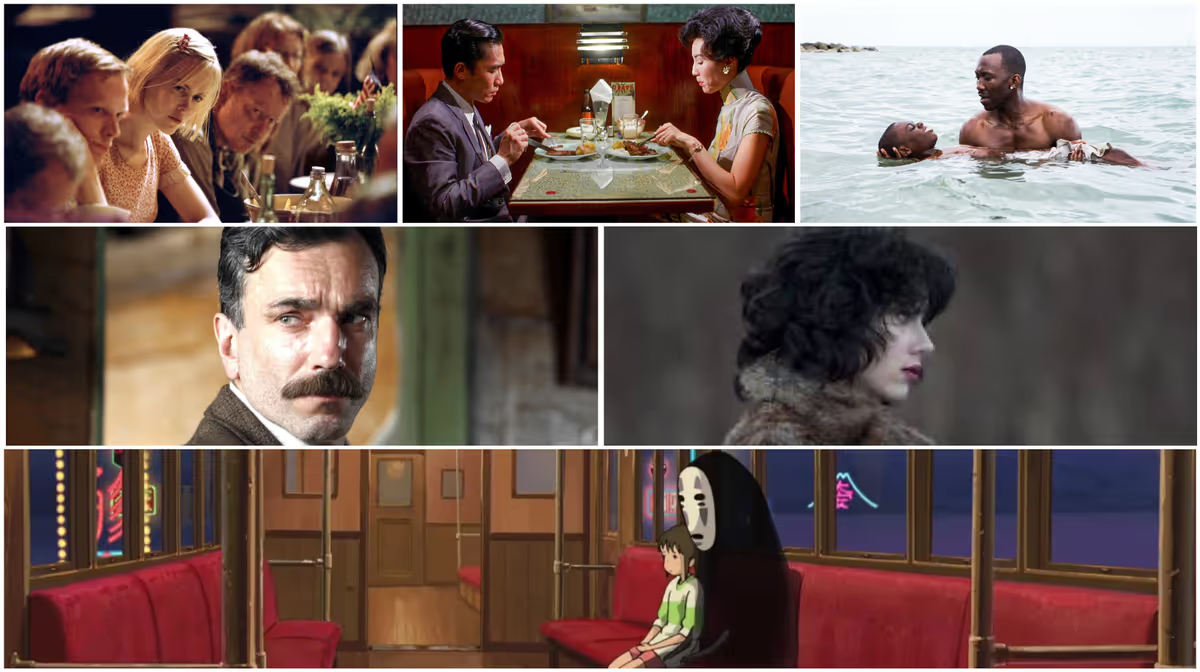

The 30 Best Films of the 21st Century — Part 2: #15-#1

The 21st century has produced many remarkable films. These are the 15 that mean the most to us.

Yesterday, we inaugurated our new platform, Ghost, with the first part of our 30 Best Films of the 21st Century list. As we explained in the intro to that piece, the ranking was part of a literal kitchen-table process where we went over our individual, unranked lists of 30 and came together on the order. We’re not mathematicians, but we do understand enough about numbers to recognize that tallying two ballots is not the optimal path of making a consensus list, so we had to have an old-fashioned conversation about it. This was a murkier process for the first half of the list, because there wasn’t any overlap and we had to go title-by-title to determine what made the most sense to us. And even then, the omissions were so painful that we have chosen not to include the dozens of “honorable mentions” that didn’t make the Top 30, because the entire conversation would likely shift to the modern masterpieces that missed the cut. So if you have a favorite that didn’t make the list at all, please be assured that it was definitely #31 and we have deep regrets about leaving it off.

But with the Top 10 on today’s list, at least, there was overlap from both our original 30 titles, which felt a little like two people turning a key simultaneously to launch a nuclear missile. Even for critics as like-minded as we tend to be, sharing 10 favorites in common over 25 years’ worth of movies seems significant and hopefully adds a little weight to that part of the list. It can be hard to know, in the moment, how any film is going to look years into the future, but we’d be shocked if these singular works didn’t stand the test of time.

15. Zodiac (2007)

Dir. David Fincher

Why it’s here: There are so many reasons why Fincher’s mournful thriller about the hunt for the Zodiac Killer belongs on this list from its evocation of a dread-soaked Bay Area in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s to its trio of lead characters (played by Jake Gyllenhaal, Robert Downey Jr., and Mark Ruffalo) who follow the case long after its gone cold. But it stands out most as an obsessive movie about the nature of obsession, and thus the most Fincherian movie of the director’s career.

