#60 (tie): ‘Daughters of the Dust’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Julie Dash's landmark independent film captures a Black community at a turning point.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Dir. Julie Dash

Ranking: #60 (tie)

Previous ranking: N/A

Premise: In 1902, members of the Peazant family prepare to leave their home on Dataw Island, one of the Sea Islands off the Georgia coast, for the mainland and life in the north. This means leaving behind a unique Gullah culture in which Western and Christian traditions have been blended, not always harmoniously, with African beliefs and practices. The move inspires contrasting feelings in the family. Nana (Cora Lee Day), the family’s matriarch, is reluctant to leave. Viola (Cherly Lynn Bruce) and her cousin “Yellow” Mary (Barbara-O) have returned from the mainland in the company of a photographer named Mr. Snead (Tommy Redmond Hicks) and a woman named Trula (Trula Hoosier), who appears to be Mary’s lover. Eula (Alva Rogers) and Eli (Adisa Anderson) are preoccupied with Eula’s pregnancy and the child who might be the result of her rape at the hands of a man she won’t name. (Eula’s child, billed as the Unborn Child (Kai-Lynn Warren), provides occasional narration and sometimes appears as a fantasy figure.) Iona’s (Bahni Turpin) love for the Cherokee man Julien (M. Cochise Anderson) has her pondering whether or not she can go. As they prepare, the film explores the life they plan to leave behind and consider their hopes for the future.

Keith: Daughters of the Dust writer-director Julie Dash opens her film with a pair of title cards explaining the origins of the Gullah communities that populate the islands off of South Carolina and Georgia, but the film otherwise invites viewers to figure it out for themselves. We get glimpses of elements of island life that are never explained in full. Here’s an example: in one shot, some of the children play a game that involves moving stones on a board with round depressions. I recognized this as Mancala (or some variation) only because the game has since been packaged and marketed to the board game market. (I think I first played it at your house, Scott, losing badly to one of your daughters.) It’s there for those who get it to appreciate—and I certainly didn’t recognize it the first time I saw this film—and makes the setting richer even if you don’t.

Here’s how Dash explained her approach to A.O. Scott in 2020:

We shared intimate stories [...] profound moments that connect us to the history of the diaspora — without explaining, without going all National Geographic. A meditative type of thing, structured the way an African griot would narrate a family’s history over days and days.

That accurately suggests the feeling of the film, which tells many sorts of stories piece by piece. It’s a film filled with many different characters. (My plot summary above doesn’t even mention Bilal (Umar Abdurrahman) a member of the island’s Muslim community or Haagar (Kaycee Moore), who’s disagreeable but willful and one of the forces pushing the migration). It also makes a great effort to capture how they live their lives with the bittersweet knowledge that, for many of the Peazants, this is the end of their way of life. It’s closing time at their home on Ibo Landing and nothing will be the same after today.

