#50 (tie): ‘The 400 Blows’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

François Truffaut's feature debut helped reinvent what movies could do with a personal story from the director's own troubled youth.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

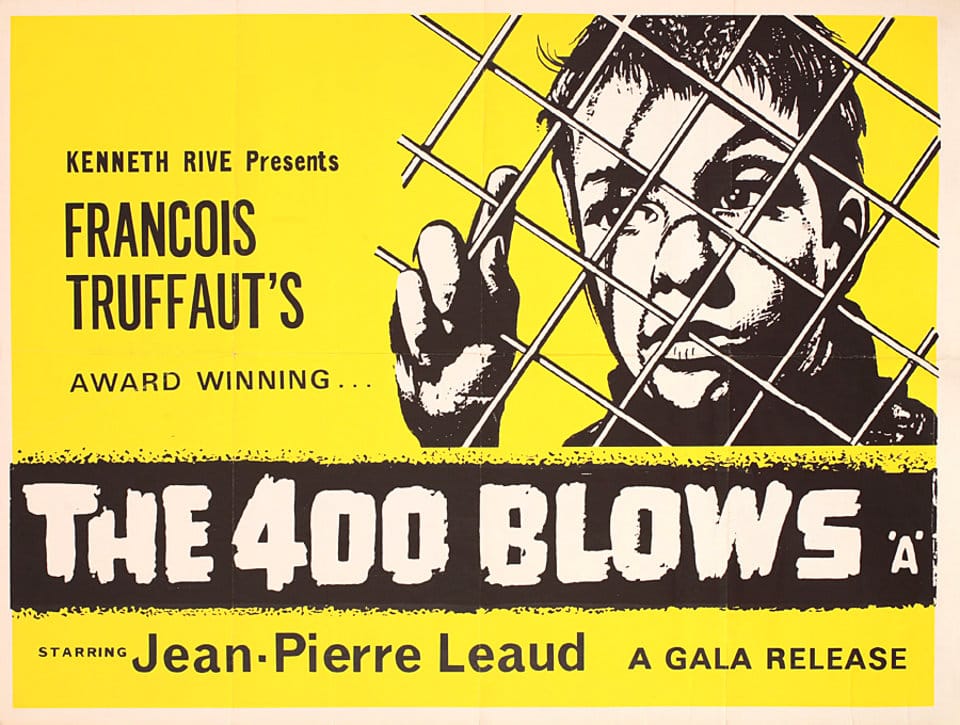

The 400 Blows (1959)

Dir. François Truffaut

Ranking: #50 (tie)

Previous ranking: #39 (2012); #37 (2002)

Premise: In Paris, young Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is a juvenile delinquent in the making. When we first encounter him, Antoine is getting punished at school for holding the calendar pin-up all the boys are passing around class, and he’s not the type to get the benefit of the doubt from his teacher. Along with his best friend René (Patrick Auffay), a fellow troublemaker, Antoine is shown skipping school, pilfering cash, and committing petty crimes, but he also loves going to the movies and keeps a shrine at home for Honoré de Balzac. At home, his mother Gilberte (Claire Maurier) and stepfather Julien (Albert Rémy) fight with him and each other, and their separate jobs free him from adult supervision. When Antoine decides to steal and pawn a typewriter from his stepfather’s office, however, the consequences for his actions are stiffer than he’s prepared to handle.

Scott: Just as I did in our last Sight and Sound conversation, on Jane Campion’s The Piano, let me kick us off with a sequence that I feel says a lot about what The 400 Blows is attempting and what makes it so special as a piece of filmmaking. After a long sequence where Antoine and René are causing all sorts of mischief together—going to the movies with stolen money and then swiping a sexy lobby card on the way out; smoking cigars and playing backgammon in René’s room; hawking spitballs they’ve made out of pages from the Michelin guide Antoine stole from his stepdad—Truffaut cuts to an audience full of younger children watching a puppet show in a public park. The children are reacting to the show with a surprise and glee that feels unusually authentic, a quick reminder that Truffaut was an unparalleled master at working with kids (see also: 1976’s Small Change a.k.a. Pocket Money) and a clear influence on Steven Spielberg in this respect, among others. The film takes its time to reveal that Antoine and René are sitting together in the back of the theater, plotting the typewriter theft that will ultimately seal Antoine’s fate. Then, the sequence ends with another long take of the youngsters giggling at the show.

