When the Coppolas Went Downriver

A new 4K rerelease of 'Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse' reveals the madness to Francis Coppola's method.

“My greatest fear is to make a really shitty, embarrassing, pompous film on an important subject, and I am doing it.” — Francis Ford Coppola

“I swallowed a bug.” — Marlon Brando

A tale of two movies shot in 1976:

On November 25th, 1976 at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, the Canadian roots-rock act The Band staged a lavish farewell concert with musical guests that included Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond, Emmylou Harris, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, and Neil Young, among others. Director Martin Scorsese, a friend (and later roommate) of The Band’s guitarist and chief songwriter Robbie Robertson, brought a crew of first-rate cinematographers and recordists to make a feature film out of the event, which would become 1978’s The Last Waltz, widely considered one of the greatest concert films ever made. And while a live show like this one can (and did) include many spontaneous moments, Scorsese treated the assignment with the same granular attention to detail as he did his other feature films. He anticipated the set list and choreographed the camera movements as if he were conducting a symphony, trying to maximize all the high notes that he could.

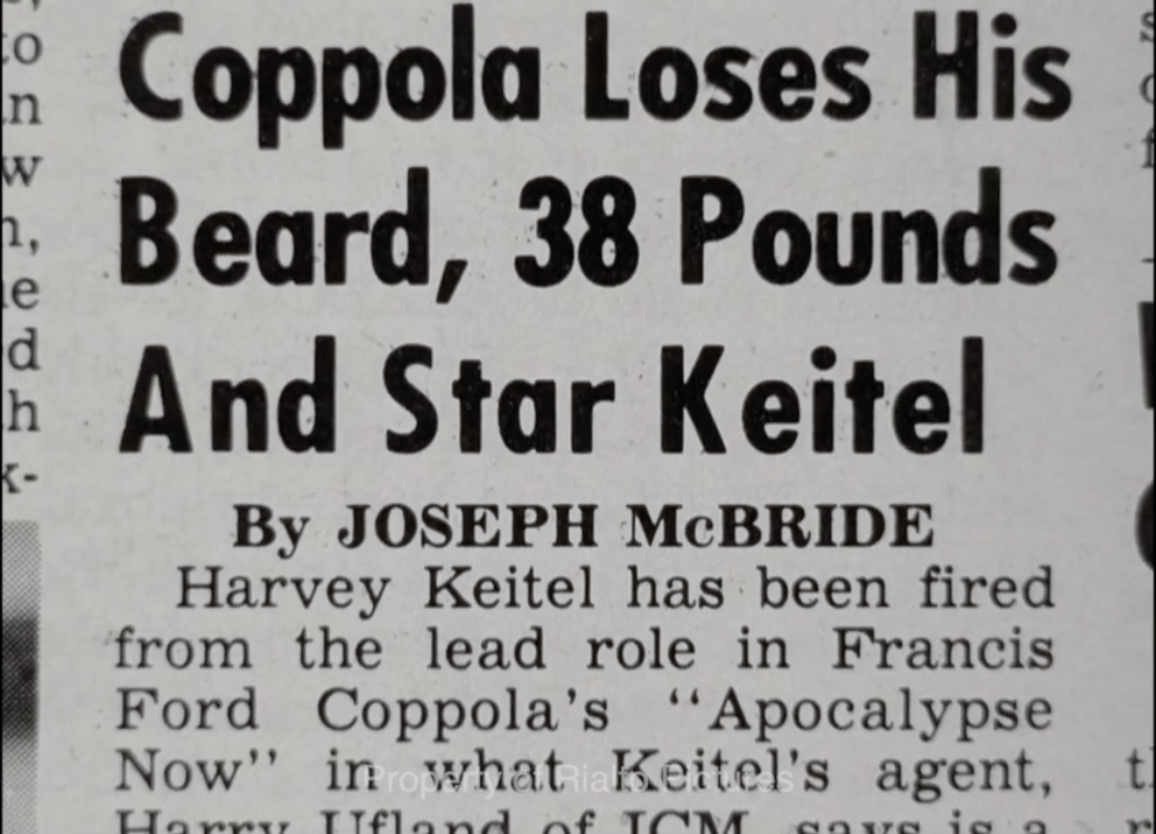

Earlier that year, in February 1976, Francis Ford Coppola and his family moved into a house in the Philippines to start production on Apocalypse Now, his loose adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness, conceived as an allegory for the Vietnam War.* Producing through his company American Zoetrope, Coppola raised the $13 million budget himself (half from United Artists, half from international sales) to maintain creative control, but he also put his personal assets up as collateral. The shoot was intended to last four months, but production wrapped after 238 days of principal photography and the film wasn’t released until the summer of 1979. Some of the catastrophes were out of Coppola’s hands, like a typhoon that ripped through many of the sets and sent the cast and crew back to America for a couple of months, or a heart event suffered by the film’s star, Martin Sheen, who needed time to recuperate before he could get back to work. Other disasters were simply endemic to Coppola’s process, which involved constant rewrites and improvisation to “discover” the film that eventually emerged from the chaos.

