in the lab, so she would become very involved in the process of the film development and post-production. And when digital became a big issue, when films were basically finished in a DI [digital intermediate —ed.] and all the effects work started to come into even a basically simple film, then there was much more to do, wasn't there?

JD: We also complement each other. I like talking to people. Some people don’t like it so much. [Laughs.]

RD: No, I’m kind of a private person, but James is much more gregarious.

JD: I like solving problems, and there’s always a million of them. So it’s a great challenge. I like that.

Given your experience and your reputation, I’m sure you’ve had a lot of decisions to make over the years about what jobs to take and what jobs to turn down. What factors tend to go into those decisions for you?

RD: Story, story, story. And then you’ve got to figure if you and the director are on the same page. It’s all right reading a script that you might like, but then the director might have a different take on the material. You want to be able to work with somebody that you can relate to and feel that you’re, again, like us, complementing each other as director and a cinematographer.

JD: It’s a long process, too. You have to be careful before you get into it because it is a personality thing, too. Is this going to work for six months? Are we going to be able to communicate?

RD: I’ve never thought of it as a job. I’ve always had a problem about work and…

JD: About the idea of work?

RD: Yeah. When I was growing up, I didn’t want to get a job. And so I went to art college and then film school and suddenly I’m in the film industry. I’m working as a cinematographer, but I didn’t feel like it was work. It’s important for me that I have that feeling when I’m on a film, that it's something I can really relate to and put all my passion into.

So the script and story ends up being a more important factor for you than, say, who the filmmaker is.

RD and JD (in unison): Oh, yeah.

RD: As I said in the book, I did walk away from the industry one time having a bad experience on a film [Air America], a film that I thought could have been really fantastic. I’m passionate about it, but there’s a level that I can walk away and say, "Well, I don't need this. There’s more to life than... You know?”

There’s a funny anecdote in the book where you talk about the terrible experience you had working with Roger Spottiswoode on Air America and how it actually helped you land what would be a life-changing job on Barton Fink. How did you end up clicking so well with the Coen Brothers?

RD: I don’t know. We did 11 films together. Similar sensibility. I think they wanted somebody that would just sort of like…

JD: Get on with it.

RD: Yeah, get on with it. Take control of shooting the film. They would have a very, very specific look and idea in mind. They knew what they wanted, but they want somebody that would just take that and get on with it. I think it’s as simple as that. Again, why do you get on with people? I mean, I’ve worked with somebody that I get on with very well socially as a friend but found it really hard working with them as a director. How do you know?

JD: The boys, the Coens, are very similar to Roger. They don’t talk a lot. They are happy being focused. They like a quiet set. These are all things that other directors might not like so much, so it’s just worked.

Is it helpful for you to have filmmakers who storyboard, who have things really mapped out in a very specific way in terms of angles and shots and all that? Does it matter?

No, no. I like working any which way, really. The first film I shot for Sam Mendes [Jarhead] was shot all handheld and we just basically shot rehearsals. And Sid and Nancy was very similar years before. I come from documentaries, so I like that sort of instinctive reaction to something that’s happening in front of me. That’s kind of why I like still photography now. I think it’s great doing storyboards. It’s great doing all that prep. You know then what the key elements of the scene are, what you really need to achieve in a day’s work. But to be kind of locked into them, I think, is a mistake. It’s not like painting by numbers. You’re not just filling in the spaces with images. It’s got to be more fluid than that.

JD: Just so long as you prep and you discuss the script and everybody’s on the same page, there is something fun about flying by the seat of your pants and going, “Let’s figure it out when we’re there.” But you do need to know what you’re going after, so you’re not discussing that on the set. You’re just discussing how to get the day.

RD: It can be really exciting not to have a plan and just work with the actors and the location and the way the natural light’s going or whatever. I don’t feel anxious on a set, not thinking that I won’t be able to come up with an idea for coverage of a scene. I think that’s exciting. But on the other hand, yeah, I like having storyboards. I really like prep time. I loved working with Denis Villeneuve and discussing the shots and the feel of the set, the look of the place and how you could do things with images rather than some of the dialogue. That kind of conversation, it’s quite great.

Did it take time for some of that fear to go away? You're given such a massive responsibility for the look of a film.

JD: So you're assuming that it goes away. [Laughs.]

RD: I find it incredibly stressful, whatever. It’s a big responsibility and the stress never goes away. But I think if you didn’t feel the stress, it would be because you weren’t really putting your all into it. You know?

One situation I'm thinking of in terms of stress that you write about in the book is the look of O Brother, Where Art Thou?, where you are filming a significant amount of that movie with an idea, I think, about how you wanted it to look, but not really necessarily being all that certain of what it was going to turn out when it was processed. Can you talk about that whole situation?

RD: Yeah. I mean, the funny thing about it was we had shot some tests. We decided we had to go with a digital finish, but obviously, it was in the days when this was very, very new technology.

JD: It was a leap of faith.

RD: Yeah, it was a leap of faith to start the movie and think, “Well, by the time we finish, technology will have caught up and we can do what we want to do.”

In terms of technology, you’ve certainly been around for a lot of great developments. Do you have to overcome any instinct to dig in your heels and want to shoot films a certain way, in a certain style, in a certain format?

RD: No, not really. There’s quite a few people who insist on shooting film and insist on large format, particularly this year. I mean, that’s fine for a particular film. Maybe in my ideal world, I would’ve been a cinematographer in the ’50s and early ’60s. I would’ve loved to just be shooting black-and-white and really, really simple with no video assist and none of all this stuff and no CGI effects. I loved doing things in camera. Like I say in the book, everything in Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was one of the first movies I shot, was all done in camera and that’s a tricky kind of filmmaking. I’d have loved that simple world, but it’s not like that now. We’ve talked on our podcast to cinematographers who create most, maybe 50% of the look or more, in the post process.