It’s not exactly Advanced Cinema Analysis to see what Truffaut is suggesting here in contrasting the carefree fun of innocent children with our two adolescent schemers in the back, but the simplicity of it doesn’t make it any less affecting. Did Antoine ever have a childhood like those other kids? (We find out later that he didn’t, but I think we could safely presume it at this point.) At what point did life become so wayward and complicated for him? Children are supposed to be blameless yet Antoine is culpable for all his past, present, and future punishment, and Truffaut seems to wonder when he stopped being a child and became someone who needed a night in prison and a stint in an “observational center” to be set straight. At this puppet show, Antoine is framed as both a child among other children and the conspicuous plotter of a criminal scheme. So who is he to us?

Truffaut, who offered Doinel as a cinematic alter-ego over multiple films, obviously does not want us to dismiss Antoine as an irredeemable hoodlum. (Contrast that with the boys in Luis Buñuel’s 1950 film Los Olvidados, who are treated more starkly by the director for their brutality and violence, albeit not without sympathy for their lives in the slums of Mexico City, either.) By the time we get to the end of The 400 Blows, Truffaut has given us a complete picture of Antoine and the circumstances that have led him down this terrible path. But much of what’s great about the film is how much time it spends simply following his antics, which may include a lot of petty thievery and rebellion, but also show flashes of impish intelligence and wit. Here’s a kid who nearly lights his house on fire paying tribute to Balzac. He’s got potential.

There’s a lot to talk about here, Keith, given how important The 400 Blows would be in establishing the French New Wave and launching the career of a major director. But I’m curious to hear what you think about the film as an act of cinematic portraiture. It may be tempting to link The 400 Blows with something like Bicycle Thieves from a decade earlier as a social drama, but I don’t think that squares with Truffaut’s approach, which is more playful and not quite as plain in its agenda. It seems more like a slice-of-life that almost slips into a tragedy, much like Antoine slips into a situation far more frightening and despairing than he could have ever anticipated. What stands out for you here?

Keith: Between viewings of The 400 Blows I tend to forget the playfulness you’re describing. The film begins with Antoine unjustly punished for an offense others were committing alongside him—he just happened to be caught—and ends on a famously (and deeply influential) freeze frame of Antoine staring down an uncertain future. Then there’s the title, which to English-speaking ears seems to describe a time of unyielding punishment. (Alternate title: One Blow After Another?) And you can certainly see the film as depicting that, since Antoine gets into a lot of trouble. But the French phrase “les quatre cents coups” is closer to something like “raising hell” or “sewing wild oats,” and there’s plenty of that, too. Though it’s kind of strange that the film reached the English-language world with a title that distorts the intent of the original phrase, I kind of like it. It adds to the ambiguity of Truffaut’s depiction of a time in Antoine’s life where nothing is clearly defined and one minute’s bit of mischief can have considerable consequences moments later.

There is, as you point out, great fun here, largely because Truffaut immediately makes us sympathetic to Antoine as he navigates a world in which adults are some combination of oblivious, selfish, stupid, and cruel. Who wouldn’t want to duck that for a day watching movies and otherwise breaking the rules? It’s not a feeling unique to Antoine, either, as evidenced in the film’s funniest scene, in which kids peel off from a gym-class jog through the streets of Paris while their teacher cluelessly plugs along. Sure, their world is supposed to be limited by classroom walls, but there’s a whole city to explore. And since the adults around them seem to have no interest in adventure, they should probably get to it while they’re still young.

But it’s still the sadness that stays with me when I think of the film, in part because Antoine’s something of a reluctant rebel. He really wants to please his mother and stepfather but their interest in him waxes and wanes over the course of the film. As his troubles deepen, their love for him is revealed as highly conditional, a horrible thing for any child to realize. But there’s a stretch in the middle of the film where his love of Balzac gives him a way to engage with his studies for the first time and Antoine and his parents go to a movie and enjoy each others’ company that suggest his fortunes might be changing. Of course, it doesn’t last. His teacher doesn’t see any difference between Antoine paying homage to Balzac and plagiarism, an accusation that cascades until ultimately revealing how little his parents understand him (or care to try to understand him).