This is not to suggest that Scorsese’s level of preparation squeezed the organic life out of The Last Waltz or that Coppola and his crew arrived in the Philippines without any plans to upend. But there is a stark distinction here between a film that is planned and a film that is discovered. Scorsese had to puzzle through the logistics of capturing a one-night-only event, which had no second takes; Coppola had granted himself seemingly limitless takes on Apocalypse Now, which he understood as a film full of philosophical “questions” that he would seek to answer. It could only be planned to a point—and even then, forces of nature like a typhoon and Marlon Brando could not be contained—because the experience of going downriver was crucial for everyone: Coppola had to journey into his Heart of Darkness. So did the cast and crew. And so does the audience. It couldn’t feel precooked.

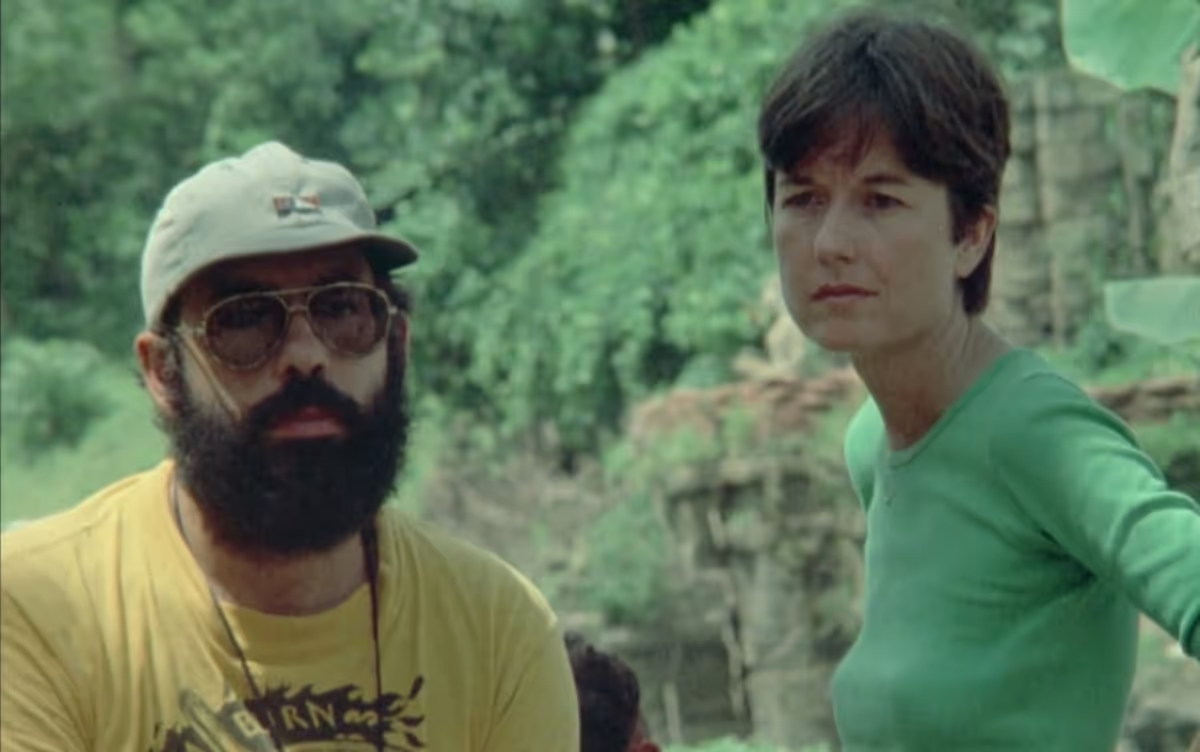

A 4K restoration of Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, the great 1991 documentary assembled around footage shot by the late Eleanor Coppola, opens this week at Film Forum in New York, and it’s a good opportunity to appreciate Coppola’s essential audacity. Directed by Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper, with Eleanor contributing bits of narration when necessary, it ranks alongside Les Blank’s 1982 film Burden of Dreams, about the exceedingly troubled production of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, as the most compelling making-of doc ever made. The two films overlap so closely that their echoes are uncanny: Two auteurs in the jungle, eager to take an experiential approach to real historical events, go as mad as the heroes at the center of their stories. They smack against obstacles both uncommon and self-imposed, and come away questioning the value of themselves, their work, and the artistic process writ large. (They also benefit from cheap indigenous labor, though it’s hard in either case to put that in the plus column.)

This post is for paying members only

Sign up now to read the post and get access to the full library of posts for subscribers only.

✦ Sign up