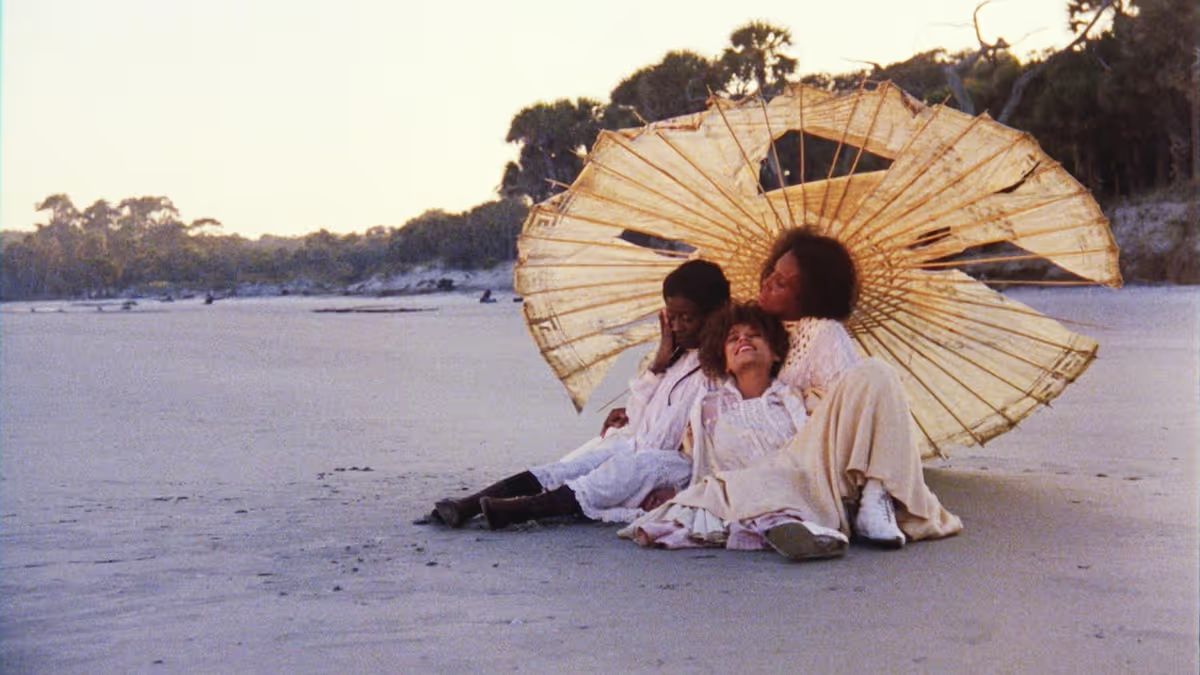

Daughters of the Dust is gorgeous and dreamlike . Dash and cinematographer Arthur Jafa (who’d go on to a long career as both a director of photography and a video artist) shot the film on location using natural light and they truly create a sense that they’re capturing a lost place and time. At the heart of Daughters of the Dust is a depiction of a unique, vibrant community whose creation is the result of enslavement and the horrors of American history. And, without feeling programmatic, Daughters of the Dust touches on sometimes harrowing ways Gullah culture intersects with the larger story of American history.

It’s a lovely, fascinating film. I also have found it a bit challenging each time I’ve watched it. Dash does something truly unusual with her languorous approach to storytelling. The film has one pace that it sticks to from start to finish and I suspect it’s my own expectations of how a film is supposed to move and the ways stories typically unfold that gets in the way of my ability to lock fully into that rhythm. It’s a film I would love the chance to see on the big screen, where I suspect it would play differently than at home.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

It’s hard to overstate the film’s historic importance. Daughters of the Dust is sometimes referred to as the first feature film directed by a Black woman, which isn’t strictly speaking true. Several Black women directed films in the early days of film. Kathleen Collins directed a 1982 film called Losing Ground that did not play outside festivals in her lifetime. (Collins died in 1988. I have not seen the film but I should seek it out.) It sounds really interesting. So technically, Daughters of the Dust is the first film of the modern era directed by a Black woman to receive a theatrical release. In 1991. That’s really recent. And it’s not like it’s now super-easy for Black women to make films and have them released, but a lot has changed since, and because of, Daughters of the Dust. Beyond that, it’s stylistically quite bold and influential. Much of the renewed interest toward this film stems from a restoration and re-release for its 25th anniversary. But at least some of it comes from Beyoncé’s Lemonade video album being filled with nods to Dash’s work.

Scott, how was your experience of watching Daughters of the Dust this time? And there are a lot of narrative strands to talk about. I’d love to hear your thoughts on Nana, who’s presented as both a keeper of traditions and, maybe, an inhibitive force on the Peazant family’s progress. I think one of the strengths of this film is to let a character not be merely one thing, just as its view of history is complicated and its attitude toward the migration at its center feels bittersweet. What was your read on her?

Scott: I’ll get into the Nana character in a bit, because she’s really the fulcrum of this whole family narrative and maybe the soul of the movie. But I wanted to start by talking a bit about my own tortured history with Daughters of the Dust, which seems to mirror yours a bit. I first encountered this film during its theatrical release, when we programmed it at the Tate Theater on University of Georgia campus while I was still a movie-crazy undergrad. I confess to being a bit flummoxed by it then, at least in engaging with its unusual rhythms and conceits, though the island setting, the costumes, and Arthur Jafa’s gorgeous cinematography stayed with me, along with the faces of Dash’s actors. Even when I saw it a second time a couple decades later, it remained a film I respected more than loved and I probably would not have returned to it were it not for this project.

Well, the third time turned out to be a charm. And I think a big reason is something you laid out above: Daughters of the Dust was, insanely, the first theatrical release of a feature directed by a Black woman. (Incidentally, I caught up with Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground when it was on Criterion Channel and likened it to “homegrown Eric Rohmer.” The early ‘80s were truly a fallow period for American independent cinema for that film not to get any play.) Put simply, Dash’s film is singular, which is why it now finds itself on the Sight & Sound list, along with the National Film Registry, which enshrined it quite a bit earlier, in 2004. When singular works of art first find their way out into the world, they’re not always well-received, for the obvious reason that nobody has experienced anything quite like it. And while Daughters of the Dust was kindly reviewed at the time, its poetic language and symbolism, its languorous style, and its cross-generational conflicts are difficult to parse. Even now, it might be good to advise those seeing the film for the first time to allow the images and the score to take them on a reverie, and just pick up whatever they can from the storytelling.