At the same time, it’s easy to see how exhausted and exasperated Antoine’s parents and teachers must be. His high-spiritedness translates as incorrigibility and his restlessness as stupidity. Truffaut's ability to make us see all sides of the story is one of the most extraordinary qualities of The 400 Blows, one made all the more remarkable by the film’s autobiographical elements. I was listening to Brian Stonehill’s audio commentary for the film on the Criterion Collection disc. Stonehill recorded it in 1992, when some of Truffaut’s childhood friends were still alive and could attest to just how much was taken directly from the filmmaker’s own childhood. And yet for all the injustice Antoine encounters, I don’t see the film as self-pitying. It’s moving but the style and restraint keeps it from being sentimental, an approach that feels key to it serving as a French New Wave touchstone.

We should probably talk about the film’s place in history, shouldn’t we? In Richard Linklater’s recent Nouvelle Vague, we see Godard watching his friend Truffaut’s film premiere with a mix of admiration and jealousy but also an understanding that he’s helped elbow open a door Godard could kick down. How do you see The 400 Blows fitting into that movement? And, circling back, does knowing how much Truffaut drew on his own childhood change the way you see the film? Or that the director helped give direction to Léaud’s life by casting him as the lead, much as Truffaut would credit Andre Bazin—to whom the film is dedicated—with giving him guidance as a youth? The 400 Blows contains a memorable shot of Anotine’s face reflected in mirrors that suggests the boys’ many facets but the film itself has mirrors within mirrors, doesn’t it?

Scott: How does The 400 Blows fit into the French New Wave? The catch-all word that comes to mind is “liberated.” I actually think Truffaut shows a greater playfulness and abandon in his follow-up film, Shoot the Piano Player, which is Godard’s favorite of Truffaut’s and one of my favorites of all time. But there’s this overall sense of Truffaut trying to find the visual language to suit Antoine’s knockabout childhood, which cannot be expressed through the more conventional strictures of screenwriting and filmmaking. The camera is restless and jittery, despite the 2:35-1 widescreen format, which I’m more inclined to associate with spectacles or more fussiness within the frame. (Godard made a joke of using it for Contempt, but that long setpiece with Michel Piccoli and Brigitte Bardot arguing in their home is as skilled a showcase of the format’s strengths as you’ll ever see this side of Lawrence of Arabia.) Spontaneity is the goal here.

Or maybe not so much spontaneity as rhythm. I suppose there’s a structure to Antoine’s life that’s not so different from any other latchkey kid who goes to school every day and comes home to an empty apartment because his parents are both working. Yet chaos reigns anyway. (Which I suppose is potentially true of all latchkey kids, in that they’re freed of adult supervision.) We’re entering into the picture in medias res, and we can certainly surmise, from the very first scene, that Antoine has been causing headaches for his parents and teachers for a long time. He doesn’t get the benefit of the doubt on the calendar pin-up that’s passed around the classroom and he doesn’t get credit for his genuine passion for Balzac because it’s easier for “Sourpuss” to dismiss him as a plagiarist. But even as a parent who would certainly be frustrated by such a wayward child, I think the film does well to suggest a core instability and lack of consistency from the grown-ups that make his rebellion understandable and his fate inevitable.

Antoine’s relationship with his parents is key both to understanding him and Truffaut’s technique here. You truly do not know, on a day-to-day or even hourly basis, what Antoine is going to get from them. In their first scene together at home, you get the impression that Antoine and his stepdad are thick as thieves while his mother has no patience for either of them. But later on, the stepdad proves tempestuous and cruel, and he’s the one who takes the extraordinary step of turning Antoine over to the police. His mother is a more complicated case: She strikes me as someone who had an unplanned pregnancy, resents her son for it, and displays a young-adult restlessness that accounts for her infidelity. At the same time, she cares about him more than her husband, I think, and it’s significant that she tries to mitigate his institutionalization by having him sent to a seaside facility. (I’ve been to that seaside town, Honfleur, and could not have been more charmed by it.)

Given how fraught Antoine’s domestic situation is, the sequence where he and his parents have a fun night out on the town is such a surprising and important stretch of the film. Though we might fairly describe Antoine’s relationship with his parents—and their relationship with each other—as unhealthy, I like how the film leaves space for moments when they’re not at cross-purposes and can have a good time together. It’s like a break in the clouds. Antoine has strawberry ice cream for the first time. They discuss the finer points of the movie Paris Belongs to Us. And all this after Antoine nearly lights the house on fire. This family isn’t wholly defined by dysfunction. They have their moments, too.