But that’s not me. I love photography. I love the reality, what's in front of me. But I can understand what they’re doing and I can appreciate the effect that they get. Technology’s constantly changing. You can’t stop it, can you? I’m not a Luddite. I might be nostalgic, but I’m not a Luddite.

We were talking about the Coens and I wanted to ask a little bit about the shooting of Fargo, which has this distinctive snow-white noir look. You have shots like Jerry (William H. Macy) returning to that empty parking lot after a meeting gone wrong, or Carl (Steve Buscemi) burying this money out in the middle of an endless unmarked landscape. What do you remember about those shots?

RD: In the book, [I write about] the parking lot where Jerry goes out to his car. That was storyboarded as a top shot, but the parking lot should have been full of other cars. And in fact, production brought in these extra cars and we were going to park them all in the lot. I was trying to get the glass taken out of a window so I could put the camera out and get the high shot from the top of this tower block. I looked at this sort of lonely car because they had put Jerry’s car in position for the shot. And then I called the assistant director and I said, “Let's stop everything now. Just let’s ask the boys, Joel and Ethan, to come up and look at this shot.”

And they came up and looked at it and said, “Well, yeah, I see what you mean, but what are we going to do with all the cars we brought in for the shoot?” And I said, “Well, I think we ought to ignore that.” So that's why the shot is just this one car. It doesn’t make any sense at all because it was meant to be a lot for people working in the office block, but it was funny. That’s the type of thing that can happen on the day of a shoot. You get a feeling from something you see, something that might be different than what you imagined sitting in a pre-production space with a pencil and a piece of paper. Things change, hopefully.

Keith tells me that shooting at a bowling alley for The Big Lebowski was not the easiest assignment you've had.

RD: Yeah. There were a lot of tricky things about that. As I say in the book, there’s one sequence in that bowling alley where there was a diagram of how we lit it and everything. The guys wanted to shoot slow motion. But the location they’d chosen was already very, very dark and most of the fixtures were caked in years and years of dirt. So there was hardly an exposure to start with, but when you’re shooting high speed, obviously you need more light. And the whole feel of the place needed to look quite downmarket, but glitzy. So that was quite a challenge, but also the shots they wanted were tough. Sometimes you kind of overthink it. We brought in a little model racing car and mounted the camera on it to do those tracking shots down the bowling alley, but it just didn’t work.

There was no control over the timing of it. So a Dolly grip I’ve worked with for 30 odd years, Bruce Hamme, said, “Oh, I’ll just put the camera on a soft pad and push it with a 40-foot scaffold pole.” And he did, and it was perfect. We had it underneath the girls for the dream sequence, as the camera goes between their legs down the bowling alley. It was perfect.

It took a famously long time for you to finally win an Oscar after so many nominations. I was watching the clip of you getting that first award and getting quite a huge ovation from the crowd that knew it had been quite some time. What did that feel like at the moment? What are your memories of that night?

RD: It was kind of unreal, really. I actually mostly remember just looking at the faces of people I’d worked with and that made me feel a bit more comfortable because it’s very nerve-racking doing something like that.

JD: It was great because the crew was really happy and I must have gotten over 1,000 texts and I answered them all that night.

RD: Yeah. A lot of the crew were upstairs and they were all kind of cheering. It was great. We did it together. A lot of people that were on Blade Runner I’d worked with for 30 years, so it was nice for everybody. But to me, some of the best films have never been nominated and some of the best cinematography is long forgotten, which is sad, but we all have different opinions.

Do you think there's a lack of understanding, I suppose, of what great cinematography actually is?

RD: Yeah. Well, as I've always said, I think the best cinematography is invisible because you’re immersing the audience within the story. But sometimes movies take a long time to be discovered. I mean, The Shawshank Redemption completely bombed at the box office. Now, why was that? It didn’t get any traction at all, but people say it’s one of their favorite movies of all time now. Which is strange, right? So if you want a film that didn’t get kudos and didn’t get box office, that’s it. How to account for that? I don’t know.

How did the podcast get started and how has that evolved into what it’s become now?

RD: It’s all James’ fault.

JD: We were doing a lot of Q&As for 1917. And at the end of the Q&As, oftentimes people would come up to us and ask the same technical questions. And so, I said to Roger, “Well, maybe we should just do a podcast that answers these questions.” And Roger went, “Hmm, what’s a podcast?” [Laughs.] And I didn’t really know much more, but we figured, well, we’ll do that. Then lockdown came and all these people happened to be around. And so, it sort of expanded on itself and it found its own way, which was basically a conversation. And it wasn’t a specific topic that we go in with. We just go in and want to have a conversation with them. And it was fun.

RD: When it started off, we were just going to talk to people that we’d worked with and talk about working relationships and the kind of work we’d done together and stuff like that. And then, as James said, it just expanded during COVID. And I think one of the key elements for us is the idea that film is a collaboration. So we like talking to a wide variety of people. It’s not just directors or actors. We try and talk to people right across a film set. Again, it’s something that me as a teenager would’ve liked to have heard, especially the idea of where you start. Everybody seems to have got into film from a very different way. Some obviously are born into it in Hollywood, but the majority come from a really disparate range of places.

Empire of Light is your most recent credit as cinematographer. Have you taken a step back? Do you intend to return to filmmaking?

JD: We’ve been very busy. We’ve had a lot going on and we’ve been having a lot of fun with it.

RD: Yeah, we had the book, but also we’ve been doing some photo exhibitions. I had that book of still photographs published, as I was saying, and…

JD: It’s just been fun. We do what we want.

RD: Yeah. There’s more to life than a film set.

Discussion