Movie moment: The opening five or six minutes are at once seductive and terrifying, gliding through a Vallejo, California neighborhood as the fireworks pop off on July 4th, 1969 and the Zodiac’s first two victims drive off into the night. The soundtrack segues from Three Dog Night’s “Easy to Be Hard” to Donovan’s “Hurdy Gurdy Man” and the eerie, dreamy mood darkens into a nightmare, as the couple parks in lovers’ lane and a stalker emerges from a black muscle car. “Man, you really creeped us out” is all one victim can say before the bullets fly and the incident reverberates throughout an entire era in the Bay. —Scott Tobias

14. Dogville (2003)

Dir. Lars Von Trier

Why it’s here: An abiding faith in mankind tends to be understood as a virtue in movies, but what if the arc of the moral universe doesn’t bend towards justice? What if “decent” societies are, in fact, full of self-interested hypocrites who are capable of cruelty and exploitation? Part of an “America” trilogy that ended one film short after Manderlay, Von Trier’s audacious subversion of Our Town, shot on a bare stage with painted outlines to represent a small community in the Rockies, has a pessimistic view of human nature that has, let’s say, aged well.

Movie moment: The Brechtian conceit of Dogville, where there’s a natural transparency to a town without walls, lends power to a scene where Grace (Nicole Kidman), a young woman hiding from the mob, has been exiled by her hosts and subject to terrible abuse. As one citizen rapes her, the event naturally occurs in plain sight to us in the audience, so the image of the other townspeople going about their business within the same frame underlines their sadism and complicity. They are not the “good honest folks” they purport to be. —ST

13. Parasite (2019)

Dir. Bong Joon Ho

Why it’s here: With clear eyes and black humor, Bong Joon Ho explores the deep divide between the lower depths and upper reaches of contemporary Korean society via a family that does whatever it takes to get by, sometimes with little regard for the law.

Movie moment: After her brother Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) scams his way into a job serving as an English teacher for the wealthy Park family, Ki-jung (Park So-dam) attempts to do the same by posing as art therapist for the Park’s youngest, a boy named Da-Song (Jung Hyeon-jun). With a straight face, Ki-jung, using the name “Jessica” (“...only child, Illinois Chicago, classmate of Kim Jinmo…”), wastes no time establishing an urgent need for her services by pointing out some disturbing elements in the “schizophrenia zone” of one of Da-Song’s drawings. What can be done? For starters, he’ll need four two-hour sessions a week at Jessica’s top rate. —Keith Phipps

12. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

Dir. Wes Anderson

Why it’s here: Wes Anderson followed up Rushmore, his breakthrough film, with this story of a New York family that includes a trio of siblings (Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Luke Wilson) who’ve never quite lived up to their early promise and the father (Gene Hackman) who attempts to ingratiate himself back into their lives by feigning a fatal illness. Once again balancing deadpan humor against emotional heft, the film sees Anderson’s signature aesthetic fully realized for the first time.

Movie moment: Richie (Wilson), a self-destructive former tennis pro, reaches New York via boat and waits for his “usual escort,” his adopted sister Margot (Paltrow) to meet him by way of a Green Line bus. When she (finally) arrives, time slows to a near-halt as the wind blows through Margot’s hair and Nico’s version of Jackson Browne’s “These Days” fills the soundtrack. Like the song says, neither are the sort to do much talking anymore, but it’s clear they’re happy to see one another, or at least as happy as they get. —KP

11. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Dir. Martin Scorsese

Why it’s here: Working from a memoir by convicted fraudster Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), the founder of a rogue Long Island brokerage firm called Stratton Oakmont, Scorsese stage a dazzling Fellini-esque carnival of excess that chronicles Belfort’s grotesque misadventures while tying his behavior to the buttoned-down fraudulence of his Wall Street rivals.