Daughters of the Dust feels like a feature made by a director who suspected she’d never get an opportunity to make another, which is exactly what happened, though Dash later found work in television and a few music videos. It’s a prismatic work about Black identity, particularly the plight of Black women, that uses its unique turn-of-the-century island setting to reflect on the past, present, and future of characters scarred by slavery, bound by ancestral traditions and values, and still seeking a place they can call home. And while the opening titles seem to celebrate the Gullah and their “distinct, imaginative and original African American culture,” the reality on the ground is much more unsettled, because this family is about to split apart.

Set over the course of one day—that early helicopter shot introducing Ibo Landing at sunrise is something else—the film would seem to be about a celebration, one last family reunion before the majority of these characters migrate from Sea Island to the north, where a more just and prosperous America presumably awaits. The photographer Mr. Snead has arrived with a camera to create official portraits of the Peazants before they depart, and a big feast with shrimp, corn, and okra is being prepared, which again makes it seem like a party when, in fact, it’s more like a funeral or an outright reckoning. Leaving the island may feel like an opportunity for some, but the cost of assimilation is steep, and we already see some tension building up between those who have spent time on the mainland like Viola, a Christian convert, and those who cling fiercely to the spiritual and cultural ideas brought over from Africa.

Which brings me to Nana Peazant, played by Cora Lee Day, whose anguished face burns into your brain. We’re first introduced to her when she’s having a heated discussion with Eli, who’s intends to leave the island, but is fuming over the rape that led to his wife’s pregnancy. Nana’s line “We carry these memories inside of we” seems to me the thesis statement of the movie, supporting this idea of an important continuity between generations dating back as far as Africa. (Or as Nana says, “They’re all the same, from the ancestors to the womb.”) Nana refuses to leave the island and seems determined to persuade others to stay, putting her in conflict with people like Viola, who seems to have turned the page along with others who have spent more time on the mainland. She warns that the north is “no land of milk and honey,” and while she’s resigned herself to Eli and Eula moving away, she wants him to keep his family together and continue to celebrate Gullah ways.

I’m curious, Keith, what impact do you think Nana ultimately has on the Peazants in the end? There’s a small faction who seem to think she’s hindered by those remnants of the past she keeps in a tin memory box, but it’s obviously significant that Eli, Eula, and our “unborn child” narrator ultimately decide to stick around. How do we arrive at this conclusion? And what is Julie Dash’s perspective on all this?

Keith: I think Dash, and the film, have the benefit of a perspective unavailable to any of the characters (except maybe the Unborn Child): the knowledge of what happens next. They’ll live in a 20th century of profound change, but also profound struggle. The North won’t be a land of milk and honey, but it’s also a place they can play a role in reshaping. The Sea Islands, for all the history they’ve experienced, seem destined to stay much the same or change at a rate too frustrating for those inclined to build new lives elsewhere. (As a side note, Dash followed the film up with a literary sequel, a novel of the same name set a decade after the events of the film, so anyone curious about what would happen next might get some answers there. Rewatching this has made me curious about it.)

But I don’t think Daughters of the Dust has any interest in those who leave or those who stay. As you point out, Dash took on an enormous task with this film, which uses one day in a particular time and place as a nexus point for many in-progress stories about the experiences of Black people in America. It’s a sweeping film in which distinctive individual characters alternately swim against or get swept along by the tides of history.

Nana belongs firmly in the “swim against” column, and Dash both depicts what she’s losing by refusing to move with her family (most notably, that family itself) but also what would be lost if she didn’t keep to the old ways. She’s the living memory of their time as enslaved people. She’s also getting up in years, so what happens to that memory after she’s gone? The habits she keeps to maintain those memories, namely that tin box, are already mocked as eccentric and would be tough to sustain elsewhere. But, left behind, she can pass these memories down to whoever stays.