And yet, the stretch from Antoine’s incarceration to the final shot is so crushing, isn’t it? Stealing a typewriter isn’t a capital crime—and hey, he’s only caught trying to return it to his stepfather’s desk as if nothing happened—but it winds up being the final straw. Antoine cannot anticipate what might happen to him if he gets caught; it’s not really in his nature to think that far ahead anyway. But surely he could not conceive the possibility that his own stepfather would turn him over to the state and have him spend a night in an actual prison cell alongside grown-ups. The terror and sadness he feels during this stretch is so palpable, and it’s the point in the movie where we’re reminded that he’s still a child, despite his more advanced interests in Balzac and fencing typewriters.

What did you think of the lead-up to that final shot, Keith? I love what we see of the “observation center” in part because it’s still of a piece with the rest of the movie. There are some harrowing moments but also some boys-will-be-boys tomfoolery, too, like an older kid who’s caught escaping but still pleased he got to “live it up” for five days. I also like how Truffaut chooses to fill in much of Antoine’s backstory through snippets of his interview with a psychologist. There’s so much accomplished in that bit of sketchwork, and Truffaut patches it together through jumpcuts without ever cutting to the adult in the room.

Hey, I said “jumpcuts.” Another French New Wave hallmark! So let me throw the question back to you: What makes The 400 Blows a New Wave touchstone? And what do you see as its legacy and influence?

Keith: “Liberated” is a good word for the French New Wave as a whole, isn’t it? For all its key elements, jumpcuts among them, it’s easier to define the movement in the negative in some ways. It has no respect for the French “cinema of quality.” It has little interest in making movies the way they’re supposed to be made. You’ll find, as you suggest, a lot more recognizably New Wave touches in Shoot the Piano Player or Jules and Jim than you do here, but that doesn’t make it any less an act of rebellion. Who else was shooting from Parisian rooftops in 1959? It’s the sort of gesture that leads others to start thinking about which rules they can break.

That alone makes its legacy and influence massive, but I’m also pretty sure there’s a whole strand of personal and autobiographical filmmaking that wouldn’t exist, or would look radically different, were it not for The 400 Blows. It’s not that Truffaut invented the form, but the rawness and directness with which he tells a story very much taken from his own life feels radical in ways beyond the French New Wave’s stylistic breakthrough. As different as they all are, I think you can draw a direct line from The 400 Blows to, off the top of my head, The Long Day Closes, American Graffiti, and Aftersun, films that don’t really have much in common beyond being the work of filmmakers trying to use movies to explain something about their lives and the world that made them.

There’s another sort of legacy to The 400 Blows, too. Truffaut kept returning to Antoine Doinel over the years. The 1962 short “Antoine and Colette,” made for the anthology film Love at Twenty revisits him, despite the title, as a lovelorn independent 17-year-old who moves across the street from the object of his affection, as Truffaut did. (It didn’t work out for the director or his alter ego.) Three more features followed: Stolen Kisses in 1968, Bed and Board in 1970, and Love on the Run in 1979. I rank Stolen Kisses, in which Doinel bungles his way through love and early attempts at a career, nearly as high as The 400 Blows. (It also inspired one of my all-time favorite posters.) Bed and Board isn’t quite at the same level and Love on the Run, which is more or less the cinematic equivalent of a sitcom clip show episode, is kind of a bummer way to end Doinel’s story. I wish Truffaut had lived longer for many reasons, the possibility of following Doinel into middle age and beyond among them. But, uneven as the series might be, I love that it exists and that we get to see Doinel grow up before our eyes. Richard Linklater was obviously taking notes. (And, hey, there’s another piece of the legacy for you.)

What’s our next stop? I’m glad you asked. We’re returning to the United States for a high-placing new addition to the 2022 list: Barbara Loden’s Wanda.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

#67 (tie): Metropolis

#67 (tie): La Jetée

#66: Touki Bouki

#63 (tie): The Third Man

#63 (tie): Goodfellas

#63 (tie): Casablanca

#60 (tie): Moonlight

#60 (tie): La Dolce Vita

#60 (tie): Daughters of the Dust

#59: Sans Soleil

#54 (tie): The Apartment

#54 (tie): Battleship Potemkin

#54 (tie): Blade Runner

#54 (tie): Sherlock Jr.

#52 (tie): Contempt

#52 (tie): Ali: Fear Eats the Soul

#50 (tie): The Piano

Discussion