Movie moment: As the SEC and the FBI start sniffing around his operation, Jordan meets with an FBI agent (Kyle Chandler) on his yacht, where he’s not shy about showing off all the lobsters and ladies that his million-a-week in earnings can afford him. Jordan’s arrogance backfires when the agent discourages his attempt at a bribe and leaves the ship with a deepened resolve to continue his securities investigation. Unbowed, Jordan pulls out a giant wad of cash and rains these “fun coupons” down on the agent’s head, making it absolutely clear that the high life is a hell of a lot better than taking the MTA to work like a sap. —ST

10. Moonlight (2016)

Dir. Barry Jenkins

Why it’s here: Adapting a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, Jenkins’ sophomore film tells the coming-of-age story of Chiron (played at various ages by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes), who begins the film as a fatherless child of a neglectful mother in Miami’s Liberty City neighborhood. Jenkins keeps the focus tight on Chiron’s perspective, creating a sense of a closed-in existence that he’s desperately trying to see beyond, and occasionally can.

Movie moment: As a boy, Chiron (Hibbert) finds a seemingly unlikely father figure in Juan (Mahershala Ali), a local drug dealer who gives him the sort of attention and tenderness he’s never experienced. After teaching Chiron to swim, Juan tells him, “At some point you gotta decide for yourself who you’re going to be,” a message Chiron hears then wrestles with for the rest of the film. —KP

9. Under the Skin (2013)

Dir. Jonathan Glazer

Why it’s here: In a loose adaptation of Michael Faber’s novel of the same name, Scarlett Johannson plays “the Female,” an alien who harvests unsuspecting men in the greater Glasgow area by assuming the form of a beautiful woman. Director Jonathan Glazer offers a rare vision: a look at humanity from the perspective of a being fully removed from it, at least at first.

Movie moment: The Female will develop empathy, or something like it, over the course of the film, but it’s terrifyingly absent Under the Skin’s early scenes. In one, she watches two parents drown as they attempt to rescue their dog, leaving their crying baby on the shore. The Female leaves with the male swimmer’s body. Left behind, the baby continues to wail. —KP

8. Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

Dir. Kelly Reichardt

Why it’s here: With her austere, captivating Western, Reichardt builds on the tension between three pioneer families trying to cross through the Cascade Mountains in 1845 and the grizzled, arrogant guide (Bruce Greenwood) who may be leading them astray. Michelle Williams’ performance as an assertive woman who challenges the guide adds tension to a film that’s already attuned to the gnawing precariousness of survival.

Movie moment: Reichardt’s slow-burn style rebuffs any expectations of a shoot-‘em-up, but the stakes are nonetheless high, especially in a sequence where three wagons have to be dragged up steep, rocky terrain with no margin for error. The good news is that everyone is pulling on the same rope, literally and metaphorically. The bad news is that the rope won’t hold and nature will simply swallow the entire group alive despite their best efforts. The whole mission of settlers is to strike out and conquer the uncertain, unknown wilds of nature herself. But sometimes, nature has other ideas. —ST

7. There Will be Blood (2007)

Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

Why it’s here: In the midst of an oil boom in turn-of-the-century California, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day Lewis) makes his fortune as what little remains of his interest in the well being of others falls away. Loosely based on Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, it renders depiction of American capitalism in its rawest form as a monster born only to acquire and conquer.

Movie moment: Talking to a man claiming to be his half-brother Henry (Kevin J. O’Connor), Daniel reveals how little he cares for humanity. “I see the worst in people, Henry,” Daniel tells his drinking companion. “I don’t have to look past seeing them to get all I need. I’ve built up my hatreds over the years, little by little.” His delivery suggests Daniel knows he has yet to finish building them. —KP

6. Spirited Away (2001)

Dir Hayao Miyazaki

Why it’s here: Among Miyazaki’s greatest and most singular achievements, this gorgeous animated odyssey through a bathhouse operated and frequented by supernatural beings addresses themes of courage, friendship, integrity, and modesty, all tied to a little girl who’s in a transitional phase in her life. The entire film defies description yet operates in a seamless, magical dream logic.

Movie moment: The most celebrated sequence in Spirited Away sets its young heroine on a train across the water is pure cinema, a wordless ride from day to night with only the gentle sound of the tracks and Joe Hisaishi’s score to accompany the images. It feels like a lonely trip for her and the shadowy spirits on board, but that melancholy doesn’t suppress the beauty of Miyazaki’s pastels and the reflections on the water and the train car windows. The sequence comes at the perfect time in the movie, taking a moment before the final act to drink in the world Miyazaki has created while acknowledging the unsettled inner life of his protagonist. —ST

5. 25th Hour (2002)

Dir. Spike Lee

Why it’s here: Through an accident of history, Lee’s gripping drama about Monty (Edward Norton), a convicted drug dealer having one last night out before starting a seven-year prison sentence coincided with the aftermath of the September 11th attacks in New York. Lee uses that backdrop to add context and broader significance to a story of personal reckoning.