The film’s final scenes suggest that everyone who leaves and everyone who stays has made a choice to accept some losses with their gains. That’s true for Eli and Eula but also for Bilal and Iona, who also remain for differing reasons. I sometimes wish the storytelling in this film was a bit less wispy but a more straightforward approach might have made the bittersweetness of the ending harder to achieve. The end both suggests history is huge and complex and contains overlapping eras that put generations in conversation with one another but also conveys a sense of one chapter definitively ending as another begins.

Scott, can I confess to a problem I have with this film? I think it’s sometimes undermined by John Barnes’ near-constant score, a mix of African rhythms and ‘80s new age music. It feels like pedestrian, particularly when paired with the stunning imagery. Did that bother you as well? On a more positive note, do you have a favorite sequence or plot strand? I’m fascinated by the journey taken by Mr. Snead, whose confidence about what he’s learned about history, which he seems to view as marching forward, is undermined by stories of the importation of enslaved people from Africa after it was made illegal. His conversation with Bilal that reveals the grim origins of a local folk tale is particularly chilling.

Scott: I’m glad you mentioned the score as a hindrance, Keith, because I think it does some minor damage to the film overall. Pulling this observation directly from my notes: “score is a combination of African tribal music and the new age stuff you’d hear while getting a massage.” It does blanket the film, as you say, but where it really stands out is when Dash cuts off the dialogue and wants the lingering emotions or Arthur Jafa’s imagery to carry the day. Daughters of the Dust happens to be a movie where the score is more important than it might be otherwise, because Dash is so committed to tweaking storytelling convention. She relies on the music to enhance the film’s strengths, but it undermines them a little.

To get back to the many things that work in the film, I like your point about the “Unborn Child” narrator and how much that allows us to think about what the future holds beyond this one day in 1902. While Eli and Eula’s decision to stay on the island means that their child ultimately won’t experience what those who leave will discover about “the land of milk and honey,” we certainly have an idea of the obstacles that await Black people during that period and beyond. The film seems to support Nana’s belief about the continuity between past, present, and future, and it also expresses, with extraordinary anguish, the pain of the Peazants breaking apart, even if it was inevitable and perhaps the right decision. (Though this one day, with its generous feast and island breezes, makes a good case to stick around.)

One critical aspect of the film we haven’t talked about yet is the sexual violence that binds Eula and Yellow Mary together in trauma and shame. It’s certainly worth noting that our narrator is the product of rape by a white man, and Eli’s anger over what happened to his wife spills over into their marriage and even into his relationship with Nana. He is going to be this child’s father, but he doesn’t yet seem prepared to embrace the role. What happened to Mary isn’t quite as clear, but she’s been spending her time on the mainland forging a more independent life for herself and trying to push back against the idea that she was “ruined” by her past. With her big climactic monologue around her family towards the end, Eula pleads, “If you love yourselves, then love Yellow Mary. She’s a part of you, just as we’re a part of our mothers.” The toll of sexual violence, on top of a larger history of oppression, is a heavy one for the Peazants to carry and you can see that solidarity is both essential and sometimes hard to achieve.

The other piece of Eula’s monologue that moved me relates to the “scars of the past.” She says, “We wear our scars like armor for protection” while also asking everyone to live their lives “without living in the fold of old wounds.” There are specific horrors that come out at various points throughout Daughters of the Dust—a woman forced to nurse a white family’s infant after losing her own during childbirth, a ship full of slaves in iron shackles sinking en masse to the bottom of the sea—and Dash registers the agony of these injustices along with the resilience to move forward, especially as they leave this place and scatter to destinations unknown.

Though we still have Killer of Sheep and “Meshes of the Afternoon” ahead of us on the list, I think it’s significant that Daughters of the Dust is such a high water mark for American independent cinema, particularly the Sundance era that transformed the arthouse landscape to such a huge extent post-sex, lies and videotape. It remains a true independent film from production to distribution, finding its way into theaters through Kino, a company that’s now been around for nearly 50 years, and it exists apart from the frenzied marketplace of the festival, too. It followed no model for what a successful indie might look like, and almost seems sui generis as a piece of filmmaking, quite apart from being a milestone in Black cinema.

It took a few decades for it to make the Sight & Sound list—it didn’t even rank in the Top 250 in 2012—but its placement is a truly proud moment for American film. I complain often about how often American independent films tend to dodge uncomfortable political or historical moments, and that’s to say nothing about the barriers that have faced filmmakers of color. Daughters of the Dust is a crucial anomaly, and it’s been rewarded for standing out.

Next up, we’re going back to Chris Marker after covering him a few months ago with La Jetée. And Sans Soleil will give us 72 more minutes of footage to analyze!

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

Discussion