Movie moment: In a sequence that recalls Jesus’ extended dream of living a long and mortal life as a human in The Last Temptation of Christ, Monty considers the option of fleeing justice and striking out somewhere else, with a new identity and a new lease on life. In this alternate reality, he doesn’t have to face any consequences for his sins and he gets to grow old with his girlfriend (Rosario Dawson) and have a family. But ultimately, “The Last Temptation of Monty” ends with him taking responsibility for his mistakes. (As a side note, it really takes a lot to convince New Yorkers to leave the city under any circumstances.) —ST

4. Yi Yi (2000)

Dir. Edward Yang

Why it’s here: A wedding and a funeral bookend Edward Yang’s swan song, a sprawling film concerning the loves and other entanglements of multiple generations of the Jians, a middle-class family in contemporary Taipei. Using a single spot on the globe at a particular moment in time, Yang creates an expansive look at the recurring cycles of joy and pain at the heart of human existence.

Movie moment: In Japan, the middle-aged N.J. (Wu Nien-jen) reunites with his first love, Sherry (Su-Yun Ko). In Taipei, N.J.’s daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) goes on a first date with a boy named Fatty (Chang Yu Pang). Yang lets the two evenings overlap with one another, sometimes allowing N.J.’s memories of his long-ago relationship with Sherry. Life will soon take the two couples elsewhere (and reveal Fatty as something other than the gentle boy he appears to be) but for this moment N.J. and and Ting-Ting’s form a dramatic rhyme, suggesting that each generation must experience the same rites of passage before handing them down to the next. —KP

3. The Tree of Life (2011)

Dir. Terrence Malick

Why it’s here: Over the course of his career, Malick has staged grand philosophical reveries over settings like the Great Depression (Days of Heaven), the Pacific Theater (The Thin Red Line), and American colonization (The New World), but The Tree of Life is his film about everything, and it’s both as massive as Creation itself and as minuscule as a newborn’s fingers.

Movie moment: The Tree of Life is a personal film for Malick, coalescing around a family in Waco, Texas in the ‘50s, where a couple (Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain) have diametrically opposed approaches to raising their three sons. Would anyone expect to see a dinosaur in this scenario? Or the Big Bang? Malick’s willingness to conjure these epochal events in human history in order to express something about human life takes him far out on a creative limb, where he successfully beckons us to join him. —ST

2. In the Mood for Love (2000)

Dir. Wong Kar-Wai

Why it’s here: Hong Kong, 1962: Su (Maggie Chung) and Chow (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai), both transplants to the cosmopolitan colony, come to realize that their spouses are having an affair with one another. As an attraction blossoms between them they hesitate while deciding whether or not to act upon it, a drama that plays out in a mesmerizing, dreamy haze of languorous routines, unspoken desires, and yearning pop music.

Movie moment: It’s hard to single out a moment in this film. One moment flows into the next and details fall in and out of focus, like elements of memory that the mind can’t quite fully recall. It’s sometimes not even clear where Su and Chow’s playacting of their imagined versions of their spouses’ indiscretions end and their own feelings begin. Except sometimes Wong makes it easy, as when Su collapses into Chow’s arms crying while he assures her that what they’re experiencing is not real. But the look on his face tells a different story. —KP

1. Mulholland Dr. (2001)

Dir. David Lynch

Why it’s here: What began as a rejected television pilot became the defining film of David Lynch’s career, a fearful love letter to movies and other invented narratives, including the stories we tell ourselves.

Movie moment: At the film’s turning point, its heroines, the new-to-Hollywood aspirin actress Betty (Naomi Watts) and the amnesiac Rita (Laura Harring), go to a sparsely attended nightclub called Club Silencio, where they’re told everything they’re about to experience is an illusion, from the sound of the orchestra to the thunderstorm. Both Betty and Rita respond fearfully. When singer Rebekah del Rio takes the stage to perform a heartbreaking rendition of “Llorando,” a Spanish-language version of Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” both are moved to tears (as, perhaps, are those watching the film). When del Rio collapses, the song keeps playing without her, shattering the illusion. But the melody and the emotions it stirs still linger. —KP

Discussion